Rudolf Steiners "Philosophy of Freedom" as the Foundation of Logic of Beholding Thinking, Religion of the Thinking Will, Organon of the New Cultural Epoch

Volume 2

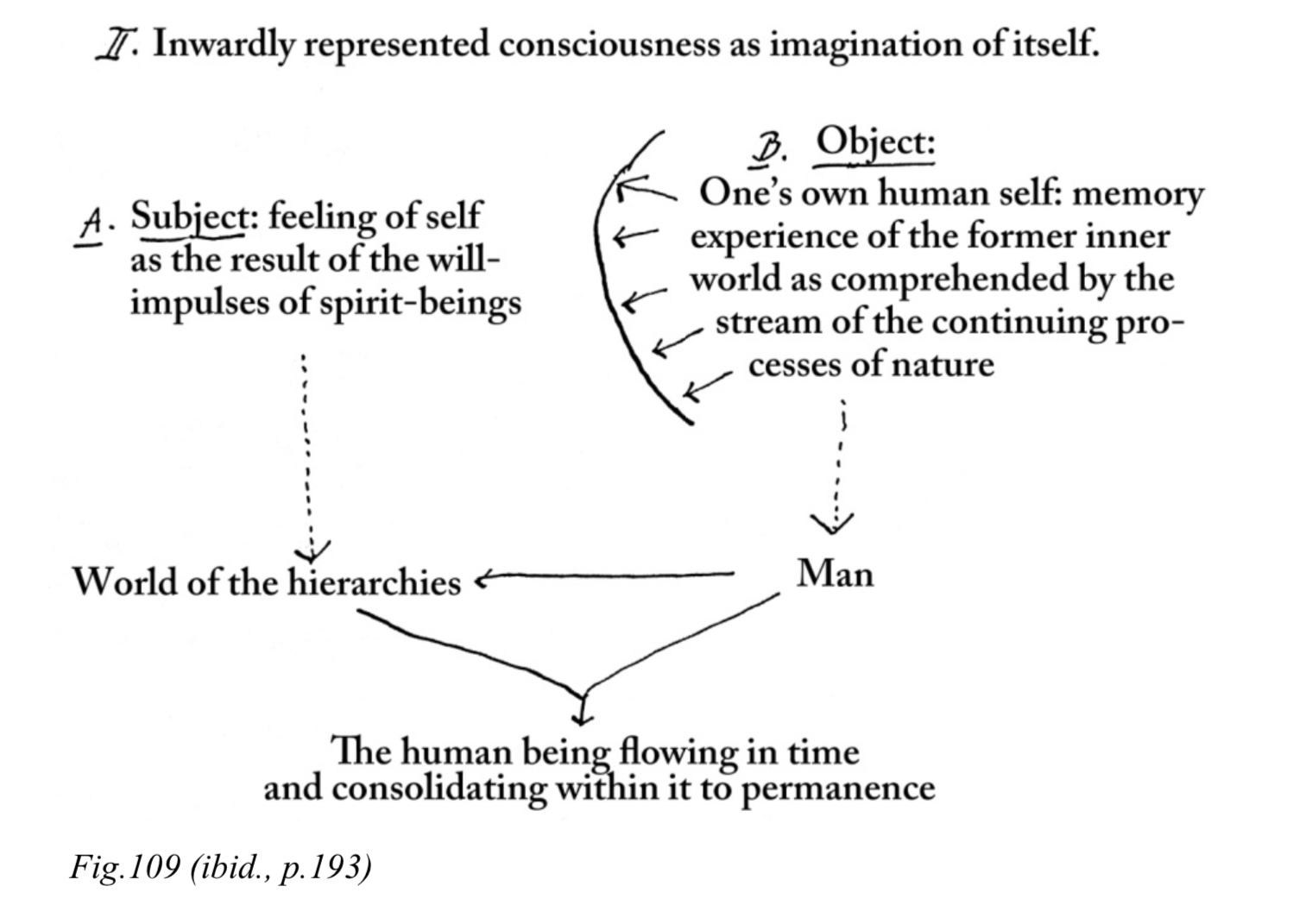

IX Memory Picturing

1. The

‘Ur’-Phenomenon of Man’s Evolution to Spirit

2. A Leap

across the Abyss of Nothingness

3. The

Threefold Bodily Nature and Memory

4. The

Phenomenon of the Human Being

5. Memories

outside the Physical Body

'Die

Philosophie der Freiheit'

Chapter 7 – Are

there Limits to Knowledge?

IX Memory Picturing

1. The ‘Ur’-Phenomenon of Man’s Evolution to

Spirit

We stated earlier, that all efforts of the human being to get to know Anthroposophy in a way that is in keeping with its essential nature, are doomed to failure if they have the character of the mere understanding. When this is the case, it is impossible to find a relation to its qualitative aspect. It is absolutely necessary, not only to grasp, but to experience the fact that Anthroposophically-oriented spiritual science, although it embodies a coherent system and despite its colossal range, has been left incomplete in all its parts by Rudolf Steiner. Therein lies its methodological peculiarity, which stems from the cognitive principles that were customary in the great Mysteries.

Out of an ocean of unbounded cosmic wisdom Rudolf Steiner created a kind of ‘conduit’ into the realm of human cognition. As it streams through this ‘conduit’ into the thinking consciousness of the human being, irrigating and enlivening it, this wisdom has the impulse to return to itself and to carry the human being with it on its waves, and in this way to lead him, as a matured individuality, back into the ocean of the spirit which he left behind on his entry into earthly being.

In this reciprocal relation between man and world, both are incomplete. For, the human being proceeded from the spirit as an integral part of it and, therefore, both retained the urge to restore the lost unity, thus providing development with its impulses in its passage through the multiplicity of forms. In this sense, every form whatever of cognition is merely a phase of transition between the forms of the being of forces in the free play of creative activity. As these forces ‘flow down into’ the sphere of sensory being, they experience the tendency to rigidify in forms, and one of these is the ‘I’-consciousness that thinks according to the laws of logic. The formal nature of logic sets limits to it, conditioning thereby the abstract character of its form. To overcome this form, the ‘I’-consciousness needs to develop within itself a new kind of ‘capacity to flow’, which is able to metamorphose both itself and the form of logic.

‘Capacity to flow’, evolution and metamorphosis are not synonymous, yet in the case in question they are related. Through operating with them as with attributes of consciousness, the teachers in the ancient Mysteries imbued cognition with a playful character and clothed it in the form of riddles. Thus imagery, phantasy and also elements of spiritual freedom entered into the cognitive process – that is, everything that actualizes the will in the thinking. Something similar is true of the Anthroposophical method of cognition. The huge multiplicity of facts contained in Anthroposophy can only be handled with difficulty by intellectual means such as classification, formalization, schematization etc. In reality they are all riddles or components of riddles. Like the mythical Sphinx, Anthroposophy comes towards us in the shape of a mighty system of riddles. It is in their solution that the process of cognition consists, which is at the same time a process of the conscious reunion of the cognizing subject with his many-membered being and with the being of the universe.

Not only outside Anthroposophy, but – strange as this may sound – not infrequently among its adherents, one meets people with a nominalist way of thinking who reproach Rudolf Steiner for “inconsistency”, “self-contradiction”, “errors of judgement” etc. They are unable to grasp the “non-Euclidian” character of the relations between the ideas of spiritual science. In these circumstances, what can they do when they read in a lecture of Rudolf Steiner that, for example, the soul of the human being is formed by memories (cf. GA 232, 24.11.1923), in another, that the “preserver of the memory” is the ether-body (GA 266/3, p.248) and, finally, in a third, that our ‘I’ is woven out of our memories? Is then, so they have to ask themselves, the soul identical with the ether-body, and this with the ‘I’?

No, anyone who wishes to know spiritual science must at the same time learn to love both the free play of concepts and soul-forces, and a strict development and organizing of concepts – but, with regard to himself, the movement from the conditioned to the free, to free self-conditioning (or ‘conditioned-ness’). Where this is the case, the process of cognition of Anthroposophy will be organized in consonance with its methodology. We will be endeavouring to work in this spirit as we complete our study of the triad which we arrived at in Fig. 56 in our discussion of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’.

It is out of the totality of the three worlds that there germinates and develops the human individuality, which is subject to the conditions of sensory being. Two of them he finds before him as given elements: one outside him and one within. These are the world of percepts and the world of concepts. We need only use our sense-organs, and experience of the percepts is impressed into us. From a certain age onwards the percepts begin to call forth in us the concepts, and then we move on to the forming of inner representations – the third world. These penetrate into the depths of our being and unite with the sheaths. From then on, a part of them can be drawn out from there thanks to the power of memory.

Through their manifold activity, these three worlds form the lower ‘I’. This emerges as our own strength (force) of consciousness, of spirit, which has the capacity to draw together into a unity within us the workings of the three worlds. The lower ‘I’ shows itself to be identical with the scope of our memories. “In everyday existence,” says Rudolf Steiner, “the human being is the product of his memories” (GA 115, 16.12.1911). The world of percepts and the world of concepts bring to us the streams of experiences, and the way in which our experiences become memories determines the forming of the triune soul. Pathological irregularities in the memory becloud the ‘I’.

Thus, the dynamic totality of four components – percepts, concepts, memories and ‘I’ – constitute the phenomenon of the conscious, earthly human being. Of these, the most important is the memory, the remembering of oneself as a quality of the ‘I’. Before we investigate this phenomenon further, we must decide whether we conceive of it as a single object of cognition (in which case, we risk treading the path of natural- scientific positivism), or as a constituent part of a kind of dialectical tri-unity, or finally as an element of the seven-membered metamorphosis, which corresponds to the evolutionist principle of the spiritual- scientific method. In the latter case, the first step in a methodological organizing of the research is a highlighting of the question as to the principle of self-movement of the phenomenon ‘I’.

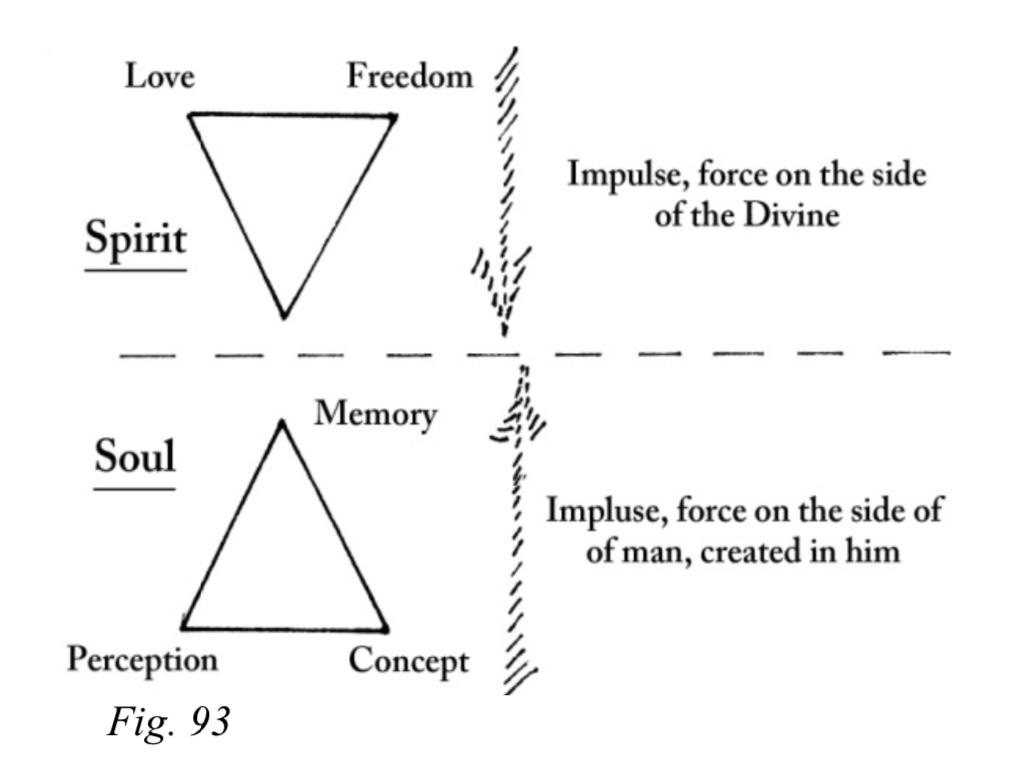

The appearance of the lower ‘I’ within the tri-unity of percept, concept and self-remembering shows signs, unquestionably, of having been “induced”. It is the counter-pole to another unity, and therefore the striving towards the higher is immanent to it. In the triangle of forces which we have arrived at, the ‘I’ appears as an impulse that remains, in its entirety, on the side of the human being. The counter-pole that corresponds to this reveals itself on the side of the Divine. The dialectical movement within the ‘I’ is conditioned by the similarity, as an inherent principle, between the lower and its higher counter-pole. For this reason the higher, which corresponds to the earthly phenomenon of man, is also triune. Its three structural components draw the higher ‘I’ of the human being into a unity.

At this point it is worth referring again to the symbol of the Holy Grail, which we already spoke of in Ch. VIII, as this corresponds to that reciprocal relationship which we are about to discuss. The symbol expresses the many-sided relation of man to God, which is anchored, on an evolutionary level, in the constitution of the human astral body. For this reason, epistemological research must necessarily assume an ontological character.

The higher tri-unity we are now seeking, which reveals itself to the higher ‘I’, can have different constituent parts. For example, it can be the tri-unity of Manas, Buddhi and Atma. If we seek a relationship to it of the lower triad which we are studying, we need to acquaint ourselves with a whole series of intermediary stages. It would therefore be advisable to find a higher triad that corresponds more directly to the lower, but above all contains within its structure at least one element of the lower triad. We find the solution in a lecture given by Rudolf Steiner in 1923. He says there: “This is what arises as a threefold force of the soul in its innermost depths: freedom, the life of memory, the power of love. Freedom – the primordial inner form of the etheric or body of formative forces. The power of memory – the inwardly arising, dream- forming power of the astral body. Love – the inwardly arising power of love, which leads the human being to surrender in devotion to the outer world (this power is rooted in the ‘I’ – G.A.B.). Through the fact that the human soul can partake in this threefold force, it imbues itself with the spiritual life. For, this threefold permeation with the feeling of freedom, with the power of memory, through which we hold together past and present, with the power of love through which we are able to devote ourselves to the outer world, through the possession of these three forces of the soul, this soul of ours is imbued with spirit. ...the human being bears the spirit within him. And whoever cannot grasp in this way this threefold inner permeation of the soul, cannot understand how the soul of the human being contains the spirit” (GA 225, 22.7.1923).

One could italicize this communication of Rudolf Steiner for greater emphasis, as it makes possible for us an important discovery in the sphere between consciousness and being.

The higher or, rather,

upper tri-unity of which Rudolf Steiner speaks

applies to the soul-structure of the human

being, on whatever level or within whatever

structure we view it. In the context of the task

we have set, we will bring it into connection

with the tri-unity which we are investigating.

Then we arrive at a system that has the form

recognizable in Fig.93.

In this situation the

soul-spiritual being of man can be compared to a

dipole in which, through a force working from

above (our ether and astral bodies possess the

higher consciousness of Buddhi and Manas), the

structure working below in the

earthly-individual element is in a certain way

‘induced’. And the latter, as it unfolds, begins

to exert an influence on the upper tri-unity, on

the character of its impulse.

