Rudolf Steiners "Philosophy of Freedom" as the Foundation of Logic of Beholding Thinking, Religion of the Thinking Will, Organon of the New Cultural Epoch

Volume 2

Part VII. From Abstract to Picture Thinking

1. Primary and Secondary Qualities

2. Some Special Features of Quality and Quantity

3. What is the Relation between Thinking and Being?

4. The Divine and the Abstract

5. The Pure Actuality of Thinking

Chapter 5 – Gaining Knowledge of the World

1. Primary and Secondary Qualities

Among the various philosophical, Goetheanistic and spiritual- scientific definitions of the human being given by Rudolf Steiner, we do not find a more universal and in a certain sense more radical answer to the question: Why did man become a thinking being? – than in one of the lectures of the cycle ‘The Deeper Secrets of the Human Being in the Light of the Gospels’. There, he says: “Why did the Gods create human beings? The reason was, that only in the human being could they develop capacities... of thinking, of representing things in thought in such a way that his thoughts are bound up with the making of distinctions. This capacity can only be developed on our Earth; prior to this it had not existed at all, it had to wait until human beings came into existence.... The Gods brought man into being in order to receive back from the human being what they had, but now in the form of thought.... And whoever does not want to think on the Earth deprives the Gods of what they had counted upon, and is therefore quite unable to achieve what is actually the task and mission of the human being on the Earth” (GA 117, 13.11.1909). The words of Rudolf Steiner quoted here can be compared to a tight, inward-spiralling movement, whose unwinding, which extends in both directions – back to the original, Goetheanistic-philosophical period of his activity, and forwards to its final stage, where he developed the ideas of reincarnation and of the Michael impulse – represents the “keynote” of his entire teaching. Even followers of Anthroposophy often have difficulty grasping this fact, unfortunately. Rudolf Steiner himself saw and experienced this, and also spoke about it. In the written version of the lecture held in August 1908 entitled ‘Anthroposophy and Philosophy’, he says: “For, in its deepest aspects this (Anthroposophical – G.A.B.) movement will not achieve recognition in the world through those people who only wish to hear about the facts of the higher worlds; it will only come about through those who have the patience to work their way into a thought-technique which creates a real foundation for genuine activity, creates a scaffold (Ger. ‘skeleton’) for work in the higher world” (GA 35). These are the points of departure arising from the main principles of Anthroposophy, which we are here trying to research into and are striving to follow in our discussions. The phenomenon of thinking consciousness is, indeed, many-faceted. If we wish to investigate how it is dealt with in Anthroposophy, it is especially important to crystallize out its chief characteristics, from which then everything else proceeds and is illumined in a consistent and organic way. One of these basic characteristics is, unquestionably, the following: “The belief that the world is produced by thinking and continues to be so produced up to the present time, this alone makes fruitful one’s inner practice of thought” (GA 108, 18.1.1909). By ‘belief’ is meant in the present case that complex state of mind and spirit in which individual cognition, after the abstract stage of reflection has been overcome, merges together with the ideal, essential being of things. Belief then becomes a form of immediate, direct knowledge. Such a spiritual act has a thought-will nature; it is essentially unique; it is what humanity has been seeking for thousands of years.

The idea that belief represents, so to speak, a naïve state of the individual spirit, who gives up, and rejects, the attempt to understand the world through thinking cognition, is the fruit of human errors that have arisen in comparatively recent times and have in every case the same origin: the increasing split of the single, unitary world into the world of thinking and the world given to perception. In this connection the problem of belief became a problem of both consciousness and being. The following question began to play the decisive role: Can the human being understand himself rightly and come to a clear recognition of the significance of thinking for his own being? This question can be answered once one has grasped the fact that thought is a human being’s most individual possession, that which is most uniquely his own, while being at the same time of cosmic origin.

Anthroposophical theory

of knowledge teaches that the entire

consciousness of the world also lives in man,

but in an abstract form. Thanks to thinking, man

knows that he is also a spiritual being. But the

spirit that lives in us as knowledge is the same

as that which holds sway in nature. And in its

absolute nature it is the Holy Spirit. “All the

things around us,” says Rudolf Steiner, “are

condensed thoughts of God” (GA 266/1). These are

also nature-forces. The thoughts of God are the

laws of nature. As we raise ourselves to an

understanding of them, we grasp hold of objects

through our thinking. However, an object given

to perception is merely another form of its

spiritual essence or ‘ur’- phenomenon. We form a

thought by inwardly abstracting from the object,

the sensory form, and striving to grasp its

spiritual archetype: the natural law, the

‘ur’-phenomenon, the type; and finally the

‘I’-subject if we are dealing with cognition.