Rudolf Steiner points to the connection of the

process of gaining freedom with the ether-body,

but the ‘nuance’ of our discussion is of a

different kind. Our aim is to highlight the

symbol of the human astral body, on whose

individualized activity an understanding of the

idea of freedom depends. It possesses its

‘ur’-phenomenon, expressed in the symbol of the

Grail, which shows its macro and microcosmic

nature. In Fig.93 this is represented through

the upper and the lower triangle. In them stand,

in polar opposition to one another as the

principles of their unity, the two ‘I’s, which

are the precondition for the development, the

individualizing, of the astral body. This comes

to expression in the steadily increasing

immanence of the upper triangle in the lower.

The connecting link between the two triangles is

memory. This is born in the lower triangle and reborn

in the

upper. Overall, we have to do, if we follow our

methodology, with a perfect sevenfoldness of

elements, which form the lemniscate of

development, thanks to which the lower ‘I’ is

gradually transformed into the higher ‘I’. We

merely have to resolve the question: What is it,

concretely, that effects the transformation in

this lemniscate? Which ‘I’?

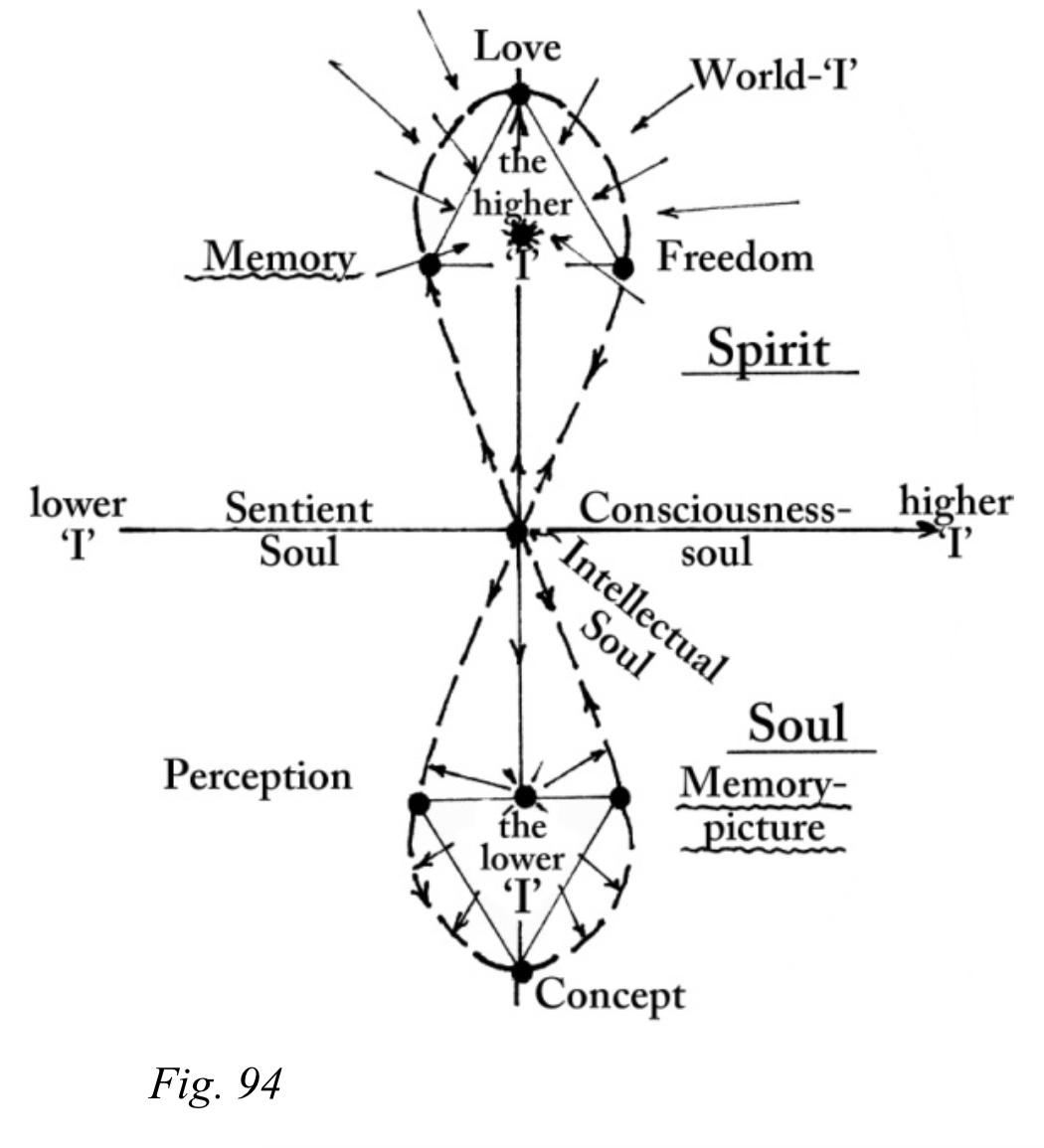

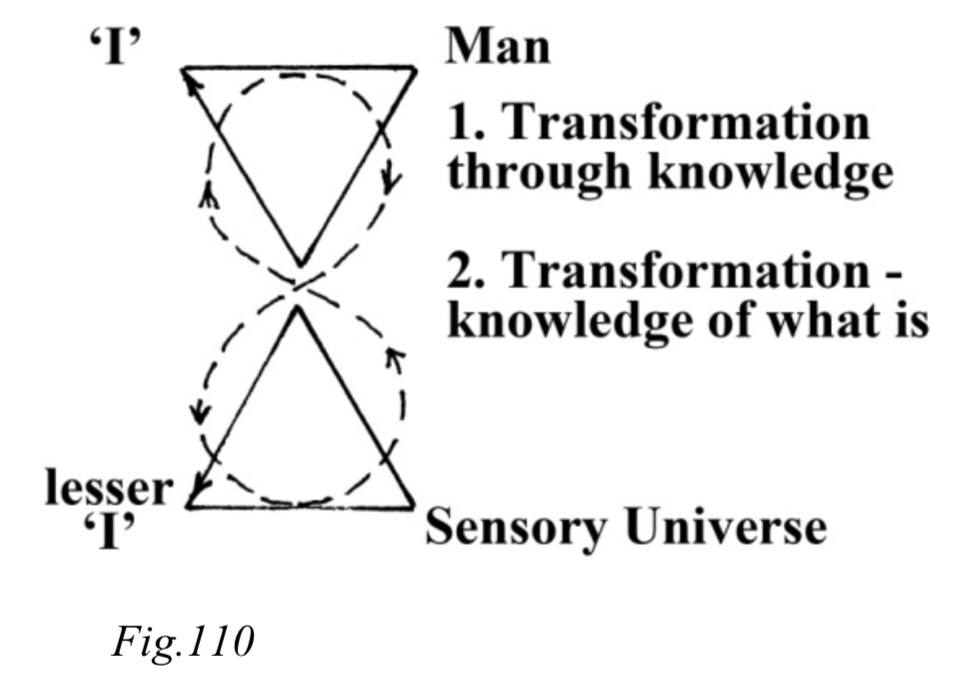

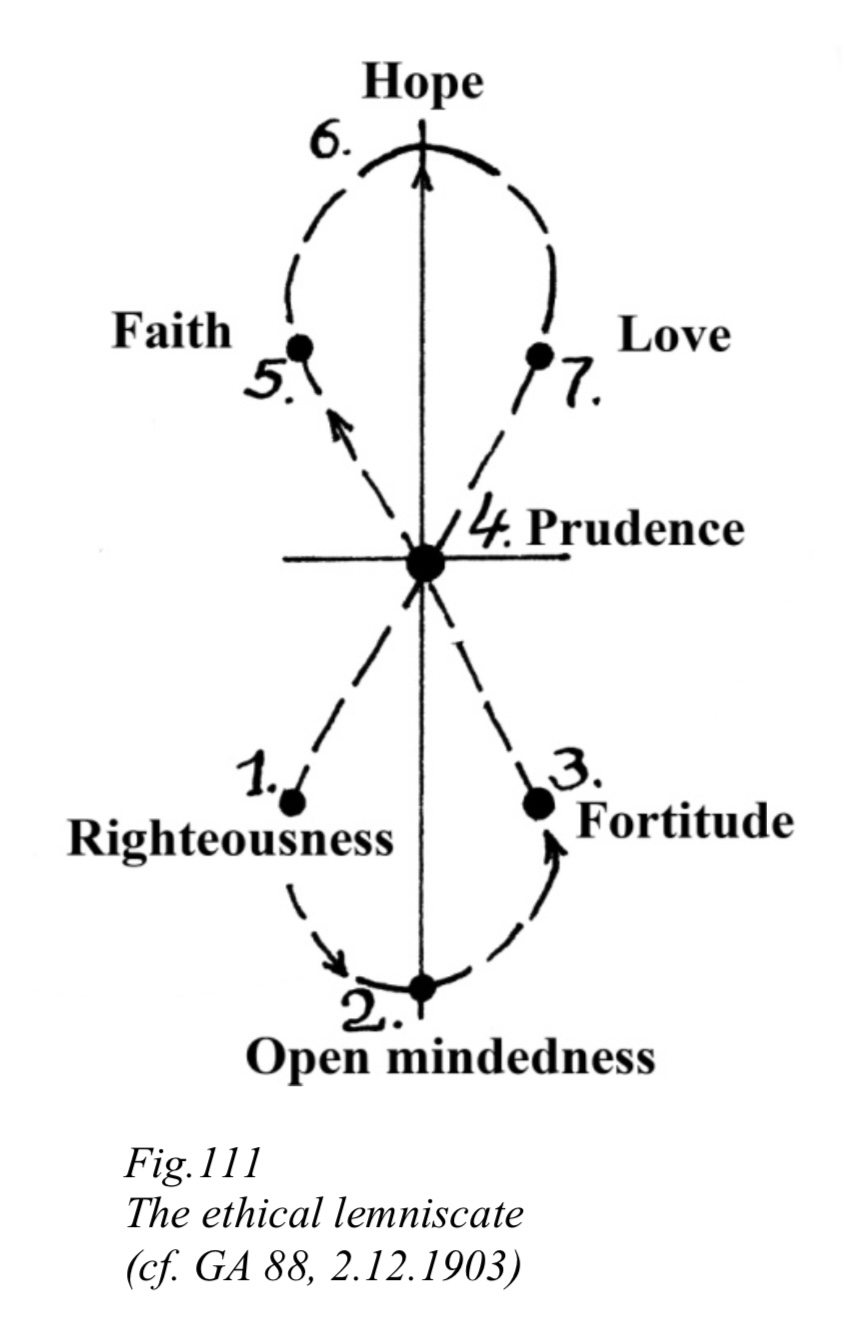

In our seven-membered metamorphosis of thinking, element 4 is the centre (the point) of transformation of the lower to the higher. It is important, not so much for its content, but because of its ability to perform certain actions. This is also the field of force in which the triune soul reveals itself and develops. Different human beings possess the capacity of ‘beholding’ in differing degrees. Here, everything depends upon the soul-member in which the person mainly functions. In individual development he is moving simultaneously on two axes: the vertical in a lemniscatory movement, and the horizontal in space and time. Along the second axis the human being, in the process of education, of the life of culture etc., involutes the triune soul. By virtue of the ‘I’ strengthening within it – which is on the path from the lower to the higher ‘I’ – he brings about in himself an individual evolution. Its foundation stone is laid through the activity of the lower ‘I’, which reaches through consciously into the three worlds – described above – of the individual life of the human being (Fig. 94). In the transition into the higher sphere, an inwardizing takes place of the activity of the ‘I’, which has gained higher qualities through emanations of the World-‘I’. Thus we have arrived at the best possible lemniscate of individual development, in which its principle and its process are revealed with special clarity. One can regard it as the ‘ur’-phenomenon of man’s evolution to the spirit. As opposed to the gnoseological lemniscate of the thought-cycle, this lemniscate has an ontological character, which will now be developed and discussed in further depth.

2. A Leap across the Abyss of Nothingness

In the lower loop of the lemniscate shown in Fig.94 the everyday ‘I’ of the human being, which grows in strength thanks to the experience of perceptions and also of thinking, gradually achieves mastery over these, creating out of them the basis for its own being – in the form of inner representations and memory pictures. The subject receives the initial impulse for this individual activity from the sphere of its supra- individual, higher nature – from the upper loop of the lemniscate – which has formed in the course of the preceding evolution, of the experience of many reincarnations. To begin with, it works unconsciously, whereby to a significant degree it is mediated by the cultural and social environment.

In the upper loop there arises, as the driving force of the soul-spiritual life of the subject, the higher ‘I’. Its genesis is complicated and many-faceted. To reveal its content our best approach will be to deal with the question again and again in relation to the different aspects of our discussions. From the statements of Rudolf Steiner we know that the human race (or species) was endowed by the spirits of Form, in the Earth aeon, with a single and universal ‘I’ (cf. Fig.35). Thanks to this, the three bodies of man are formed from the beginning of the aeon in a different way than in the animal kingdom. As a counterweight to the universal ‘I’ the human being has developed, in the genesis of the tri-une soul, the personal, lower ‘I’. Their reciprocal relation is expressed in the Fichtean ‘I = not-I’. Their equality is not a constant; this is a potential equality; in it is gradually formed the higher, individual ‘I’, in which body, soul and spirit of the human being achieve a conscious unity. In the equality of I = ‘I’, development assumes the character of gradual mastery of the higher stages of consciousness which surpass, at a certain level, even the consciousness of the spirits of Form. In the primal source of all the ‘I’s in the world there holds sway the Divine World-‘I’, which is conditioned by nothing and conditions all other things. It is free in all eternity; leading the human being to Itself, It leads him to freedom. Its centripetal tendency is at the opposite pole to the egocentrism of the lower ‘I’. For this reason there arises, in the transition from the lower to the upper loop of the lemniscate – shown in Fig.94 – but also in the lemniscate of thinking, the necessity to cancel and set aside (aufheben) the lower ‘I’. Ontologically, this takes place in the transition from memories of one to another kind, which is accompanied by the development of the triune soul.

The cancelling and setting aside of the ‘I’ requires a high degree of development of the ‘I’-consciousness. This can be acquired in the individual experience of learning how to control the life of thoughts, feelings and expressions of will. This is shown in the fact that in the consciousness-soul love for the deed becomes the motive and the spring of action. This love for the deed germinates in the intellectual soul by way of the development of love for the object of cognition, which finds its expression in the ability to identify with it. In the process of this cognition and activity the higher love enters the human soul and transforms the ego-centredness of intellectualism, which manifests in dialectic, into the indirect egoism of ‘beholding’*, which embraces the real-ideal (not abstract, but having the nature of essential being) content (existence) of the object. Such a process (or mode) of cognition (of action) cannot but contain within itself a moral purpose. The human being forgets himself in the cognized object and thus cancels and preserves the earthly memory within him, in order to attain to a ‘beholding’ of its content in supersensible reality.

* It is indirect, because

the phenomenon of the ‘I’ itself is not

cancelled and set aside (aufgehoben).

________

As man’s evolution to the spirit begins already in the sentient-soul, it is bound up with the experience of perception. It is thanks to this, that the human being receives his first experience of the ‘I’. The first impulses to freedom enter this ‘I’ from above, but as this soul is weak and imperfect the idea of freedom it holds to is invariably a mistaken one. Freedom is confused with arbitrariness, political freedom is demanded instead of equality and economic freedom is sought, which can only lead to the enslavement of human beings, etc. In the sentient-soul the freedom impulse is itself strictly determined by the nature of the perceptions, especially of the lower senses – of life, movement, balance and touch. Only gradually, thanks to the development of the higher soul-members, does the human being learn to perceive in an entirely selfless way: to ‘behold’. Then he comes into immediate contact with freedom.

As in the lower triangle of the lemniscate (cf. Figs.93, 94) all the elements are drawn into a unity, the changes in the character of perception and thinking have their effect on the development of the memories. In the present case, this triad is also dialectical. The antithesis between perceiving and thinking attains to a synthesis in the memory-representation which forms the content of the ‘I’. Is this content form or being (life)? In the lower triad we have unquestionably to do only with the form – void of substance – of the existence of the ‘I’. This contradicts the nature of the ‘I’ as such, but if it could not be cancelled and set aside (aufgehoben) the lower ‘I’ would attain real being, and the path to freedom would be closed to us.

All the processes in the lower loop of the lemniscate must have a conceptual-pictorial-reflective character (the concept, too, is picture). “In this fact,” says Rudolf Steiner in ‘Anthroposphical Leading Thoughts’, “that the human being in his momentary act of inner representation is not within being, but only in a mirror-reflection of being, in picture-being, lies the possibility of the unfolding of freedom. All being within consciousness is something that compels. The picture alone cannot compel” (GA 26, p.216).

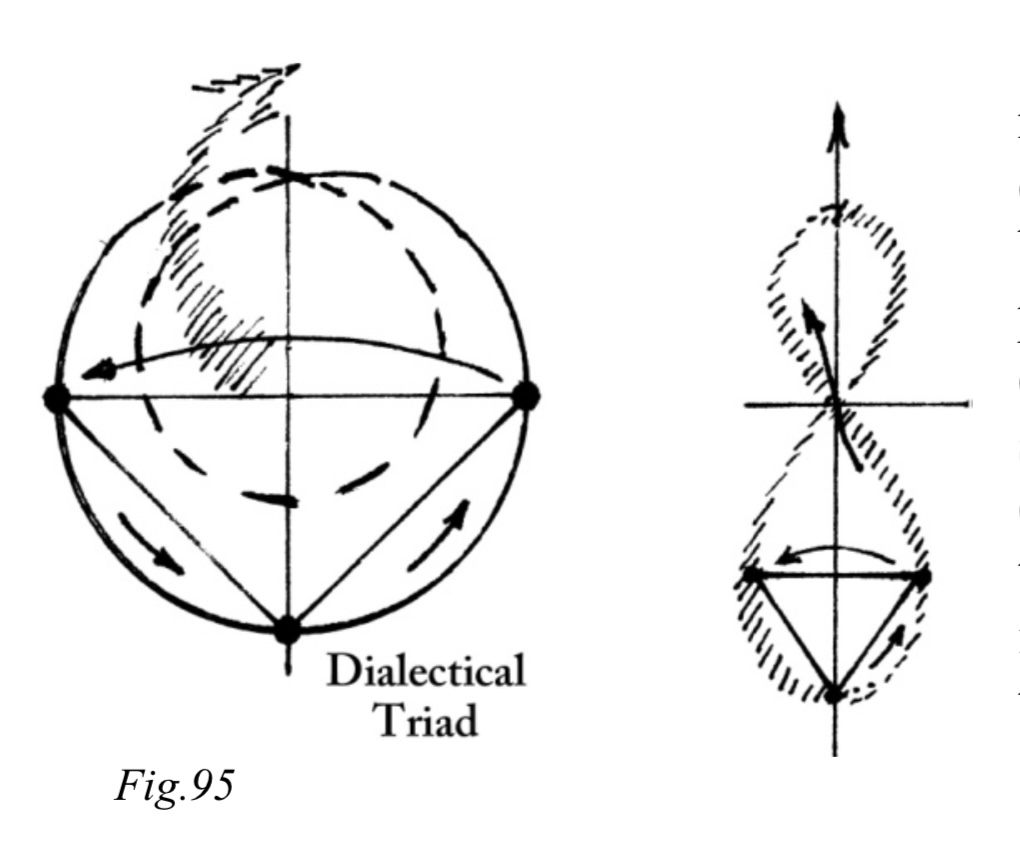

Through ascending, with

the help of conceptual-pictorial-reflective

thinking, to the consciousness-soul – its

pictorial nature amounts in this case to an

experiencing (not thinking-through) of the

processes of its metamorphoses – the human being

is freed within himself from any kind of natural

or naturally conditioned existence and then

makes the leap across the abyss of nothingness,

of not-being – not in the Hegelian, but in the

occult sense – and now finds himself in the

world where consciousness has the character of

essential being. This leap signifies a radical

change in the direction of development, a

certain “bouncing off” from the boundary of

being, which has the form of a sudden “leaping

forth” of the upper loop of the lemniscate from

the lower, into which its gaze was always

turned, as into man’s unconscious being.

(Fig.95)

The human being moves round within the closed circle of the dialectical triads, but on an unconscious (supersensible) level the processes within him correspond always to the upper (inside the lower) loop of the single lemniscate. This is one of the meanings of the words: “The kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17, 21). By bringing

about within himself an empty, but waking consciousness the human being turns, as it were in one stroke, the inner loop “outwards” into the supersensible world, and emerges there as a self-conscious individuality. One question remains, however: What maintains him during this leap?

If the processes of perception and thinking were to produce lasting forms within the human being, he would lose himself in them; in them as the object he would lose himself as subject. For this reason, the process of forgetting helps the subject to maintain itself. In fact, the system of the sense-organs, for the human being who has descended from the spirit into incarnation, is the outer world. The human being enters it gradually with his soul-spiritual being which advances from one incarnation to the next. Thus, as Rudolf Steiner explains, “the colour... together with the eye, does not ‘belong’ to the human being; the eye together with the colour belongs to the world. During his earthly life the human being does not let the earthly surroundings stream into him – he grows outwards into this outer world between birth and death” (GA 26, p.232 f.).

Also in his thinking organization the human being does not belong to himself, but to the world; the world-thoughts hold sway in him through his thought-organization, with which he “grows outwards into world-thinking”. “With respect both to the senses organization and to the thinking system the human being is world. The world builds itself into him. Thus, in sense-perception and in thinking he is not himself, but there he is world-content” (ibid. p.233 f.).

And, finally, in the unfolding of the memory in the human being, Divine-spiritual being is at work. In the lower ‘I’, however, the memories arise in us only in picture form and void of substance. But they are active within us in connection with the life-forces: the ‘I’ needs only to become somewhat weaker and we become a plaything in their hands; they can even take on a compulsive character through returning again and again and stirring up the emotional sphere.

The human being, surrounded only by the world of pictures, nevertheless finds the strength to create out of them the forms of his memories. This force proceeds from the upper loop of the lemniscate shown in Fig.94. From out of the sphere of the higher ‘I’ there stream into us impulses and forces which condition the development of our self-consciousness, so long as this has not attained the power to condition itself.

Indeed, the processes of perception and thinking represent within us a kind of non-material “painting activity” of the soul, which is unable to leave behind in us lasting traces, but parallel to them a further process occurs “where the forces of growth, the life-impulses are at work”. “In this part of the soul-life there is imprinted through perception, not a merely transitory image, but a lasting, real image. This, the human being can bear (i.e. not lose himself in it – G.A.B), as it is connected with the being of man as world-content (i.e. that which comes from the up- per part of the lemniscate – G.A.B.). As this takes place, he can lose himself just as little as he loses himself when he grows, is nourished, without his full consciousness” (ibid., p.214).

It is out of this parallel, unconscious process that we draw our memories as a content of our individual life. But they, too, must of necessity retain, intermittently, an ephemeral character, remain pictures – until we are able to endow them with the character of imaginations. Then the memories in us will become the faculty of higher ‘beholding’. This is what “awaits” us on the other side of the abyss of non-being. Rudolf Steiner describes as follows what happens as the transition takes place: “What we experience in our consciousness as inner picturing has originated from the Cosmos. Vis-à-vis the Cosmos, the human being plunges into non-being. In inner picturing he frees himself from all the forces of the Cosmos. He paints the Cosmos, outside which he is standing. If only this were the case, freedom would light up in the human being for a cosmic moment; but in the same instant the human being would dissolve. – But through the fact that in inner picturing the human being becomes freed from the Cosmos, he is nevertheless linked together in his unconscious soul-life with his previous earthly lives and lives between death and a new birth. As a conscious being, man is within picture-existence, and with his unconscious he maintains himself in spiritual reality. While he experiences freedom in the present ‘I’ (i.e. the lesser – G.A.B.), his past ‘I’ (i.e. the higher – G.A.B.) maintains him in the realm of being. With regard to being, man is in his inner picturing given up entirely to what he has become through the Cosmic and earthly past” (ibid., p.216 f.). In this, he is bound up in his lower being with the guiding higher Cosmic forces, which represent world-life and the Cosmic Intelligence. It is they, who preserve the human being when, striving towards freedom, he makes the leap through emptied consciousness over the Abyss of non-being. “Michael’s working and the Christ impulse make the leap possible,” Rudolf Steiner concludes (ibid., p.217). They help the human being to transform the “nothingness” of the pictures into the “All” of the free imaginations.

3. The Threefold Bodily Nature and Memory

These two ‘I’s, of which Rudolf Steiner speaks in the statement quoted above, we have shown in Fig.94 on the axis which separates the lower from the upper loop of the lemniscate. The higher ‘I’ is closely connected on this axis with development in time. It is present in the upper loop of the lemniscate in the one-dimensionality (point-nature) of the spiritual space, which the time of the (lesser) ‘I’ becomes in individual experience. The “past” ‘I’ is also the “future” ‘I’, into which we bear the fruits of the development of the lower ‘I’. The ‘I’ that illumines us from above is potentially identical with the Divine ‘I’; they are separated by a series of stages or, rather, forms of the existence of consciousness.

Through the Divine ‘I’ was revealed the absolutely unconditioned freedom of will through which our evolutionary cycle was posited. On its entry into the world of otherness-of-being this will originally became the absolutely conditioning principle. Thanks to it, we have acquired our bodily nature. It works, unconscious to us, in our limb-metabolism nature, in the process of growth, nourishment, reproduction etc. – that is, it constitutes the seven life-processes. One stage higher, the same will works in the forming of the system of the twelve sense-organs and, finally, the processes of perception and thinking. At this last stage the human being reaches a boundary above which the conditions arise for a free setting of goals. On this level of individual development (it corresponds to the upper loop of the lemniscate) the human being turns himself in evolution, figuratively speaking, with his gaze directed backwards. There takes place, in a certain sense, a repetition of the evolutionary process which once formed the transition from the Lemurian to the Atlantean period (see Fig.89) – but now on a higher level. – It becomes the task of the human being to absorb into his onto- genetic being, consciously, the soul-spiritual phylogenesis of humanity. For this reason the power of memory begins to play a decisive role at this stage of development.

We have already pointed out that in empirical time, on the etheric-physical level, the world-process moves from the past into the future, through a union of the three world-forces – substance, life and form. On the astral level the movement of time flows in the opposite direction. Every moment of the encounter of the two movements is characterized by the ‘I’-phenomenon. One of them is also the (lower) ‘I’ of man, and therefore everything in it is a dynamic process of becoming and transformation. The activity of transformation begins in the lower ‘I’ with the conducting of the will into the thinking. It is upon the will that the ‘height’ of the thinking depends in relation to the stream of development, and upon the ‘height’ depends the depth of conscious penetration into the future (exclusively in ‘beholding’) and into the past (on the level of essential being).

Manifold preconditions exist in every human being for a maturation of this kind. On a subconscious level they are created in the preceding phase of development. At any given moment of the present we bear the entire past within us. Even the metabolism preserves within it the memory of man’s evolutionary past. In the animals and plants this process is different because their past and also the memory of it are different. The human being also retains the memory of the entire cultural and historical past of humanity, in which his personal biography embraces the totality of the reincarnations he has already completed. A memory of this kind is bound up with the process of individualization of the astral body and also with its activity within the other two bodies.

Among the numerous ways of imagining the astral body, says Rudolf Steiner, there is the one that sees it as a reader of the occult script which is written, as on a tablet, onto the ether body by the entire world process gone through by the human being. Therefore “the ether body of the human being is indeed a true copier in miniature of the entire Cosmos. There is nothing in the Cosmos that does not imprint itself as an imaginative picture in the human ether body and, if one wishes to use the expression, is reflected as in a mirror” (GA 156, 12.12.1914).

The astral body of every human being is macrocosmic in nature. The primal source of its activity is still in the first globe, in the upper Devachan, into which we will only ascend consciously in the future. On this spiritual height the astral body stands in immediate, concrete relation to the revelation of the hypostasis of the Holy Spirit, which creates within us the ‘I’-consciousness. The human being incarnates on earth in such a way that his astral body – unconsciously, of course – is connected with the spiritual being of the fixed stars and with the astral aura of the Solar system. After his death, the human being unites with this astral body, but so long as he is living on the earth his astral body forms a small loop within the large loop of our macrocosmic astral body (as shown on the left in Fig.95). The inwardized (small), subjectivized as- tral body is especially influenced by rays coming, so Rudolf Steiner tells us, from the Zodiacal sphere of Aries. It tries to hold these rays fast in a particular form and confine them within a beautiful contour. Through forces proceeding from the constellation of Libra, movements arise in the astral body, which enable it to open itself up to its surroundings. In all, the earthly astral body receives from the Zodiac twelve kinds of movement. Also from the planets movements enter it, but they have a more inward character; there are seven of these (ibid.).

Through the totality of the influences streaming in from Zodiac signs and planets, particular ‘habits’ develop in the astral body. For example, they determine what lives in speech as vowels and consonants. With the help of its 19 ‘habits’ the astral body reads the ‘inscriptions’ in the ether body and inscribes new ones into it. Suppose, for example, that we have met someone. The astral body builds up his image with the help of the 19 habits, creates the inner representation of an impression it has received, and of which we become conscious. It does, of course, fade within us quickly, but the astral body engraves it into the ether body, from which it can later be retrieved – read – again.

An important role in the act of remembering is also played by the physical body. Without it we would have no relation to the ether body as a preserver of memory. When we remember, or think, the astral body makes imprints in the ether body, and this in the physical body. The latter works as a kind of instrument for registering what we wish to impress into our memory. But in no way is it, itself, the organ of memory. Astral and ether body have to reach through to their imprints in order to remember them. Here, of course, a certain impulse must also come from the physical body. But one should not imagine that this process is like a ‘taking down’ from the ‘memory shelf’ in the brain, of the ‘memory chits’ one has previously placed there. In order to play a part in the process of memory the physical body also needs to have developed habits, and this happens if we repeat the observations we have made and, by giving greater nuance to our feelings, deepen the impression made on us by what we have observed.

In the world, everything is pervaded with movement and rhythm. When these change in the human sheaths, and in their substances, his consciousness, his existence, changes, the forms of their expression change. The astral body envelops us like a cloud in which passions, desires, instincts of all kinds are in movement. If one gives them too much freedom, this leads to chaos in the memories. Chance influences from outside then begin to conjure them forth from us. We become the plaything of certain memories. For this reason, thinking must bring order into the astral body, generate within it stable vibrations and bring these gradually, on a higher level, into conscious relation with the cosmic vibrations.*

* The ‘Rückschau’

exercise, for example, aims to achieve this.

______

In the ether body the memories change that part of it which is freed from activity in the life-processes and serves consciousness. In those kingdoms of nature where there is no free part of this kind, there is also no memory.

In the physical body the forming of memory-representations and the forgetting of them goes hand in hand with material deposits and their dissolution.