This is not a metaphysics of dualism. “The entire ground of being,” so we are told by Rudolf Steiner, “has poured itself out into the world, has become fully identical with it” (GA 2). It has not poured itself out into the special world of ‘otherness-of-being’, but into the world that is unitary in its being-nature and in which sensory being is merely one of the forms of manifestation of the universe. This is the universe of revelation, and it is centrifugal. The Godhead causes it to become centripetal, in order to return to Himself via the world; he does this by way of thinking which, in abstract form, constitutes the boundary of the universe (see Fig.37). From it the boundless, the absolute, is, so to speak, mirrored back; the inversion outwards gives way to an inversion inwards. This gives rise to a new quality of the world: It (the world) becomes knowable in the thoughts of man. Thus the universal foundation of being reveals itself in man’s thinking in that form which it possesses in and for itself. In the experience of perception it appears in a mediated form, which is authentic nevertheless. When we set up conceptual connections between things, the world-foundation itself is thinking in us; not as a force from ‘yonder sphere’, but as the real and immanent basis of things. Our judgment makes a decision about its own content. And this means that our knowledge is true. If we remain true to its essential nature and do not distort it with artificial constructions, then “not only must, where revelation is concerned, nothing be admitted for which no persuasive reasons exist in thinking; but experience must also become known to us not only from the aspect of its appearance, but also as an element that is actively working (‘in the original’ – N. Lossky)” (ibid.). When we think, we observe nature in its creative activity. Indeed, we see the things in the light in which our thinking, our cognition, illumines them. This question must be correctly formulated; then it will become evident that, while it is true that we look at things through the ‘spectacles’ of our subjectivity, their essential nature is only revealed when the thing is brought into connection with the human being. “We have knowledge of the world, not only as it appears to us, but it appears – albeit only to thoughtful observation – as it really is. The form of reality that is the result of scientific investigation is its true and final form” (ibid.). Such is the conclusion of Rudolf Steiner in the book in which he describes Goethe’s theory of knowledge.

Of course, if we are to overcome the antithesis between nature and spirit which can be experienced within the human being, we must approach it scientifically on many different levels. In the first place we must, in this case, take account of the fact that we have before us in nature as the immediately given, something that is conditioned; that which conditions it, we find in the spirit, to which we ascend through cognition. What is graspable by the cognizing spirit is also the cause underlying the things in nature. Spirit itself can, however, only be known in its conditioning activity; here the particular is an originator of laws and is individual. In science we have what is general or universal. The profound crisis of knowledge stems from the confusion of these things. But the confusion arose as a result of the increasing abstractness of thinking, its mechanical character, its formalization.

What Anthroposophy strives to do in this situation becomes particularly clear when we examine in more detail the nature of the primary and secondary qualities. The relation to them in traditional science has remained almost the same as it was in John Locke’s time: the view of the subjective character of sense-perceptions (secondary qualities) – the cornerstone of all unknowability – has not been shaken in the slightest degree; and the role of the “objective” definitions of the human mind has increased to some extent. Kant’s transfer of time from the ideal (thought) to the sensory category (the form of sensory perception – ‘Anschauung’) simply led to a worsening of the confusion in science (relativity theory in physics).

The nature of the primary and secondary qualities can only be grasped if we approach reality in its immediate ideal-real unity. As such, it is arrived at by the human being via two paths: namely, the percept and the concept. In the first case, it can be known indirectly, through the revelation of the form. But this mediation needs to be approached in the right way. An understanding of it must not be sought in the forms themselves – these are objective – but in the definitions of the human mind or spirit, through which the forms are described and characterized in quantitative terms. The form stands before us in unity with its content, though this can only be revealed through the cognizing mind of the human being. And it can therefore be said that, in this case, the essence of the things merges together to a unity with the cognizing subject. The essential (being) does not thereby become non-essential (Nicht-Wesen); it merely comes to expression in an abstract form that is void of essential being, though it is not itself an abstraction.

Thus the content of the form is itself seen to be a form: the form of the subjective, thinking human mind or spirit. It is a concept, or a totality of concepts, a system of definitions. And it becomes apparent that the form in which the content of sense-perceptible forms is revealed to thinking is itself a kind of archetypal form. In it are given to the thinking spirit the eternal laws of nature, which are identical with Divine revelation and with the Divine Essence itself. They reveal themselves to cognition when it permeates the world of experience with ideas. “In thinking we stand within essential being...”, as Rudolf Steiner remarked in one of his notebooks (A.22, 1929). The ideal definitions of the form of appearance are the multiplicity of concepts. The essential nature of the thing is unity, the idea. When we think, we become, within our inner being, partakers in the formative, creative substance or, more accurately, we partake in communion. Therefore in cognition we do not alienate ourselves from being; we form ourselves – within the ‘I’, as a constituent part of the world of being.

It is, first and foremost, the non-organic realm that we gain knowledge of with the help of the primary qualities. The ideal in it is not assimilated into the form, but works in it as a guiding force, governs it as a law of nature. The objects of the inorganic world work upon one another with the help of the laws that stand outside them. The original members of this category may be described as archetypal (or ‘ur’) phenomena. Here the ideal is present outside the perceptible manifoldness.