The ‘I’ leads everything that takes place in the three bodies to a unity through working in a flexible interplay of the two processes – imprinting in the memory, and forgetting. This happens in the following way. Thanks to the astral body the impressions aroused in us by outer objects become conscious. But the working of the astral body alone here is not enough. In the process of perception it is necessary to move with one’s everyday ‘I’ into the astral body and change its character by way of the judgement; then the character of the perception also changes. If this process does not occur, the sense-perceptions are dulled, and with them the ‘I’-consciousness also. Through the combined activity of the ‘I’ and the astral body the percept becomes inner representation. Initially, this has a pictorial character that reminds one of Imagination, but then it imprints itself into the ether and physical bodies. These ‘imprints’ are described by Rudolf Steiner as something like fine, shadowy ‘ghosts’, which have the form of our head and of what attaches itself to this from below – the system of the spinal marrow. There are as many “ghosts” clustered together and rooted within us, as we have memories, but they bear no resemblance at all to the things we remember. The physical body reveals, by virtue of its habits, certain signs which repeat the image of the head and of what is below it. As the astral body reads these, it metamorphoses them radically, and ‘deciphers’ them. And just as in the reading of a book, one must undertake this deciphering anew, again and again, if one is to remember anything. The light-ether is bound up with the imprints of the memories, which appear in the ether-body.

Thus, the process of memory-formation always has a sensible-supersensible character. In the power of memory we feel, so Rudolf Steiner tells us, our affinity with all the forces of the Cosmos that work creatively in development. Whether we are observing trees, mountains, clouds, stars, and the way they all come into being and change their forms, or whether we try to behold the form-building forces in the world – there always arises something in the soul, that has an affinity to what is happening outside. These are the forces of memory. They are cosmic reflections of all that is working, weaving, undergoing meta- morphosis in the outer world (cf. GA 335, 22.7.1923).

The percept arises in us because the ‘I’ (here, both ‘I’s are working, the lower and the higher) and the astral body receive, not just an external impression, but a revelation of the things. If no imprinting in the memory takes place, the process ends with a (conceptual) conclusion in which the everyday ‘I’ is at work. But the part of the perception that remains in the subconscious lives on within us, is mirror-reflected in the instrument of the sense-organs, in its nerves, reaches down into the depths of our physical and ether bodies. The ‘I’, which is involved in perception, lends extra movement to the blood (working upon it via the nerve, with the help of the astral body) and thereby stimulates the ether-body. In this, various currents arise. Together with the bloodstream they move from the heart to the head. Rudolf Steiner remarks that Aristotle and Descartes still knew of this stream.

* * *

If we wish to understand this process more concretely, it should be pointed out that in perception we enter into contact with the entire etheric world which, in this case, comes towards us as the external world. As it works upon us, it brings into vibration all the four ethers of which our etheric body consists. The process in them unfolds parallel to what happens in the astral body and ‘I’ when we are perceiving with the physical sense-organ. Suppose we see a human being. The impression made on us arouses vibrations in, for example, our light-ether (whereby the other ethers also vibrate). The thoughts that are aroused in us by the perception also come to expression in the inner light movements. There arise in us the image of the percept and also the inner representational picture. When the meeting is repeated, the light-body makes the same movements as it did before, and we remember the person in question. To remember the inner movements of one’s own light-body (ether), which are brought about by the external ether, means to remember.

All that we have spoken of here takes place, of course, on a subconscious level. Down there in the depths of the human being, the movements of the light-body “strike” – as the ether body is connected with the physical body – everywhere against the physical body and thus transform themselves into memory representations (see GA 165, 2.1.1916). If we could consciously leave the physical body, rid ourselves of it while retaining our perceptions, the memories would stand before us in their supersensible form – as imaginations.

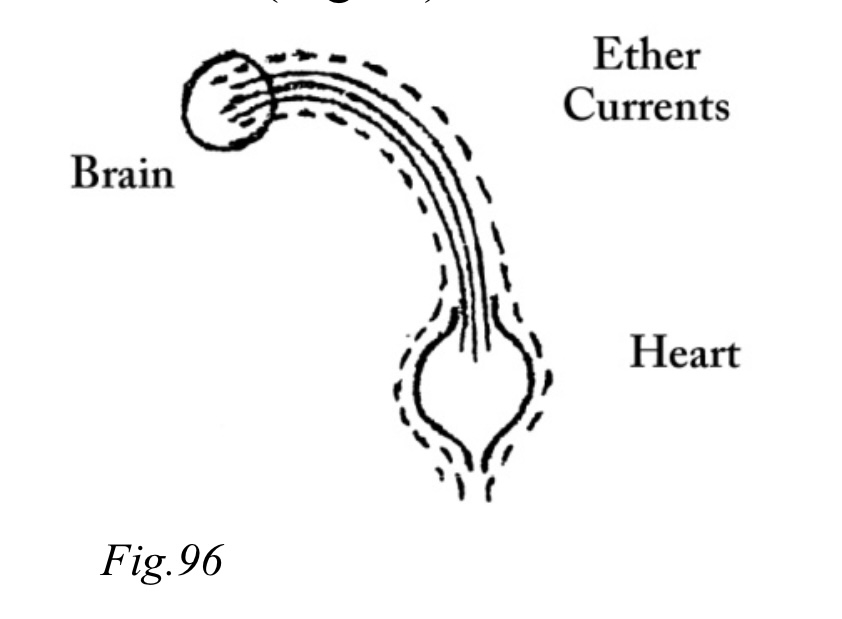

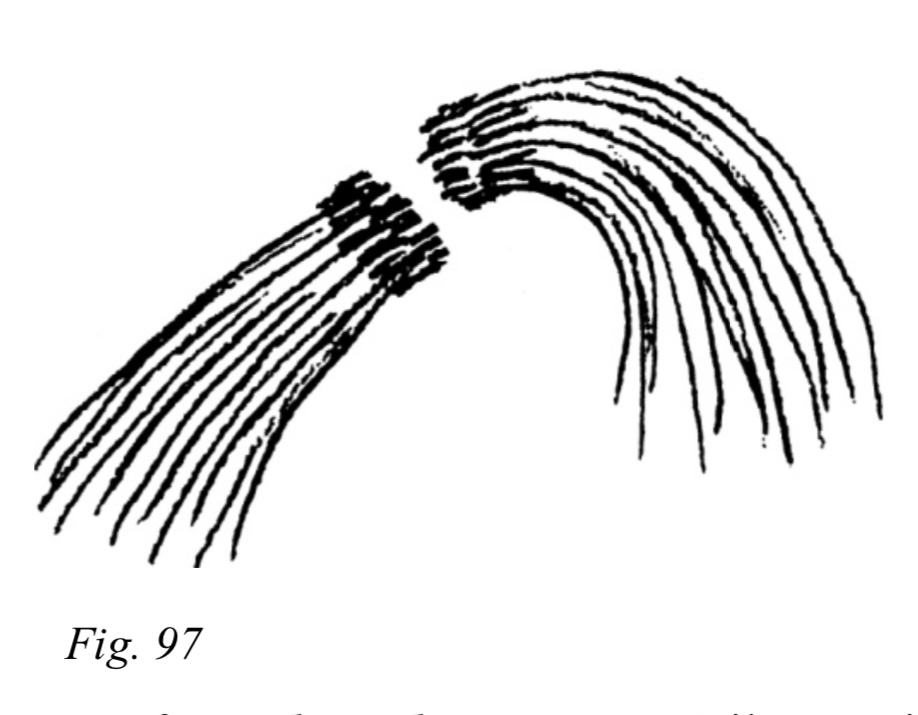

What Rudolf Steiner

calls a “striking” of the ether body on the

physical, he describes in the lectures of the

cycle ‘Occult Physiology’, as follows: Our ‘I’

gathers the impressions of the outer world,

works upon and transforms them in the astral

body and finally imprints them in the ether

body, from where they can be retrieved again as

memory-representations. The blood participates

actively in this process (because it is the

outer, physical expression of the ‘I’). With its

whole movement (especially from below upwards)

it stimulates the ether body; in it various

currents are then formed. They merge with the

bloodstream, flow from the heart to the head and

gather, like unipolar electricity, at a certain

point in the head; there, a great tension of the

ether-forces arises, which become forces of

memory and imprint in the ether-body the

impressions received from sense-perception and

from thinking, with the aim of making them into

memory representations (Fig.96).

Flowing counter to the

above-mentioned current, into a different point

in the head, comes another current – from the

lymph system. When the memory representations

form we have in fact to do with these two

currents in the brain. They stand over against

one another, create a considerable field of

tension, comparable to positive and negative

electricity. A “difference in potential” arises,

which is neutralized when a newly-formed

representation which has streamed into the head

becomes a memory representation – i.e. passes

over into the ether body. The physical organs in

which these two currents are concentrated, are

epiphysis and hypophysis. The first gathers the

etheric current that flows with the blood and

strives to become memory. It radiates out

streams of light that flow across to the

hypophysis, which receives them (cf. GA 128,

23.3.1911). Thus the soul element of the human

being joins together with his bodily nature;

they influence one another. Rudolf Steiner makes

clear what he is saying, with the help of an

illustration (Fig.97).

The process unfolding in this way in the head extends further from the brain along the entire spinal column, it pervades the whole system of the nerve-centres and arrives at the points where the peripheral and central nervous system meet. Here, there is a kind of ‘barrier’, which shuts off the consciousness from the subconscious. Like a mirror, this barrier reflects back the thoughts, keeping them away from the system of the metabolism, and also stops the unconscious element as it approaches in the opposite direction, coming from the other side of the barrier – the element in which is contained the higher ‘I’, which works in the organic processes.

The system of the spinal marrow and brain carries to the blood (the instrument of the ‘I’) the impressions received by the sense-organs. And the sympathetic nervous system, behind which stands the inner (microcosmic) world-system – i.e. the system of the inner organs – has the task of preventing the processes taking place in the organs from being carried into the blood and entering the ‘I’-consciousness. In this way the true, higher ‘I’ of man is closed off from his lower ‘I’.

That which flows from outside into the soul of the human being enters into close connection with the blood and strives to unite with its opposite: with what enters the human being materially. But the latter is confined within the sympathetic nervous system. And the appendage to the brain (the hypophysis) is the sentry that prevents the inner life of the human being from entering his blood. The glands in the human being are the organs of secretion. The stream of etheric forces proceeding from them (via the lymph system) to the hypophysis is accompanied by a secretion that also represents an obstacle to the stream of nourishment when it wishes to enter consciousness via the sympathetic system and be consciously perceived. This is in a certain sense the coarsest form of reflection. External means of nourishment can be compared to spiritual thought-beings – indeed, they are the fruit of their spiritual creative activity and of evolution. It follows from this, that these beings approach us from two sides. We reflect them back and receive concepts above and, below, also a form of consciousness that is extremely dull, but nevertheless essential for the development of ‘I’-consciousness.

The etheric streams that flow with the blood away from the heart are not burdened with the world-encompassing spiritual process taking place in the bodily organs, and they work via the epiphysis upon the brain, thereby making it into an instrument of the soul life. Together with these streams there also flow the currents of the astral body. The brain allows to flow through it the etheric streams but the astral ones it holds fast. These retained currents are, as Rudolf Steiner says, subject to the force of attraction from the external astral substance of the earth. The astral body of man, insofar as enters the head region, is as it were ‘sewn together’ from two astralities: one coming from the Cosmos, and the other arising (from below) from the body. On the head of the human being there is a certain densification which can be compared to a ‘cap’, where the two astralites are ‘sewn together’ by the etheric current. When the astral substance is held fast by the brain it is reflected back, and that is our thoughts, our feelings that have become conscious. But the etheric stream passes through the brain and the astral ‘cap’. And if it is the new etheric of our memory representations, of pure thinking, the etheric of the ‘power of judgement in beholding’, then it forms beyond the limits of the physical brain a new centre of self- consciousness – that which Rudolf Steiner refers to as the “etheric heart”. Thanks to this organ (or centre) “the thought” thinks ... “the thought” (GA 266/2, p.135). In this way the foundation stone of human freedom is laid, as the ‘I’-consciousness overcomes the compulsion of all three sheaths of the human being.

There is yet another peculiar feature of this metamorphosis. The etherized thoughts (memories), in contrast to the astral (those that are reflected), do not transform matter into ash. They dematerialize it. It quite simply disappears from the human being, and the World-Will – the Will of the Father – which dies in the non-organic realm, appears in those places where the vanished matter had been. But as this, however, arises anew as a result of the individual activity of the human being, it is in him the will of his own freedom. Rudolf Steiner says that, at the Baptism in the Jordan, Christ in Jesus united himself with the “newly arising ether body which streams to the brain from the human heart” (GA 129, 26.8.1911). This stream is muddied if the human being bears many desires in his blood, and this dulls the brain. For this reason, the attainment of freedom depends upon moral self-perfection, the ennoblement of the entire three-membered soul.

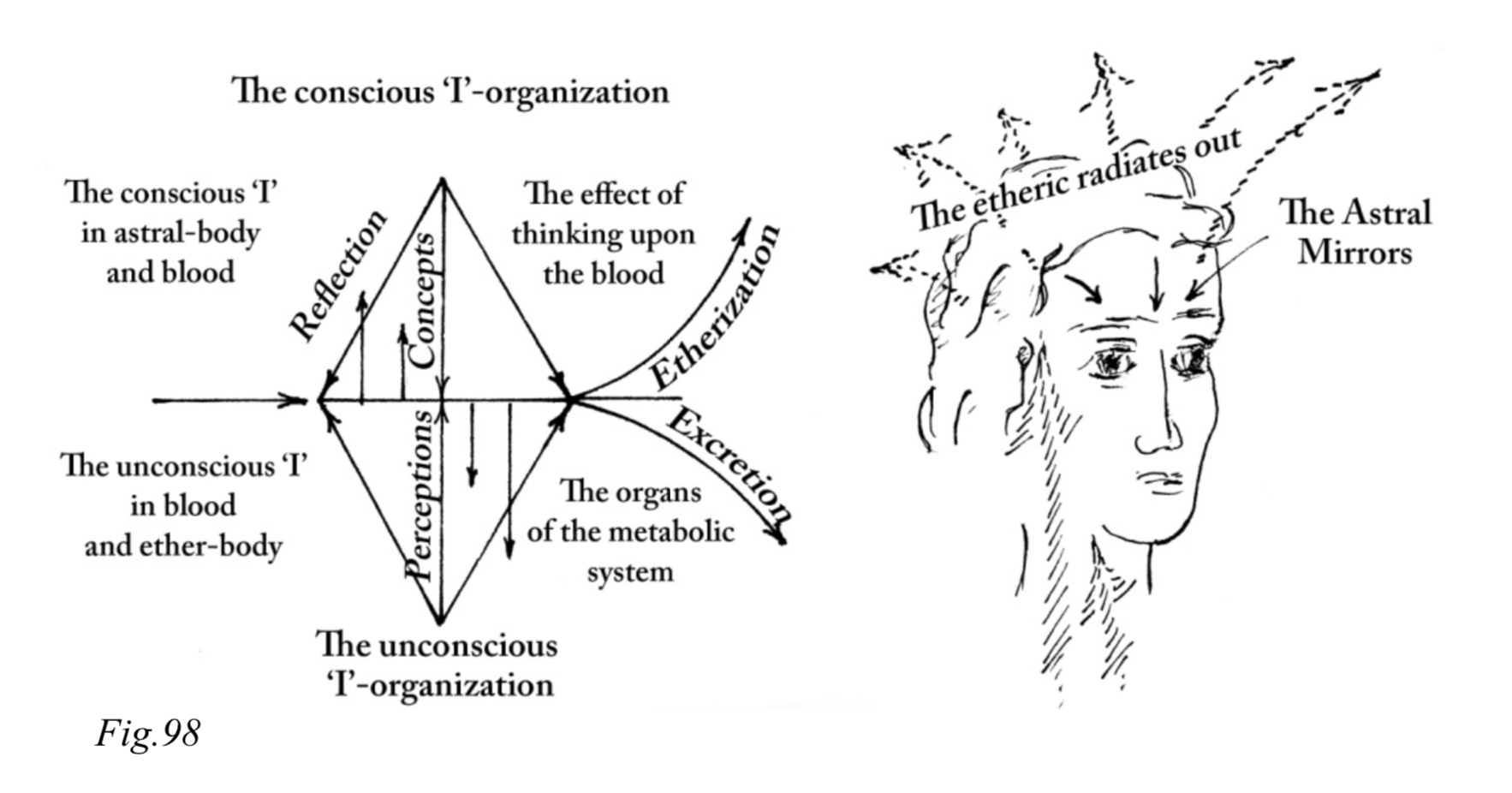

* * *

The two streams we have described spring from the entire being of man, to the extent that he is pervaded by organic activity, but also by perceiving and thinking. Two poles are formed in the human being: the one, through the activity of the self-conscious ‘I’-organization, and the other, through unconscious activity (see Fig.98). The conscious element of the ‘I’-organization has as its basis the sense-impressions, the perceptions, which exert an influence on the blood. Working in connection with it are the brain and the spinal marrow. The impressions stimulate the nerves, these excitations bring the blood into movement; in the points of contact of nerve and blood there arises, as a result of the increased blood-flow, a combustion process which causes a dying of the nerve-cells. As the matter has died, the spirit (thinking), the astral body approaches the ether body and unites with it. But we experience the union of concept and percept. The inner representation is formed, and this is connected with a new kind of etheric nature which arises thanks to the freeing of the ether body from the dead cells. And, what is especially important: this etheric nature is freed as a result of the conscious activity of the human being. This means that we have here to do with a partial awakening to consciousness of our ether body. This is the ether of our memory representations (they arise when the tension between epiphysis and hypophysis is released). But it does not yet become conscious at the point of the uniting of the concept with the percept. It meets up with the counteractive working of the unconscious part of the ether body, arising from the metabolic system, from the water organism represented by the lymph. This is the working of the above-mentioned dull, animalic consciousness of the organism. It is normally referred to as the subconscious.

The subconscious

processes in us are adjoined by our sympathetic

nervous system. This is bound up with the

unconscious will, which also, in fact, drives

the blood to the nerve when a percept begins to

stimulate it (a chemical process in the eye, for

example). This will is rooted in the

blood-warmth (originating from the epoch of

ancient Saturn), and when a splitting of the

nutritive substances takes place (e.g. in the

eye) the warmth that is thus generated does not

destroy the cells of the sympathetic nervous

system; for this reason we do not perceive

consciously what is going on in the metabolic

system. In terms of evolution, its processes

must enter consciousness at a later time, when

the ‘I’-organization is sufficiently developed.

But initially, the lower sphere in man comes

into opposition with the higher when

consciousness arises in the latter. Sensory

perception comes into conflict with the

absorption by the organism, of substances from

the outer world; the subconscious comes into

conflict with waking, object-oriented

consciousness; and this all happens within the

triune human being of body, soul and spirit.

* * *

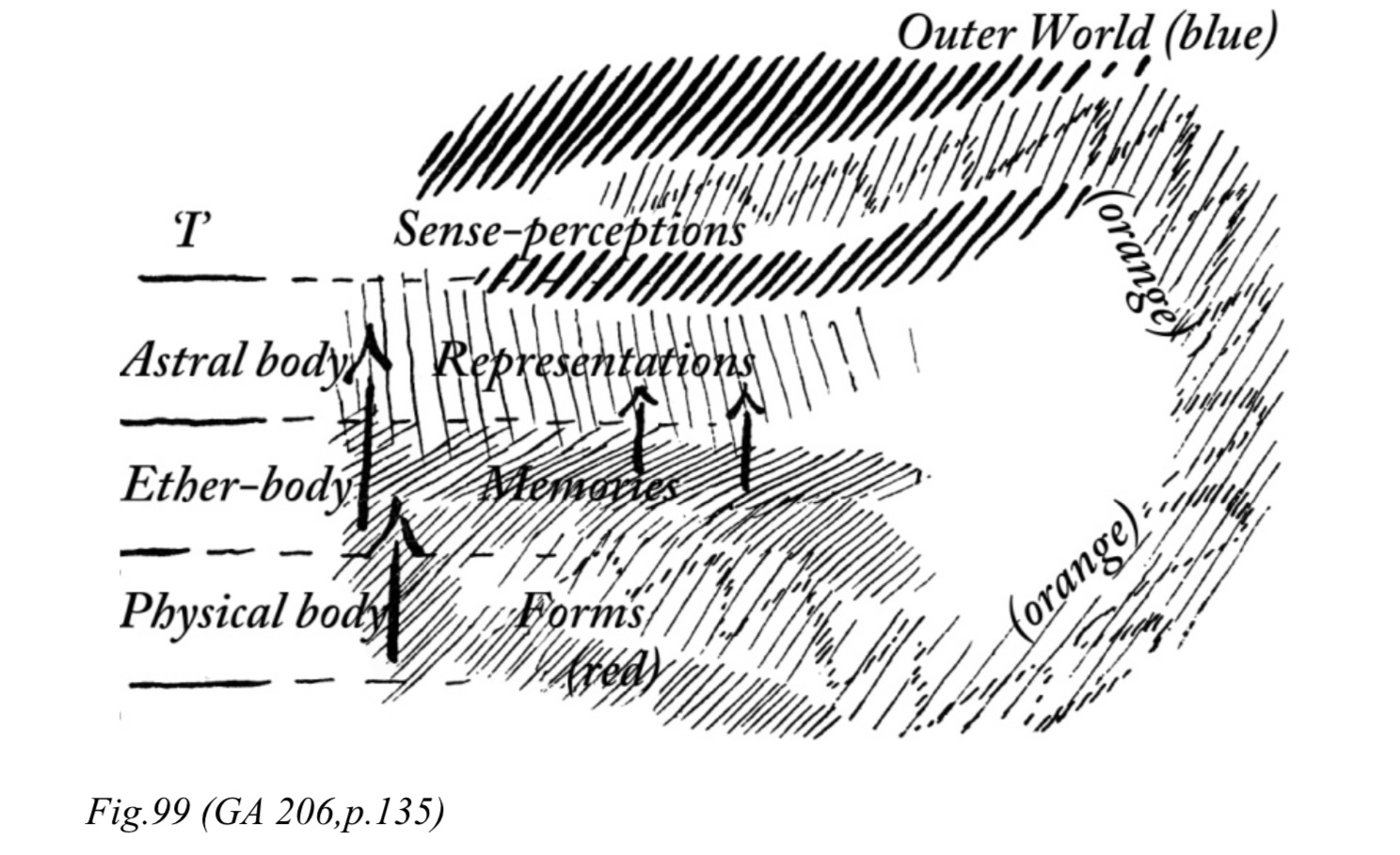

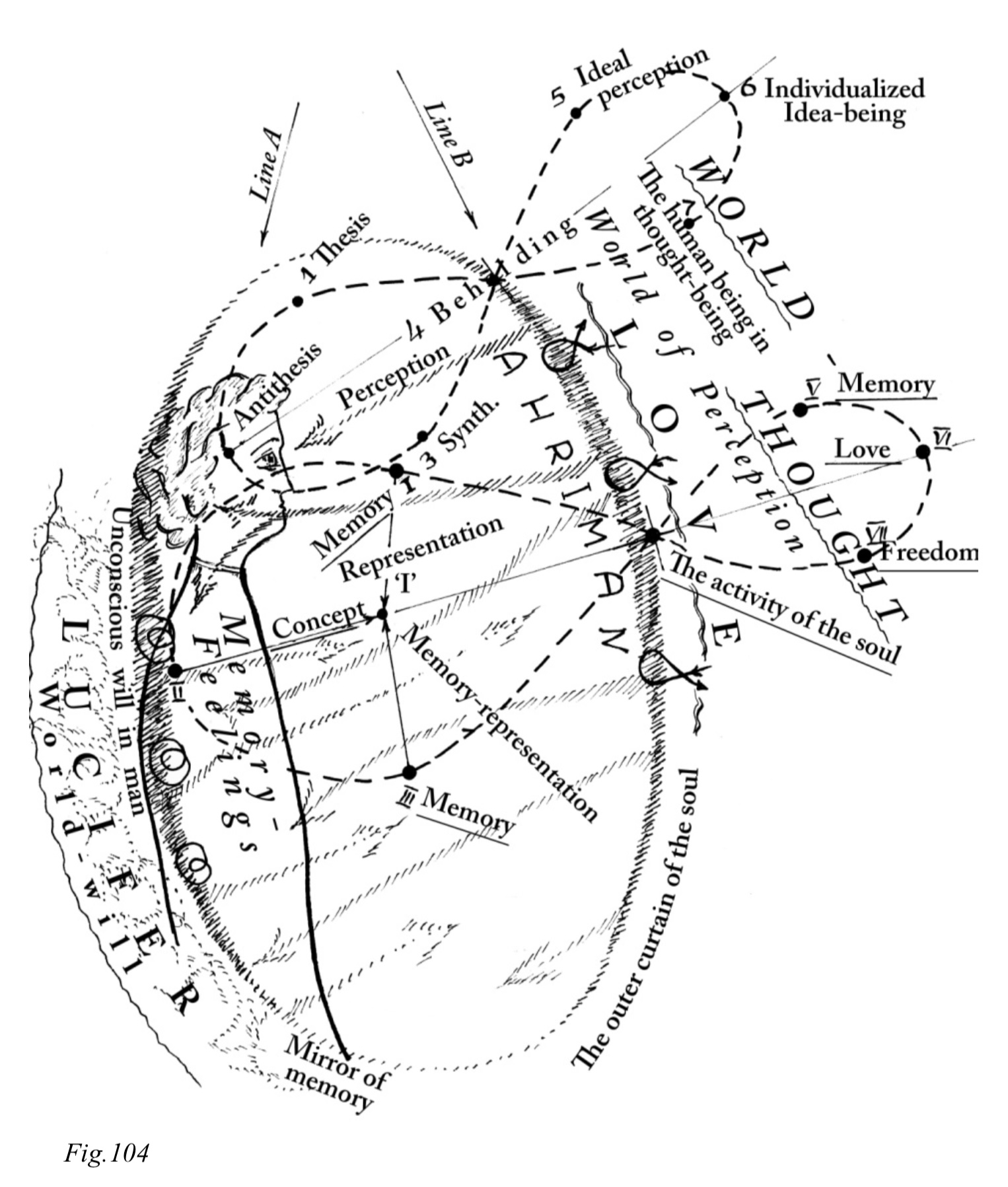

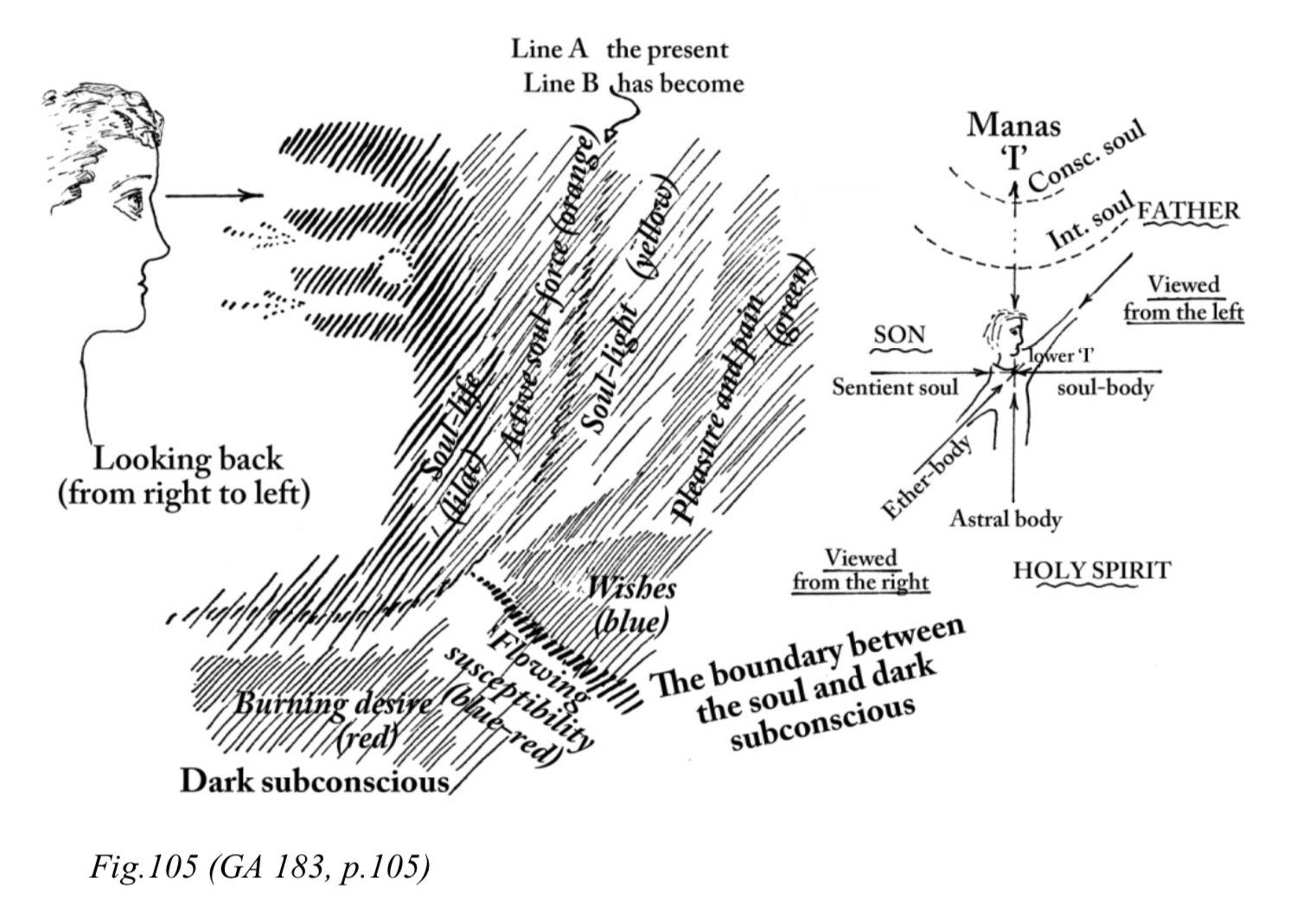

A kind of summary of what takes place in the threefold bodily nature of man and in the ‘I’ in the process of impressing into the memory, is given by Rudolf Steiner in a lecture held in 1921. There he explains his thought with the help of a diagram which we reproduce below (Fig.99). Both the spoken communications and the diagram are of special importance for us, above all because in them the nature of the reciprocal relation of the lower and the higher ‘I’ in the memory process is clarified; we will return to this in connection with Fig. 94. We should not assert, says Steiner, that “our ‘I’... insofar as we become conscious of it, (is) inside us: we experience it from without inwards. – Just as we experience our sense-perceptions from without inwards, so do we experience our ‘I’ itself from without inwards. It is therefore actually an illusion to speak of our ‘I’ as being inside us. If I may express it in this way, we breathe in, as it were, the ‘I’ together with the sense-perceptions, if we think of the taking hold of the sense-perceptions as a finer breathing. So that we must say to ourselves: This ‘I’ actually lives in the world outside (the line in orange, Fig.99 – G.A.B.) and fills us through the sense-perceptions; and fills us then still further as the inner representations (yellow), pressing forward as far as the astral body, connect on to the sense-perceptions (GA 206, 13.8.1921).