Of course, a second fact remains unaltered by this: there is nothing in perception that is not also contained in the concept. – This is one of the principles of Goetheanistic science. In inorganic nature there is a separation between ‘existing’ and ‘appearing’. In the human mind or spirit ‘existing’ comes to expression disconnected from the reality given in perception – a fact recognized above all by dualism. It rejects the idea that the form in which the phenomenon presents itself to our perception and the form of our abstract definitions of the object are two manifestations of one and the same natural power, the unitary spirit of nature. In the thinking consciousness of man, this spirit assumes the character of pure being, but because the thinking subject separates it from the perceptible things, with which it is in reality connected, it (the spirit) is robbed of its reality. But the human being becomes thereby in his shadow-like thinking a subject: the creator of the primary qualities of things. In this activity of his own, he restores to the things their ideal content, and together with this he also gives himself: he gives himself back to the universe as an autonomous new creation.

Darwinism was not mistaken when, in its study of the primary qualities, it gave central emphasis to knowledge of the emergence and transformation of plant and animal forms in the struggle for existence. But what it achieved was, of course, no more than a system of knowledge, which it was basically unable to unite with reality; the reality it was dealing with was, after all, life itself, whose secrets were not revealed to Darwinism. What is it that imbues form with life, brings it to metamorphosis and not only to quantitative change? The answer to this question is provided by Goetheanistic science.

Where organic nature – life in its varied forms – opens itself up to the cognizing subject, the ideal element in nature comes to direct expression with the help of the primary qualities. In the organic world, says Rudolf Steiner, “one single part of a living entity (Wesen) does not determine another, but the whole (the idea) conditions each single element from out of itself, according to its own nature” (GA 1). Thus the wholeness of the entity is the entelechy, of which we spoke earlier. When the human spirit wishes to gain knowledge of the organic, it frees the entelechy of everything that approaches it in the shape of chance external influences upon the organism, and reaches through to the idea that corresponds exclusively to the organic within the organism, the idea of the archetypal (‘ur’) organism, which Goethe describes as the type. “It is even more real,” Rudolf Steiner explains, “than any single real organism, because it reveals itself in every organism. It also expresses the essential nature of an organism in a way that is more pure and more complete than any single, particular organism” (ibid.).

On this level of being, the form of our cognition that is conditioned by natural law has little to offer. Indeed, can Euclidian geometry, for example, which is so necessary in crystallography, help us in any significant way in our study of plant morphology?* The unity of the organic world is higher than that of the inorganic – higher in terms of the developmental type. The forms of the organic world are the means by which the unity comes to manifestation. It is not so much the case that they spring forth from, as that they ascend to, a unity. It is particularly in research into the forms of the organic world that we apply the method of concrete monism developed by Rudolf Steiner. According to this method the forms must be explained with reference, not to the law, but to the type. To give an example: The forms observable in the emergence of a crystal and an apple have nothing in common. The organic fashions itself in the form, and not the form. The essential nature of the organic is something other than the manner of its self-realization in the form: The essential being determines the form in advance.

* We will not consider

here the esoteric aspect of this question.

_______

Of course, external elements exercise a certain influence on the formative process; they cause the form to change, but the all-determining factor remains the self-realization of the type, of the idea of the organism, of the entelechy as an active force. Its active working is direct, while outer influence on the living entity is indirect and no more than a stimulus.

In the study of organic forms, the concept is not a law standing outside the sensory manifoldness, it is the principle inherent in the latter. Here the sensory unity (of the organism) itself points beyond its own limits. The relation of its single members as a totality has become real, and it comes to concrete appearance, not only in our intellect, but also in the object itself, in that within the object it brings forth the multiplicity from out of itself. The idea here “is a result of what is given (experience), it is concrete appearance” (GA 1). Also, it reveals itself to the power of judgment in beholding. This power takes hold of the concept and what is given to perception, as a unity and shows itself to be, in the last resort, observation, though admittedly of a different kind than sense-observation. Rudolf Steiner calls it intuitive. Nikolai Lossky distinguishes between sensory, intellectual and mystical intuition. The circumstances surrounding them “are radically different from one another,” he says, “but in the final analysis all of them are, nevertheless, different aspects of the one cosmos which we grasp in thinking.”138 They all signify “the immediate beholding of the object by the cognizing subject.” But he emphasizes at the same time that “I do not mean by the word ‘intuition’ a seeing of the concrete, indivisible totality of beings: for, after all, even discursive, abstract knowledge can represent a seeing of the aspects of the most authentic being, when within being processes of separation and reconnection take place; in this way I can speak of the intuitiveness of discursive thinking, even of the intuitiveness of the understanding faculty (not only of the power of reason). On the other hand it is possible, especially if one proceeds from the doctrine of intuition as the direct beholding of being in the original, to explain cases of a seeing of the object in its organic concrete totality.”139

We are in a certain

sense summing up, in accordance with Rudolf

Steiner’s theory of knowledge, the concepts

through which the laws of the inorganic world

are manifested; but also – we would add – those

of the world of logic. The idea as a fruit of

experience “sums us up” ourselves, so to speak;

within experience it leads us to a higher

experience – to a beholding of the ideal

(world), whose first revelations already become

evident in our discursive thinking.

All secondary qualities address our power of judgment in beholding; they call upon us to overcome their character of sensory appearance and to cross the threshold separating the cognizing subject from super- sensible reality; i.e. they prompt us to make the transition from knowledge of reality that is mediated by form and concept, to direct knowledge of its essential nature in intuitive perception or beholding. What is observed by us in things is merely one part of them; the other part is revealed to the cognizing mind or spirit, directly. “Only when we hold together the language of the outer world with that of our inner world do we have the full reality,” says Rudolf Steiner, and continues: “What did the true philosophers of all times want to do? Nothing other than to tell us of the essential nature of things, which the things them- selves proclaim when the spirit lends itself to them as an organ of speech” (GA1). Let us illustrate these points with the help of a diagram (Fig.66). This will also help us as we build up the thought-structure that follows.

2. Some Special Features of Quality and Quantity

When the cycle of primary and secondary qualities experienced by the human being draws together within him to form a single whole, the antithesis between subject and object is overcome. It grows clearly apparent to the human being that nature itself is speaking through his cognition; it is active in his thoughts and attains completion through them. All of this becomes especially easy to grasp if we turn our attention to beholding. Reality cannot be derived from the mere intellect. Our task is entirely different, namely: How can one endow the intellect with reality and, as a next step, the human being with essential being, thus making him into a true subject? To attain this goal we must (according to Fig.66) unite the concept with the percept and come to a living experience of thinking in the sphere of the secondary qualities. Then thinking acquires its own morphology: in it the idea becomes type and essential being – it becomes life of consciousness, thinking will, individual ‘I’.

Natural law (the ‘ur’-phenomenon), the entelechy (the type), the self-conscious ‘I’, which rises to the higher ‘I’ – in these three form- principles the ideal world undergoes its evolution. In natural law idea and reality are separate. The type brings them together in essential being. In human consciousness the concept becomes an object of perception. Here, beholding and idea coincide. The ideal world becomes beholding. Thus, the hidden ideal core of the nature surrounding the human being – of which he himself forms a part – comes to manifestation in the lower-higher ‘I’.

However, in the thoughts we are putting forward here there is one aspect which could be subject to serious criticism from the standpoint of physics. The following objection could be raised: If, for an understanding of the living world – also in the sphere of thinking – it is essential to behold the supersensible within the sensible, how is it with our perceptions of light and colour, which are secondary qualities of things, but reveal themselves nevertheless in inorganic objects? This objection has its roots in the Kantian, a priori principles of sensory perception, which are incorrect and served as a basis for the materialistic direction in physics, where the qualitative side of reality was replaced by the quantitative. To what outcome this led in practice has been discussed in the fourth chapter of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’.

In his philosophical system Kant postulates four categories which – as opposed to Aristotle, whom he unjustly accuses of nominalism140 – he firmly believes have been deduced by him with strict scientific necessity. These categories are: quantity, quality, relation, modality. Each of them comprises its own class of concepts stemming from the understanding faculty, some of which Kant – following Locke in this case – describes as mathematical, and the others as dynamic; to the second group belong: reality, negation, limitation.141 Among the dynamic concepts Kant also includes time.142 Similar to the Kantian view is that of modern physicists, when they say that the qualitative only arises as a result of the working of the quantitative upon the sense-organs; red is distinguished from blue only through the vibrational frequency, i.e. through a process of movement. A similar shifting of concepts takes place in abstract thinking. This fact is of crucial significance for an understanding of the meaning and the mission of science.

In contrast to materialism, the Goetheanistic Anthroposophical teaching with regard to the nature of sense-perceptions begins where physics ends. Here the wave-theory of light is viewed as an attempt to derive the phenomenal states of life from non-organic forms – i.e. to introduce a strictly determined causal connection into the sphere of the life-processes, “to test harmony by means of algebra”.

For Newton light is a composite phenomenon, whose elements are simple colours. Goethe considered this way of thinking unjustified. He regarded light as an indivisible, homogeneous being, as the simplest of all those known to us. Colours arise within the light; they are its “deeds” and its “sufferings”.* But the essential being of light is immediate, and thus it appears for observation. To paraphrase Kant: Light, but not time, can be viewed as a pure form of sensory beholding, because of its indivisible nature.

* We would note in

passing that those are the seventh and eighth

categories of Aristotle.

______

Philosophers of a certain kind maintain that

behind the appearances of the sense-world lie

its original, unknowable elements; light is,

they say, such an element, a simple entity

resting upon itself and not derivable from

anything else. In order to assess this opinion

correctly, one must of necessity base one’s

inquiry on the phenomenological method developed

by Goethe for the study of colours. This was

described very well by Goethe, and a commentary

was written by Rudolf Steiner, in which further

aspects were added; we will therefore do no more

than indicate its most important assertions.

According to one of them, darkness

forms the

opposite pole to light, and there is interaction

between these two. It is from this that colours

arise. For example, yellow is light that has

been diminished by dark; blue is darkness that

has been mitigated by light.* The darkness of outer

space is changed into dark blue sky by the

illumined cloudedness of the atmosphere. At

sunrise and sunset the light – depending upon

the degree of cloudedness of the atmosphere –

passes from yellow to orange, and even to ruby

red, etc.