With the help of the

perceptions and in the perceptions themselves,

the (higher) ‘I’ stretches out its feelers in

us, so to speak, through to the astral body.

Rising up towards it, come our memories which,

as we said, begin with the shadow-like images in

the physical body. Then they unite with the

activity of the ether-body which, in addition,

awakens the inner representations in the astral

body (arrows in diagram). An etheric-physical

stream arises, flowing from the heart to the

head. In it our ‘I’ is also present. It is also

present in the physical body (red), where it

calls forth the memories (green), which then

become inner representations (yellow).

But already here, Rudolf Steiner continues, the diagram given for clarification becomes inadequate. When we consider the memories, we discover the ‘I’ as something that is in the physical body and does not only come from outside with the perceptions. In order to grasp this phenomenon in its full significance, Rudolf Steiner suggests that we imagine a person standing before us and that we become aware of him/her thanks to the fact that our ‘I’ is present in him/her and reaches us in the perceptions. If we have seen this person before, our inner ‘I’ encounters in memory the first ‘I’, which comes with the perceptions. They meet, and we recognize the person.

The ancients expressed this phenomenon in the form of a serpent that bites its own tail; in modern times it is more appropriate to use the picture of a human being standing before a mirror. Let us imagine that he has no knowledge of his own existence, and that the experience of his reflection in the mirror represents his first knowledge of it. Then pointing to the mirror-image, he says: That is me. We are doing something exactly like this when we describe our everyday ‘I’ as the genuine one. No – our true ‘I’ strives towards us from outside in the form of a kind of stream and enters us through the stimulus of the sense-perceptions. When it reaches the physical body, it pushes this away. This act of repelling is perceived by us in sentient experience.

Thus our concepts, our inner representations, are also reflections of the experiences that come into us from the outer world – the outer world, in the sense that they arise within the sphere of our true ‘I’. And in this case, when we return to the antitheses ‘I’ and world, ‘I’ and not- ‘I’, we must say that the world is the ‘I’. So, what is the entity that we regard as the ‘I’? It has a twofold nature. Our waking consciousness is the form of the real existence of our higher ‘I’ which, unconscious for us, enters us via the astral and ether bodies and reaches through to the physical body, by which it is reflected back. Thanks to this process of reflection, we become conscious of our sense-perceptions and inner representations. They are all images of the true reality, but lack substance, and we can therefore join them together in whatever combination we wish. And therein lies the activity of the lower ‘I’. In it we are free: through it is posited the beginning of the higher freedom.

Such is the nature of our (human) subject. It is shadow-like, but its basis is constituted, though unconsciously to begin with, by our higher ‘I’ which comes to us as object. From a certain moment – or a certain stage – onwards, subject and object begin to coincide: when our inner representations become memories. The higher ‘I’, which remains in the subconscious, works in the process of remembering; here we have to do with the reality in us. What its nature is, in the being of the three bodies, we have already described.

* * *

When the human being perceives and thinks, he experiences within himself a process with two stages. On the subconscious level the senses, so Rudolf Steiner says, accomplish “a process that I do not perceive; they vitalize for me the real process into my inner being (this is how the higher ‘I’ works in them – G.A.B.) for mental representation. So that, when I have a sensory perception, I initially form by way of this sensory perception the inner representation; but then a second process is there, through which something real is brought about, not merely a picture.... When I remember, then this inner representation sends its influence upwards, just as the sense-perception did previously, and I perceive what was really conjured forth in me when I had the sensory representation, but without realizing it” (GA 212, 30.4.1922).

It is in all circumstances necessary to bear in mind what has just been said, when we are working with the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. The inner representations of which its content is woven are encountered by the reader again and again in the most varied elements of their structures. Particularly often the theme of naïve and metaphysical realism is discussed. And we must realize that we have to do here, not with empty repetition, but with work in the different parts of the soul.

Thus, we are developing “results of soul-observation”, and not results of a speculative or any other kind. To encounter for the first time the attitude of naïve realism is one thing; it is quite another thing to draw it up from the memory in the form of different inner representations which serve, in the one case, a given synthesis and, in the other, ‘beholding’ etc. In this way is woven the fabric of ontological, ‘beholding’ thinking – frequently parallel to the conceptual. If one does not know what it is all about, one can very well fail to notice the development of the thought as ‘beholding’. Then it also remains “esoteric”.

This is the new and remarkable way in which the soul-life of the ‘I’ can unfold – the personal life of the human being. In this life we are woven out of our memory representations. And the task stands before us: How can we unite with the reality of the memories, ascending to it from the memory pictures, which are without substance? Rudolf Steiner recommends that we carry out an inner “reversal” – turning our soul towards the place from which our memories rise, which bear within them our true ‘I’. This requires the development of great mobility of soul, whereby we come into contact in our consciousness with the element of the will, as subconscious processes are inadequate here. For this reason the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ places a main emphasis on the question of the carrying of the will into the thinking, for this is where the higher soul-life begins.

* * *

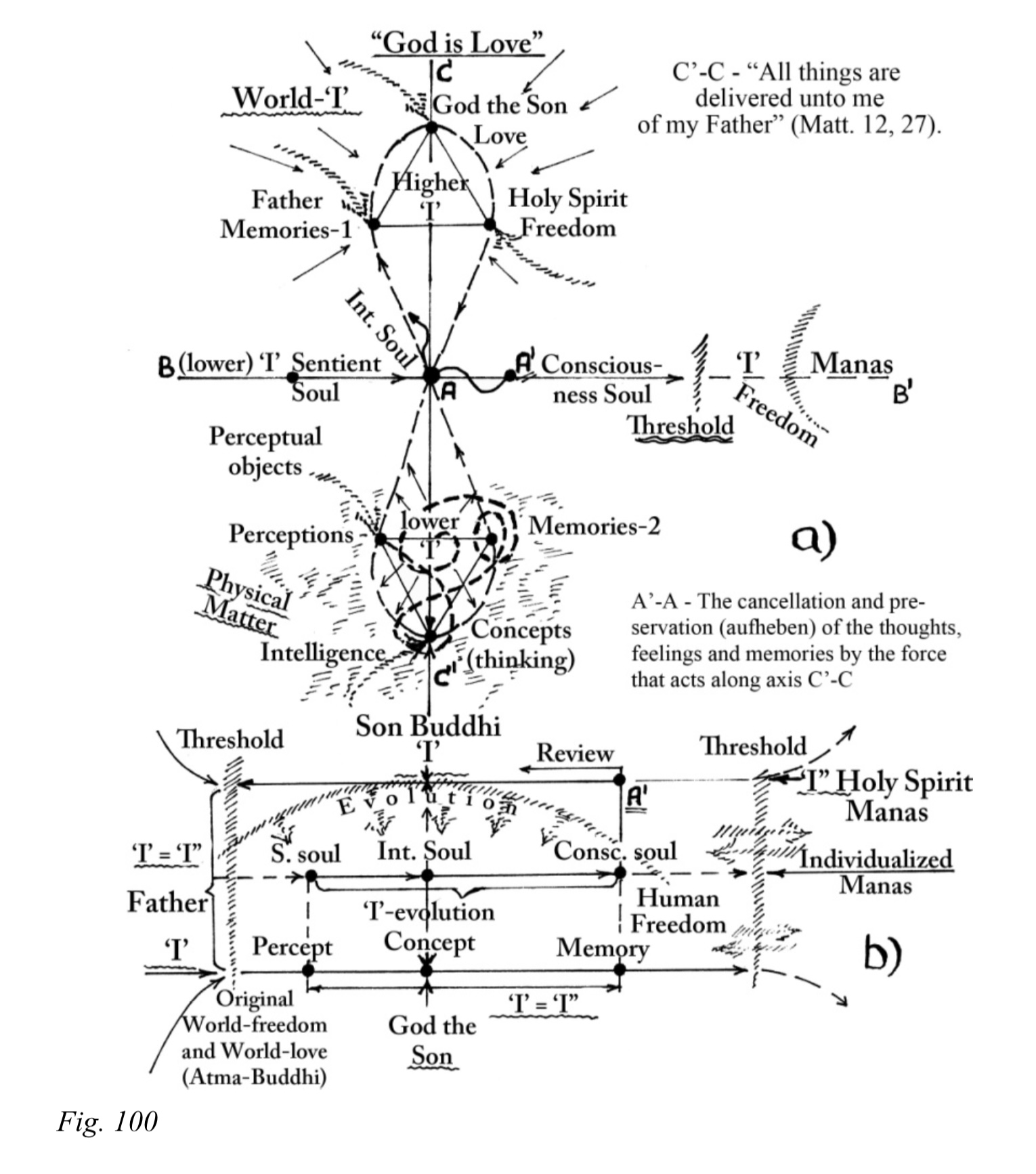

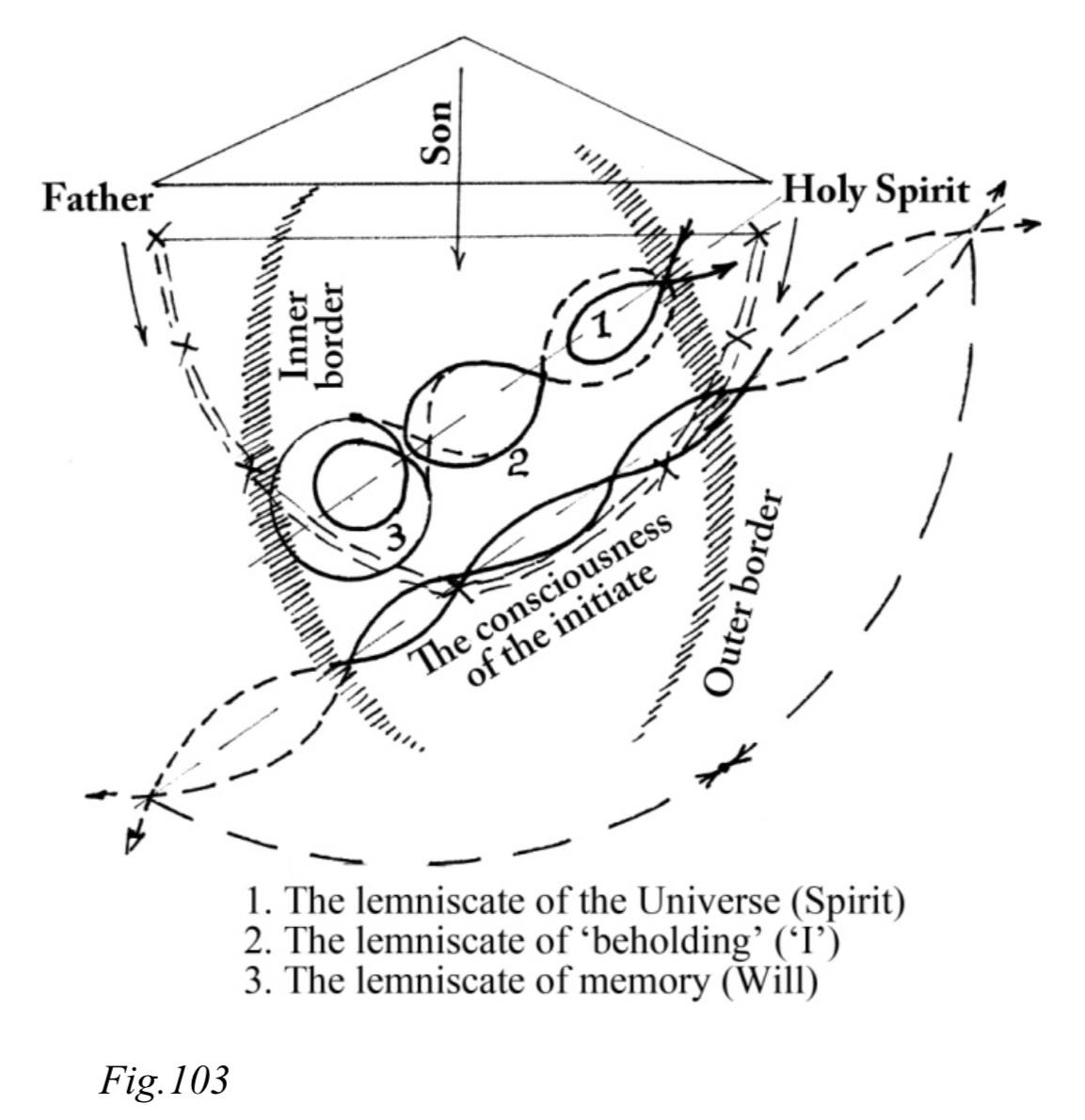

These discussions make possible for us a broader and more detailed development of the theme, whose picture we have represented as a synthesis in Fig.94, by means of a lemniscate. Here we have before us a symbol of the ‘ur’-phenomenon of man, which is realizing itself at the point of the transition of the subject from sensible to supersensible reality. In this state the ‘ur’-phenomenon represents a system that is, both in its lower and its upper parts, open and at the same time autonomous, and therefore – from the standpoint of the universalism of the evolution of the microcosmic ‘I’-consciousness – also self-contained (see Fig 100a). In the upper part of the lemniscate the system of the primordial revelation of the triune God is open, through which was posited the ‘becoming’ that is, on all its levels, seven-membered.

In the system of the

microcosm the primal tri-unity manifests the

peculiar feature, that the hypostasis of the

Holy Spirit forms within the element of the

higher memory an entirely inward phenomenon,

whose reality grows to the extent that the human

being possesses an individual Manas. This is the

sphere where the human being has the task of

attaining to free imaginations. The lower ‘I’,

which lives from the content of the lower memory

representations, is separated from the higher by

the sphere of the subconscious, which it strives

to imbue with the light of cognition, on the

path of the development of the triune soul. We

have shown this part of the diagram again,

separately, so that it can be studied more

closely.

In the course of evolution, and of the cultural-historical process in particular, the human being undergoes his development from the sentient to the consciousness-soul, using the support provided by the experience of perceptions, feelings, thinking and action. To begin with, on the stages of group-consciousness, there stands behind these the higher ‘I’, which was bestowed on humanity by the spirits of Form and has ‘Father God’ character. Within it work the primordial world-freedom and world-love which in otherness-of-being, before they become freedom and love in the individual human being, are turned into predestination and duty. Let us call this working (the totality of Atma and Buddhi) – Iʹ. The everyday ‘I’ of man, which lives in the threefold soul, approaches the individual higher ‘I’. Let us call it – Iʺ. It ascends continually the stages of likeness to God and is able, potentially, to identify with the world-‘I’. The sphere of individual human freedom extends – as will be shown in our analysis of chapter 9 of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ – between the consciousness-soul and Manas. Study of the evolutionary constellation of the Trinity in the upper loop of the lemniscate (Fig.100a) will explain to us why, above the sphere of the consciousness-soul, one can experience conceptual and moral intuitions, and not imaginations. The relation Father – Holy Spirit has revealed itself to evolution from its beginning. Therefore this very relation, above all, is also revealed to the individual soul at the height of its development: conceptually in the aspect of Manas and intuitively in the aspect of Atma. But in this way the human being receives only the idea of freedom. If he is to be able to bring this to practical realization, the Second hypostasis must reveal itself – in moral intuition.

As a preparation for this state, in which freedom is born, the Manas in the three-membered soul unites with the lower ‘I’, which calls forth in it an involutive process; this comes to expression in the development of the memory. The (lower) ‘I’ itself works within the soul as the power of remembering. In the consciousness-soul this power can grow to the point where the (lower) ‘I’ receives the capacity to look back in time (point A’, Fig.100b), but it sees, not itself, but the world-‘I’ that works in evolution; admittedly, the precondition for this is that the (lower) ‘I’ is cancelled and set aside and that consciousness is maintained in pure actuality.