* In all this we have to

do with facts that are experimentally verifiable

with the help of a system of prisms, light

filters etc. In Middle Europe excellent courses

and lectures are held accompanied by

demonstrations of the data that are obtained

through experiment, where conclusive proof is

given of the correctness of the Goethean

phenomenology with regard to light and colour.

Andrei Beliy in his book ‘Rudolf Steiner and

Goethe’ is, so far, the only Russian to have

seriously discussed this subject.

_______

Goethe’s views on the

nature of light do not contradict in any way the

conception of the relation between light and a

certain process of movement in space. As Rudolf

Steiner explains, Goethe only insists on the

following: “The qualitative elements of the

sense of vision: light, darkness, colours must

first be understood within their own context and

be led back to ‘ur’-phenomena; then, on a higher

level of thinking, one can investigate the

relation that exists between this complex of

facts and the quantitative, the

mechanical-mathematical in the world of light

and colour” (GA 6). In this case, too, the

conception of a movement is untenable which is

not given to experience, but is merely a form of

thinking, a mathematical thought-picture which

supposedly determines reality.

The qualitative is unquestionably present also in the outer world, constituting there an indivisible whole with space and time. The physicist’s task, says Rudolf Steiner, is to lead back complex processes in the realm of colour, sound, warmth phenomena, magnetism etc. to simple processes within the same sphere. In his application of mathematics the physicist must not equate colour and light with phenomena of movement and force; he must seek the relationships within the phenomenon of colour and light. Therein lies the mathematical method in physics.

The quality ‘red’ and the given process of movement constitute a whole. They can only be separated in our intellect, but then it becomes evident that there is no reality underlying this process of movement. It exists in the same way as, in abstraction, a cube of the salt crystal exists, but it is not possible for us to form a real salt crystal out of a mathematical cube. Correspondingly, no colour can be created out of the wave-movement of light, just as little as all the discoveries of quantum mechanics enable us to create an atom.

Quantity as such does not create quality. It is incorrect to think that primary qualities, as form-conditions, give rise to secondary qualities – life-conditions. In reality the situation is exactly the opposite. The secondary qualities are substances of a purely spiritual nature – thought- beings. The same is true of light. “Inwardness,” says Rudolf Steiner, “must be seen as an attribute of light. In each point within it, it is itself” (GA 130, 1.10.1911). This can be regarded as the fourth dimension. Light is present wherever there is sound and warmth (cf. 5.12.1920). It is also the causative factor underlying the sense of sight. Goethe says in the introduction to the didactic section of this theory of colours: “The eye owes its existence to the light. Out of the rudimentary accessory organ of the animal the light calls forth an organ that is to be akin to its own nature, and thus the eye is formed in the light and for the light, so that the inner light may come forth to meet the outer.”143 This is the objective character, the objectivity, of the phenomenology of the secondary qualities.

The thoughts of Goethe and Rudolf Steiner concerning the nature of the secondary qualities have their roots in esoteric Christianity; it cannot be otherwise. Only an entirely superficial mind can look upon the words at the beginning of the St. John’s Gospel as a metaphor: “In Him was life; and the life was the light of men.” This statement must be taken literally, when it is applied to the Goethean colour theory.

In the light, the spiritual light in particular, the morality of the world is revealed to the human being. When spirit densified to matter, the light was reflected back from it. The bearers of the light of Christ are the Elohim, the spirits of Form, who bestowed the ‘I’ upon man in the aeon of Earth. In the reflected light of the sense-world Luciferic beings are revealed. Light is human thinking, which therefore has two sides: the reflected, Luciferic, abstract side, and the aspect of essential being, where consciousness and being constitute a unity – a unity of form, movement and quality.

In the course of the creation of the aeons, as described by Rudolf Steiner, the sacrifices brought by the higher Hierarchies spread out in the form of “sacrificial smoke” (of a spiritual kind, of course) from the centre of the universe to its periphery, where the beings of the third Hierarchy acquired the ‘I’-consciousness. This “smoke” was reflected back by them as light. On Old Saturn the second Hierarchy revealed itself in the light, but there was as yet nothing that it could illumine; on the Old Sun the Archangels breathed in the sacrificial smoke (cf. Figs. 11, 13, 14) at the periphery of that universe, and breathed out light; on the Old Moon colours appeared in the reflected light.

In the aeon of Earth the human being, who stands at the periphery of the universe, reflects its working in the form of light-filled thoughts. This happens in such a way that the universal beings directly and objectively appear to him. And he himself (not only his eye) is a creation of these appearances. And in philosophy, as we already noted, Kant had a partial inkling of this spiritual impulse behind thinking when he described his a priori principles of sensory experience as transcendental aesthetics. He could equally well have called them transcendental ethics; we will be speaking of this in our further discussions of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. These pure senses are objective, and the fact that they are experienced by the human being does no more than reflect the other side of their unitary nature. For it is in aesthetics and morality that the antithesis between object and subject was first (and continues to be) overcome; they united within themselves the universal and the individual and created the pre-conditions for ‘beholding’. Thus Goethe, who combined in himself poetry and science, was able to realize the intellectus archetypus.

“Ethics (also aesthetics – G.A.B.) is... a doctrine of what is (vom Seienden),” says Rudolf Steiner (GA 1). In it are revealed the secondary qualities of things, including those of the subject himself, and they stand higher than the sensory perceptions conveyed by the sense- organs. One can describe them as pure being, as they are the revelation of the world-soul (see chapter 1, 6), of universal life, of the Word, of the second Logos, the Christ. In Christ the true beauty of the world is revealed. Being which contains mediation – to employ the language of Hegel – is thinking, pure abstraction. As existence it is form and quantity, “determinate quantity”. Hegel speaks of this as follows: “Quantity is pure being in which the determinacy is posited, no longer as one with the being itself, but as superseded (aufgehoben) or indifferent.”144 Also: “The (determinate – G.A.B.) quantum is the existence of quantity....”145 This is the nature of all that is created through the abstract activity of the understanding, including the categories of quantity itself.

Let us now, with the

help of a diagram (Fig.67), draw together into

the unity to which they belong, the many aspects

we have discussed. Then all that we arrived at

in Figs. 20 and 66 will reveal itself to us in

greater detail.

3. What is the Relation between Thinking and

Being?

The picture shown in Fig.67 bears a relation to the human being of the future, who has already acquired the ability to carry out free actions, the necessary prerequisite for which is that he has become a being who evolves in his ‘I’. Freedom of action presupposes development of the free individuality, and the latter presupposes an understanding of the idea of freedom. The human being of today has attained this insight only to a minimal degree, although it is precisely here that the central meaning of his existence lies. He would already go a long way, if he could only understand the following: The world of secondary qualities, which is revealed in sense-perception, cannot be known in its essential nature in abstract conceptual terms. “Just as the eye is the organ for perception (not for understanding - G.A.B.) of the phenomena of colour,” says Rudolf Steiner, “so what is needed for an understanding of the living realm is the ability to behold directly a supersensible reality within the sense-world” (GA 6).

The only real things in

the universe are subjects – everything that is

endowed with an ‘I’, whatever may be the form in

which it realizes itself. Its forms can be

grasped, its life can only be ‘beheld’. The life

of the ‘I’-beings pervades the world with its

vibrations and enters into the human soul, in

order to express within it their true nature. It

is in this way that the life of thinking arises

in the human being. Over against this life

stands the ascendancy of form. Its spiritual

content is poured into the world of our ideas,

but it cannot communicate to us its life, all

the more so because it is itself continually

losing this life as a result of its own tendency

to rigidification and immobility. It is

therefore necessary for human consciousness

itself to gain possession of life (Fig.68). Such

are the laws of evolution.

Originally, it is by way of perception that life enters the consciousness of man, but his spirit is blind to this perception. On the other hand, he is awake to those ideas of world-consciousness which arise within him thanks to the sensory perception of the forms through which this consciousness reaches him indirectly. World-consciousness is objective. Through bringing its two modes of appearance to a unity within him (in inner representation) the human being gains in two respects: He acquires a subject within himself, and restores the unity of the world in the realm of appearance: he gives back the ideas to the revealed things in the world, which in turn creates for them the possibility of becoming subjects in the future. Through reflecting upon the forms of his own consciousness, he gives the Divine quality even to his abstractness. The form of existence of the abstract mind is like a mineral. Its law (logic) stands outside it.* The difference between the abstract mind (Geist) and the mineral is that the former is endowed with an ‘I’ – albeit one that is without substance – directly within sense-reality. For this reason it is possible for the ‘I’, after a change in its method of thinking, to instill life into its “mineral” of consciousness, without having to await the occurrence of world-wide metamorphoses.

* “Thoughts are just like

mirror-images: they do nothing, they are not

impelling in reality” (GA 224, 21.6.1923).

_________

The realization of this is hindered by

philosophical doubts in the human being. Even if

he has overcome solipsism and naïve realism, he

still asks himself such questions as: Why is the

world given to us in inner representations not

enough in itself? Is the necessity to reflect

back this world in concepts entirely objective

(from the standpoint of the world-process)? Is

it a necessity of this same world, the universe,

that we reflect it back?

Let us turn to the introductions and commentaries on the natural-scientific works of Goethe, written by Rudolf Steiner. He remarks there, that cognitive activity only has a meaning if what is given to us in perception is not the whole reality but only a part of it, and if one contains within oneself the other part, as something higher that cannot be perceived with the senses, but only spiritually, thanks to the human being’s capacity to think. Hence, thinking adds nothing to reality, but merely – like the eye and the ear – perceives that within it which has the character of an idea.

Kant, Schopenhauer and

the neo-Kantians maintain that ideas have no

content of their own, that the idea and the

object of beholding (the percept) are congruent

with one another, that the idea is nothing more

than the counter-image of the beheld object. But

Rudolf Steiner suggests that we ask the

following: How is it that we are able to clothe

a multiplicity of percepts in a single,

indivisible concept? An infinitely large number

of human beings perceive an infinitely large

number of trees. All their percepts are

different, as the subjective element is

contained within them. And yet, the concept of

the tree is, for all of them, one and the same.