Steps of this kind are taken by the human being in the flow of time, along axis BB’, which is also the threshold of the supersensible world. Vertical to this axis of symmetry, there runs the working of the impulse proceeding from God the Son. He it is who, after the Mystery of Golgotha, leads us in the condition of the cancelled and preserved (aufgehoben) ‘I’ over the threshold of the point of nothingness of the lemniscate. The success of this action can be judged by the degree to which the intuitions received on the other side prove, when connected with the practical life, to be moral and free from the egoism of this side.

One can say that in the lemniscate in Fig.94 we have before us the “what” of the microcosm, whereas in Fig.100 its “how” is revealed to us and, therewith, the method required to solve the problem we encounter at the nodal point of the lemniscate. As we acquire in the consciousness-soul the strength to look backwards to the higher (evolutive) Iʹ which works in our memory (in it is hidden the entire foregoing evolution of the world), we approach in the “retroactive” movement of the cancelling and preserving of the ‘I’ (which is identical with the intellectual soul) the nodal point (A) of the lemniscate, and there we are taken hold of by the forces of the metamorphosis of lower processes to higher and are borne upwards. It is clear that in this situation the decisive role is played, not by the feelings and thoughts, but by the element of the will. And in the case in question this is the will of God the Son, who says: “My meat (i.e. real life – G.A.B.) is to do the will of him that sent me, and to finish his work” (John 4, 34). In Christ is united the world-will of the Father with concrete love for the human being, love of the human being to his fellow-men, love of the human being to the object of cognition. The blind love arising from the blood relationship is imbued with the light of knowledge, with the Holy Spirit.

Of Christ it is said: “God is love.” In his working within the human being, Christ helps the one who walks, to overcome the egocentricity of the abstract ‘I’, to develop love for the world as for himself and thus for his own higher ‘I’. In such a case one can, without hesitation, “die” on the cross of the world-principles (BB’ – CC’); that is, extinguish percepts, thinking, the earthly memory: “For whosoever will save his life shall lose it (in increasing materialization and abstraction – G.A.B.): and whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it” (Matthew 16,25). Not everyone is ready and able to take upon himself so concretely and practically “his” cross, which is at the same time the world-cross. But whoever fails to take it upon himself, will not resurrect.

4. The Phenomenon of the Human Being

The human being as a phenomenon embodies a sensible-supersensible totality of processes which are permeated by a unitary organization. From a certain point of evolution onwards the nodal point of this organization shifts from the spirit (the group-‘I’) to the physical body, which explains the decisive significance of the earthly incarnation for the evolution of the human monad to an ‘I’-being.

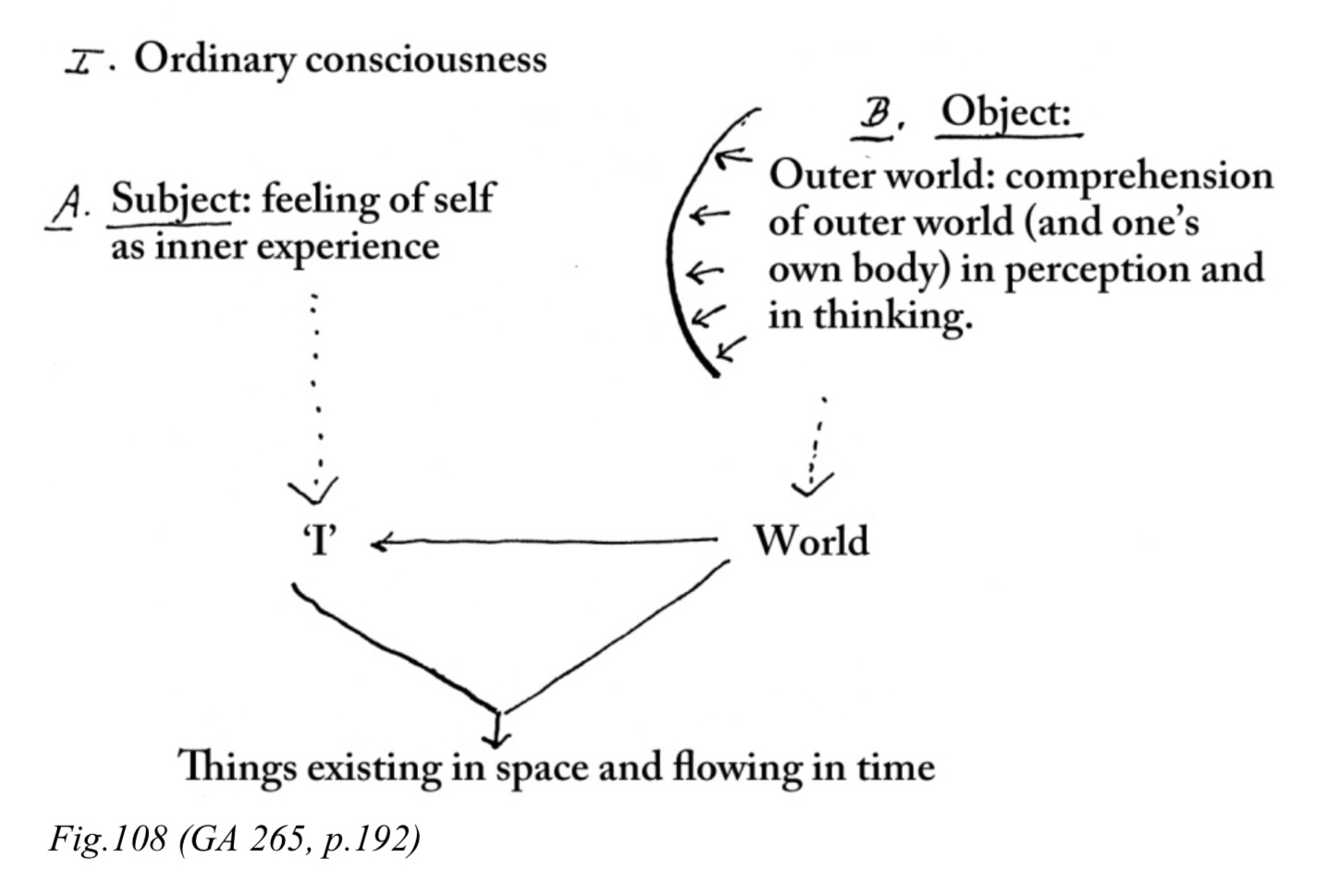

This organization is a system whose elements and connections do not all become conscious to the human being. Their being made conscious is the movement from lower to higher ‘I’, which is a process of self-realization. Its various stages consist in the establishing of boundaries, the “membering-out” of the phenomenon of man from the complex phenomenology of the macrocosm. In this sense we are – as Rudolf Steiner emphasizes – quite simply schematizing when we speak of man as a many-membered being consisting of, for example, physical body, ether body, astral body and ‘I’, because in no circumstances do these members delimit, separate him off from the material-spiritual world around him. They are merely elements of the organization which are endowed with a content by the processes taking place within them. The boundaries of the human subject are formed thanks to the fact that in it the following arise: 1. images, 2. experiences of inner representations, 3. experiences of the memory, 4. experiences of perceptions (cf. GA 206, 12.8.1921).

An examination of these boundaries provides us also with an answer to the question of the limits of knowledge.

Let us return briefly to the way this process of boundary-forming stood before us in the previous discussion. Perception which has be- come an experience within us brings the universal activity of the ‘I’ into connection with our earthly individuality. The percept becomes the possession of our emerging everyday ‘I’. In addition, our inner representations (cf. Fig.99), which have been ‘implanted’ in the ether-body, become percepts. In the first years of childhood there arises already a certain ‘blockage’. The perceived inner representation is reflected back by the physical body and there emerges the capacity to remember. If no blockage were to arise in the physical body, so Rudolf Steiner says, the human being would be at the mercy of outer events and imitate them in an empty fashion. For this reason, what we experience in the outer world must not pass through us; we must hold it back, and this is what our physical body does.

The individualization of the soul-life begins, therefore, with a process in the physical body that is conditioned by the body’s materialization. This has made the body impermeable to sense-impressions which, for their part, have assumed an earthly character. The physical body itself consists of a working together of forces and pictures. But underlying both is the working of the ether-body upon which the physical body imposes its laws.

Then, also the astral body and ‘I’ work upon the ether body. There arises a complex system of forces and their effects which permeate the entire fourfold man. “If,” says Rudolf Steiner, “you imagine the forces of growth from the inside, and think of them as permeated on the other side by that which underlies memory – but now, not as inner representations that hide one another, but as that which lies at the basis of memory – in other words, etheric movements on the one side, which well up and are dammed up through the inner processing of the nutritive substances taken in, and are dammed up through the movement of the human being, in conflict with what wells downwards from all that has been perceived through the senses and has become inner representation and has then descended into the ether-body in order to preserve memory; if you imagine this interworking from above and below, of what swings down from the inner representation and of what rises up from below from the process of nutrition, growth and eating, both of these in interplay with one another; then you will have a living picture of the ether body. And again, if you think of all that you yourself experience when instincts (in the subconscious – G.A.B.) are active, where-by you can understand very well how in the instincts there work blood circulation, breathing, how the whole rhythmic system works in the instincts, and how these instincts are dependent on our upbringing/education, on what we have absorbed (also in the memory – G.A.B.), then you have the living interplay of what is astral body. And if, finally, you imagine an interplay of the acts of will – in this realm everything is stirred up that has the character of will-impulses – with what are sense-perceptions, then you have a living picture of what, as ‘I’, lives its way into consciousness” (GA 206, 12.8.1921).

In concrete terms, fourfold man is also constituted in this way. We need this description in order to grasp the “atomistics” of soul life, not in its sensory allegory, but in its sensible-supersensible essential nature.

Let us suppose we have received a sense-perception of the colour red. If we reflect upon it, then we have distanced ourselves from it in our ‘I’. But while we are perceiving it we ourselves are merging together with it with our higher ‘I’ and our entire astral organism. The colour fills our consciousness completely. The perceiving of it also calls forth significant processes in the physical body. It is well-known that the human being consists, to more than 90%, of fluid. The organs that regulate the watery organism are the kidneys.* They have a relation to all the watery processes, also in the eye. The watery element, says Rudolf Steiner, is in a certain sense "rayed out" from the system of the kidneys over the entire organism. And this is living water. On its waves move the outward radiations of the ether body. It is in this way that they reach the optic nerve. Moreover, the picture that in the perceptual process has arisen in ‘I’ and astral body streams into the fluid that fills the eye and is permeated by the ether body. Thus the act of visual perception is conditioned by the connection of what comes from without and what comes from within.

* These are also closely

bound up with the airy organism.

______

Within this phenomenon

of soul-life the triune human being of limbs,

rhythm and head comes to expression in a special

way. Rudolf Steiner says that throughout a human

life the head (from which plasticizing,

form-building forces stream into the organism)

is continually attacked by the metabolic-limb

system. Their relation is mediated by the

rhythmic system, and this process has an effect

upon the functioning of all the organs. Let us

again take the eye as an example. This is

pervaded by the blood vessels and therefore also

the metabolism. Here, "that which takes place in

the venous membrane of the eye (in perception –

G.A.B.) ... (wishes to) dissolve, already in the

eye, what wants to consolidate itself in the

optic nerve. The optic nerve would like

continually to create (on the basis of the

perception – G.A.B.) clearly-contoured

formations in the eye. The venous membrane, with

the blood flowing there, wants continually to

dissolve it”* (GA 218, 20.10.1922).

Both activities have the character of a

vibration. The relation of their rhythms is 1:4.

These processes are of an extremely fine nature.

Rudolf Steiner advises that, if we wish to

understand them, we should abandon the crude

assumption according to which the arterial blood

passes over directly into the venous. In

reality, the blood pours, in the rhythm of its

circulation, from the artery (into the organ)

and is then sucked up by the vein, pours again

and is sucked up again. Here, the rhythm of the

circulation prevails. In the optic nerve,

however, vibrates the rhythm of the breath. The

process of seeing consists in the fact that the

two rhythms strike up against one another. Their

ratio is 1:4. This is the relation of breath and

circulatory or pulse rhythm. If the rhythms were

the same, visual perception could not occur. And

behind them stand the astral and ether bodies;

their mutual influence determines the state of

the entire organism. If the former changes, the

relation between the processes of hardening and

dissolving is disturbed, with illness arising as

a consequence.

* Incidentally, here the

same world principles are at work as those that

stand at the beginning of the universe:

substance, life, form/

______

When the perception has taken place in us, it becomes conscious. Then the rhythmic process, “which is regulated by the heart and the lung,” propagates itself “via the cerebro-spinal fluid up into the brain. ... Those vibrations in the brain, which occur there and have their stimulus in the human rhythmic system, are that which, in fact, conveys physically the understanding (of what was perceived – G.A.B.). We can understand by virtue of the fact that we breathe. ... However, through the fact that the rhythmic system is connected with the process of understanding, the latter comes into a close relation with human feeling. And anyone who cultivates self-perception of an intimate kind can see what connections exist between understanding and actual feeling” (GA 302a, 21.9.1920). What then happens, is that everything sinks down into the system of the metabolism, the internal organs, where it becomes memory.