Something similar happens in the realm of the

abstract. Here we can think of the multiplicity

of different triangles, a multiplicity which

does not alter the fact that there is only a

single general concept: “triangle”. From this it

follows that the concept, and still more so the

idea, has its own content, and therefore concept

and percept (object of beholding) are

not initially congruent with one another. They only become so

in the inner representation – i.e. in the

subject.

Beholding (percept, observation) always contains the particular and is, therefore, multiplicity. Even when we look twice at the same car driving past, we perceive it each time differently. But the universal – the concept “motor car” – is not impaired by this in any way. Rudolf Steiner asks: Can the unity of the concept be broken down into a per- ceptual multiplicity? – No, this is not possible. The concept has no knowledge of the particular, as the latter is only perceivable and not conceivable. The elements of multiplicity are given in perception. Thus concept and percept (object and beholding), while “in essence the same, are nevertheless two different sides of the world” (GA 1).

Thanks, therefore, to the activity of perceiving, of observation, the concepts are called forth in us. The conceptual universality in which concepts have their essential content is only to be found in the cognizing subject. It is obtained by the subject in connection with the object, in confrontation with the object, but not out of the object. When it arises, it has to give itself a content that is different from the world of sense-perceptions. This content works as a principle which activates the process of perception, i.e. it is qualitative in nature. We observe the objects passively; here we need do no more than use our sense-organs. The concept is the fruit of a spiritual activity. When we perform this activity we begin to understand that which remains inaccessible to perception: The driving forces of the world and the principles of its development. That they are real, of this there can be no doubt. In this case, however, the question mentioned above – Why do we need to reflect back the world in concepts? – can be preceded by another, or we can at least add a missing part to it. The resulting question would then be: If the part of world reality that is given to us in thinking is not essential, why did the world have to reveal itself to man in percepts? – That is to say, if cognition is not able to add anything to the content of the world, then perception – so we are forced to admit – can give the world still less. And in this case, to remove the human being from the evolution of the world will make virtually no difference to it. If, hypothetically, we remove one of the natural kingdoms – so one can argue in this case – we fundamentally change thereby the total picture of the world and its evolution, but if humanity were to disappear (or had remained behind at the animal stage), everything would remain just as it was before! If they are consistent, this is the conclusion which must be drawn by all those who underrate the importance of thinking and cognition in the objective evolution of the world. From this position it would follow that the human being is unnecessary for the world, not only in his scientific experiments, but in any role or characteristic whatever. Such are the conclusions drawn by cognition in the final stage of this crisis. That they are remote from reality (lebensfremd) and therefore life-destroying needs no proof, but is purely and simply axiomatic.

Because it takes account of the reality of life, Anthroposophy teaches how one can return to the reality of what is grasped by the intellect. It places a truly immanent world view over against the transcendentalism of sensualism and agnosticism and the metaphysics of dualism. The differences here, as defined by Rudolf Steiner, consist in the following: The foundation of the world, which the transcendentalists and metaphysicians seek in a ‘world beyond’, which is foreign to consciousness, is found by the immanent world-view in “that which comes to manifestation for the faculty of reason. The transcendental world- conception regards conceptual knowledge as a picture of the world. Thus the former can only provide a formal theory of knowledge, based on the questions: What is the relation between thinking and being? The latter world-view places at the forefront of its epistemology the question: What is knowledge? The first proceeds from the prejudice of an essential difference between thinking and being, the second focuses in an unprejudiced way on the only thing that is certain, and knows that no being is to be found outside thinking” (GA 1).

When the world of percepts appears before our thinking consciousness we give it the opportunity to address our power of judgment, whereby we hope to arrive at objective knowledge. Then a certain organ starts to become active within us, to which the second half of reality is revealed. Only when we have acquired both halves do we experience satisfaction with the world-picture in our consciousness. Now the perceived world stands before us in its “original form”. In appearing to us it performs its final deed. When we think about the world of percepts, we begin a process which cannot come about without our active participation; we take fully hold of this process and imbue with it the panorama of percepts which stands before us with all its riddles. Then the percept becomes for us as transparent as the thought. From this it follows that “a process in the world... (shows itself to be) entirely permeated by us, only if it is our own activity. A thought appears at the conclusion of a process within which we ourselves are standing” (ibid.). Thought reveals to us that part of reality which cannot be taken hold of with the lower sense-organs.

From the evolutionist position we have shown how and where this part of reality comes into being (see Figs.14 and 23). We experience a certain periphery or boundary of the universe when we have started to reflect. But reflection is not an empty mirroring; there lies within it the beginning of the return of the subject to the primal source of being. In the process of development this primal source brought about an extreme form of densification. Every substance, says Rudolf Steiner, is actually a concentrated, densified world process (see GA 343). For this reason, the universe that is given in percepts contains within it the entire mystery of world evolution, and there is therefore nothing spiritual that does not manifest in some way or other within sense-reality. The human being is a product of nature, but over and above this there has developed within him the capacity to experience the sensory phenomenology of forms and also of life and of consciousness – a capacity that is not even given to the Divine beings of the Hierarchies.