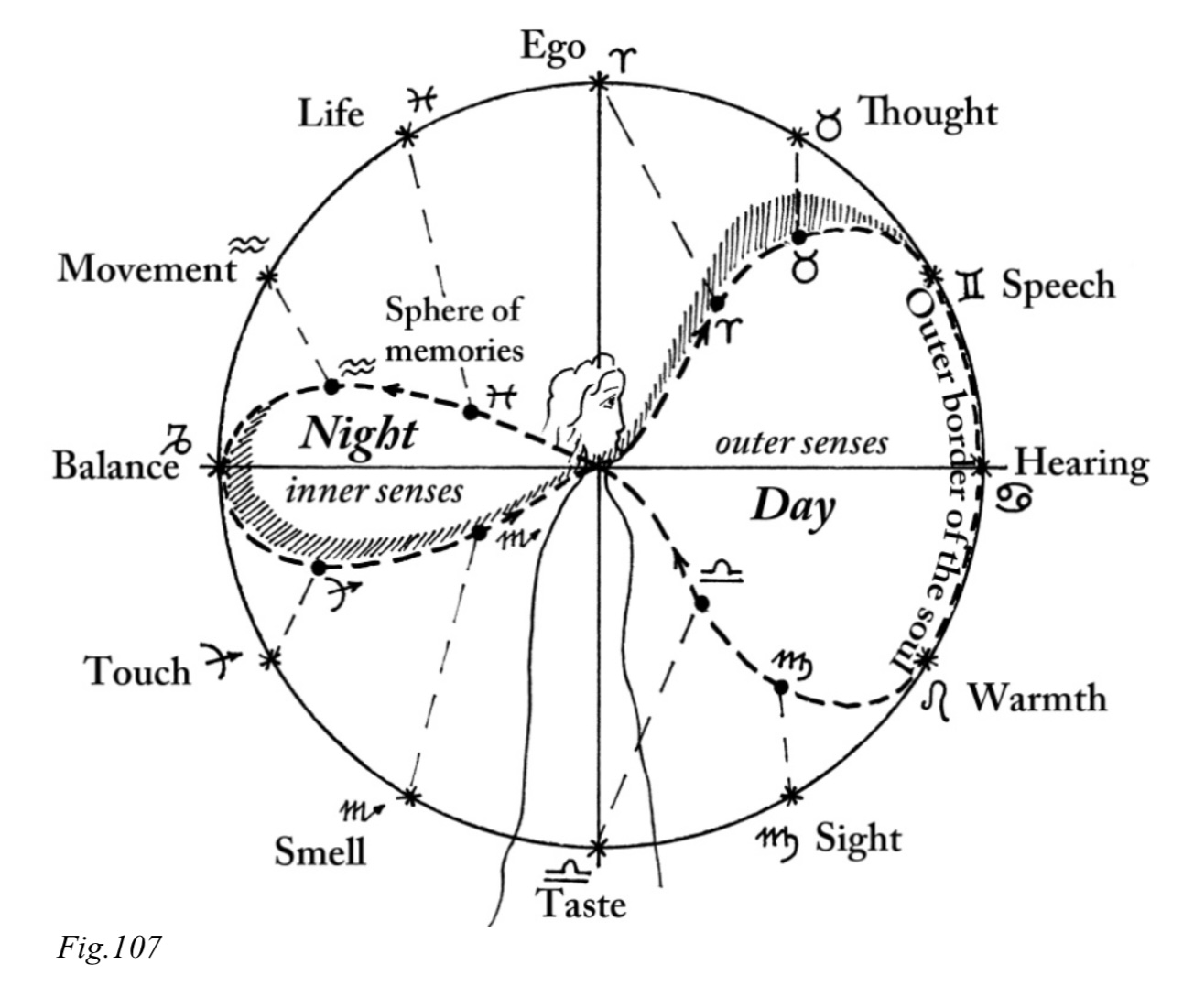

Not all sense-perceptions function in the way described above. In the human being there are altogether, as Anthroposophy teaches, twelve forms of sense-perception, and they are capable of development. They can be divided into three groups, such that in the first group the nature of thinking and of the forces that build it up comes to particularly clear expression; in the second, the nature of feeling; in the third, that of the will. The sense of hearing belongs to the last group. It is in a certain sense the antipode to the sense of vision. Their opposite nature lies in the fact that vision is mediated by the sensitive nerves and hearing by the motor nerves. Here we must bear in mind that in reality all human nerves are sensitive. The motor nerves allow the human being to perceive with the sense of movement (the second in the system of the twelve senses). And, as Rudolf Steiner says, they have “nothing to do with the stimulation of the will as such” (ibid.).

What we hear penetrates via the auditory nerve deep into our organism and, in the nerves, takes hold of that which normally only the will works upon if it is to be perceived by us. It is therefore no coincidence, Rudolf Steiner remarks, that Schopenhauer experienced music as being closely bound up with the will. What we hear is perceived by the whole system within which the will is rooted in us: namely, the metabolic-limb system, where all that has happened is imprinted in our memory. What we have heard is recalled to memory in the place where what we see is perceived – in that part of the metabolic system which reaches up into the head.

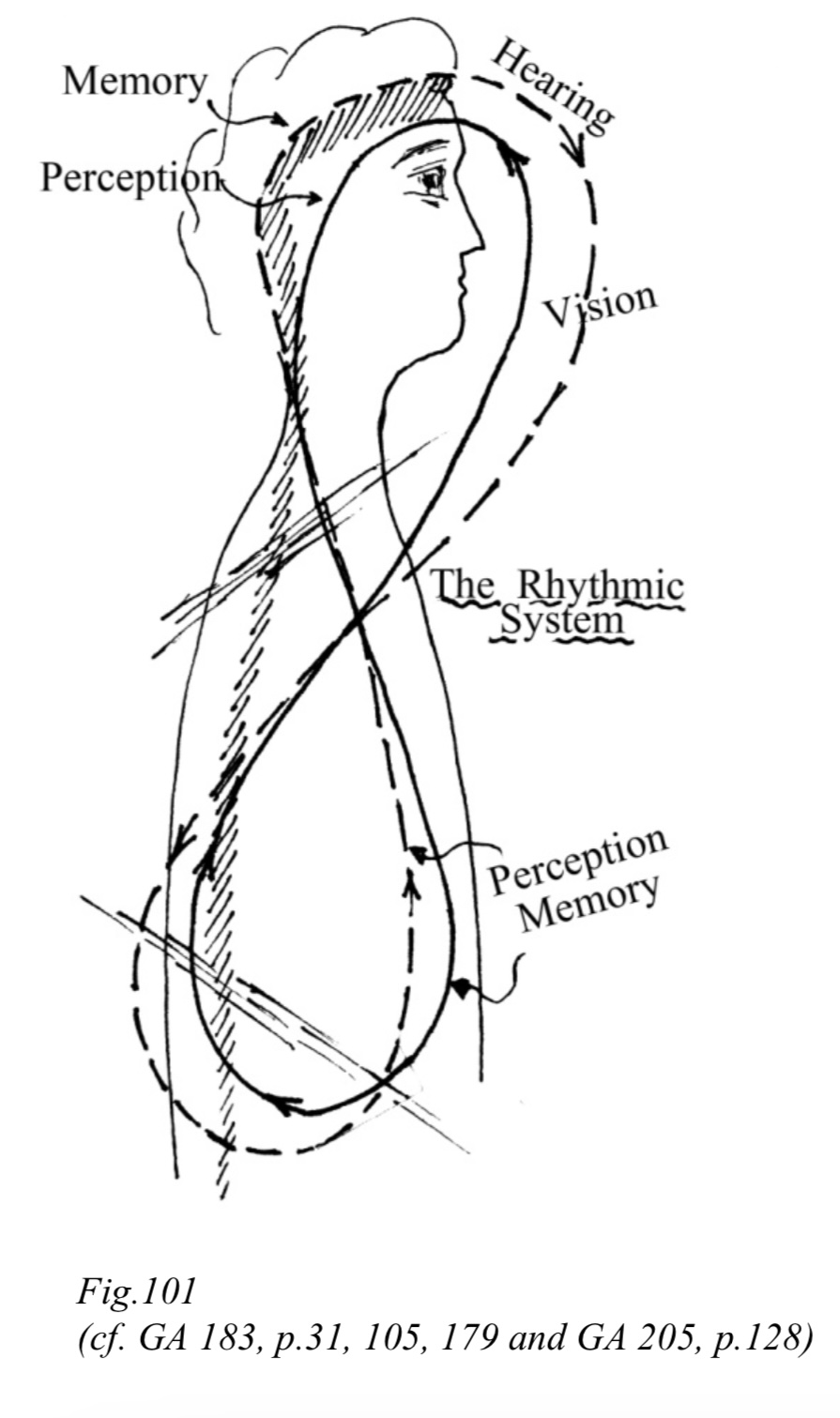

The inner representations arising from the senses of sight and hearing are understood with the help of the rhythmic system. Thanks to this, they come into a reciprocal relation; they cross each other “like a lemniscate in the rhythmic system, where they reach into and across one another”. In this process, “the visual representations” have “a stream into the organism; the aural representations have a stream from the organism upwards” (ibid.). The development of the speech organs is connected with this orientation of the stream of aural experiences.

* * *

On the basis of the

single examples we have discussed, we can

present the main features of

bodily-soul-spiritual ontogenesis which has,

already on the level of sense-perceptions, the

character of a system (Fig.101). The polar

inversion of their twelve-membered totality

(from the sense of life to the sense of ego) is

related, and is analogous in its functioning, to

the polar inversion of the nerve-sense and the

metabolic-limb systems. The two types of

inversion share a common element – namely, the

rhythmic system of breath and blood circulation.

Behind the activity of all three systems stands

the higher ‘I’ of the human being. The systems

mediate its connection with the body, and

sense-perception mediates its connection with

thinking, feeling and the expression of will. If

one removes one of the elements from this

totality, its holistic, spiritual-organic

character is destroyed, thus making access

impossible to knowledge of the qualitative side

of the phenomenon of man.

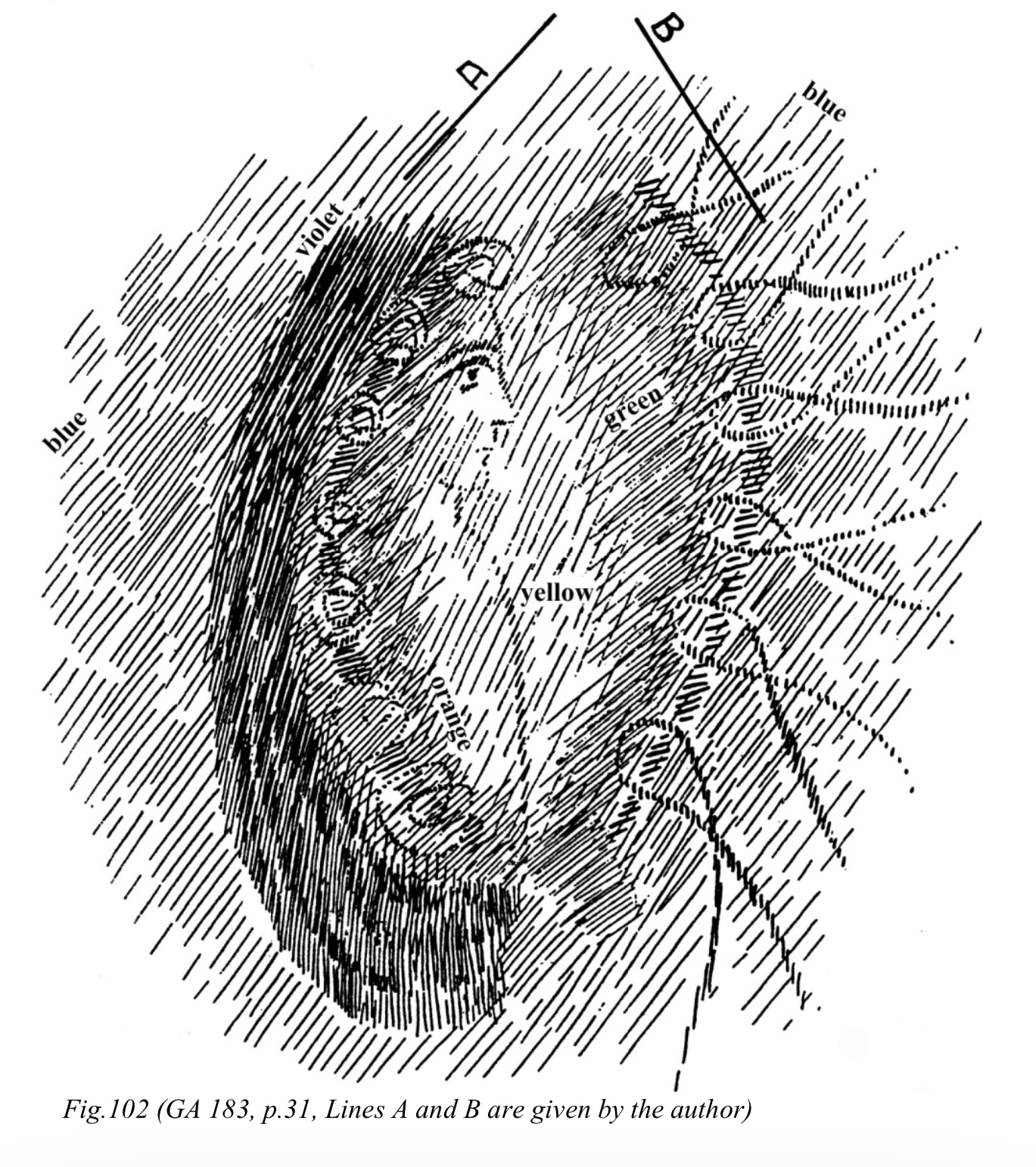

In one of his lectures

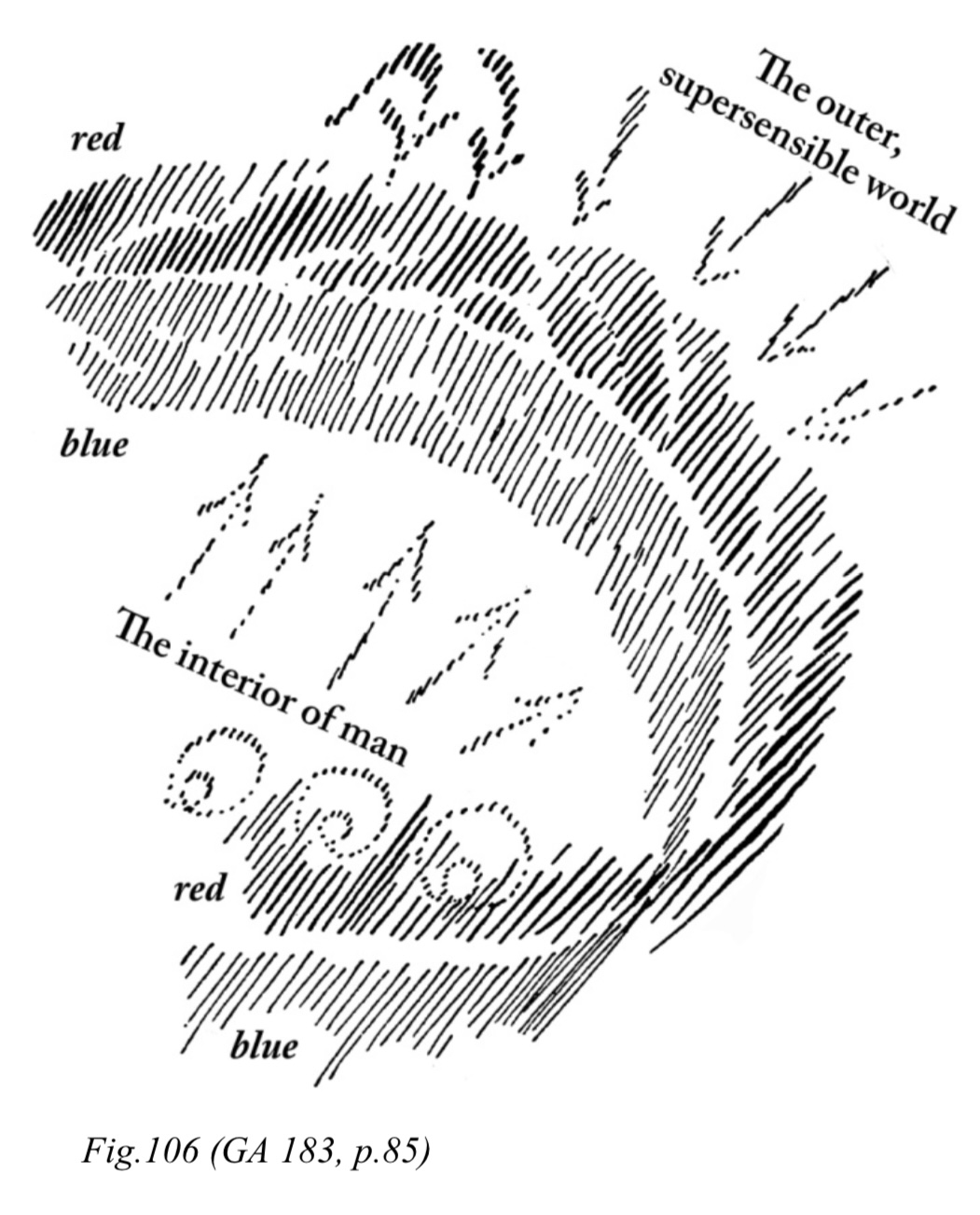

Rudolf Steiner presents an illustration of the

human aura viewed in profile from the right.

This is reproduced here in Fig.102. We have made

to what has really been beheld, a small

diagrammatic addition in order to crystallize

out the lasting elements within the continually

changing process which the aura is, or rather to