4. The Divine and the Abstract

We can imagine what is shown in Fig.23 as a kind of cosmically all-embracing “outbreathing” of the universal Being, whereby the latter, too, breathed itself out, identifying itself in this process with the multiplicity of phenomena created through its outbreathing, as the entities of which the world is constituted. At the outermost periphery of this “outbreathing” a creation gradually emerged, which had the capacity to draw the manifoldness of phenomena back into an ideal unity. Thus the universal Divinity is given the possibility of beholding Himself, so to speak, through the human being, of objectifying Himself within Himself. In the evolution of the world this was present from the very beginning as the aim and the law of its development, which led to the forming of the ‘I’-consciousness in man.

We discussed earlier how, before the beginning of the evolutionary cycle, in the Great Pralaya preceding it, the First Logos reflects itself, as it were, within itself, and in so doing imbues with life its own all- consciousness outside itself, in its reflected form. Thus arises the Second Logos. The unity of the world has since been preserved within the First Logos; through the activity of the Second Logos within creation, consciousness and life gradually strive to go their separate ways, attaining their extreme antithesis in the human being. In order to lead such a “periphery” of the world back to the unity of the Father, the Son had to make the greatest of all sacrifices: He had to descend into the realm of otherness-of-being and show man the way “to the Father”, to the unity of consciousness and life. The unity of the rest of the universe exists in the Father; it is forever unchangeable, but without individual human self-consciousness. When Christ went through the suffering of the Mystery of Golgotha he restored in the human being the unity of consciousness and life. God also became immanent to the individual spirit of the human being, only this fact requires, because it is rooted in the ‘I’-phenomenon, free recognition and acceptance on our part. This is the manifestation of the supernatural character. There is a notebook entry of Rudolf Steiner stating that the proclamation of the Second Logos is as follows: “I am All”; while the all-consciousness of the unity of the Father may be defined as “All is All” (GA 89).

Rudolf Steiner was emphatic in his defence of the point of view that there is no God standing above the world; God has poured himself fully into the world, but not only, of course, into its sense-perceptible aspect. He became immanent to the world in its unitary, sensible-supersensible reality. This consists of various levels, and God is present on them in different forms. The immanence of God in the world of the Hierarchies, of mighty ‘I’-beings, comes to expression in the fact that they are high creative Beings. The immanence of God in created nature is of a different kind.

The immanence of God in the world comes to expression in the fact that the world as a whole is an individual and the personification of the ‘I’-consciousness in it is its members (see Figs.17, 25 a,b,c). This individual continues its process of becoming, which is not completed within the confines of the evolutionary cycle. The human being bears his ‘I’-consciousness within himself, but there is no life in it.

If the human being knows the natural law, the ‘ur’-phenomenon, the type, the ‘I’, then he knows God in the world; he knows the essential being of the world, which is spirit, and this reveals itself in thinking in the form of concepts and ideas. In the beholding of ideas man experiences Divine revelation.

The best minds of German idealism, including Kant, wrestled with the question: How can one transform the truths of revelation into truths of reason? Anthroposophy has given the answer to this question. “To investigate the nature of a thing,” Rudolf Steiner says in the article ‘Goethe’s Theory of Knowledge’, “means to take one’s start in the centre of the thought-world and work from this point, until a configuration of thought arises before the soul which shows itself to be identical with the thing we have experienced. If we speak of the essential nature of a thing or of the world altogether, then we can mean nothing other than the comprehending of reality as thought, as idea” (GA 1).

In this sense the idea is One, while concepts form a plurality. The Idea said of itself in the burning bush to Moses: “I am the I AM.” It is here that monotheism and polytheism have their origin. The ancient peoples experienced the spiritual world as a multiplicity of thought-beings. In Christ the unitary essence of the ideal world poured itself into the physical plane. Therefore Christ said: “I and the Father are one”; at the same time, Christ is the life of the world. Hence, so Rudolf Steiner explains, to experience oneself as a Christian means: “To let the world-thoughts be crystallized out etherically in one’s own ether-body. And in addition to this, one must think in accordance with the world-will, i.e. one must surrender one’s own will in the astral body astrally to the world-will and thus recognize the Logos in Christ, so that the Christ becomes creative (in us – G.A.B.) (A.3, 1928).” Such is the esoteric side of thinking and the inner technique of the transition from abstract thinking to the thinking that is permeated with will, to thinking in the substantial ‘I’.

* * *

Abstract thinking is bound up with the life of the nerves, with the head. The ‘I’ of abstract thinking is hostile to the laws of life, as it is unable to transform substances. Consequently, in his nervous system, his head, the human being falls out of the universe. Aristotle was already beginning to experience this process. In Roman times the abstract became so strong, that it led to the concept of the rights of the citizen. The state of non-being in thinking gave the human being the feeling that, in the universe, a space was thus opened up, to which he and he alone was entitled. Initially this – so we may call it – “strange” form of selfhood arose on the basis of the death-process in the physical body; yet it is not illusory, because it is able to activate the individual will.

The results of abstract thinking are twofold. The first is that the abstract ideas, by way of processes in the physical body which arise in the act of thinking, also work upon the etheric body (the life-processes), on the will-elements, and give rise to actions that are by no means always in accord with the experience of our perceptions. This thinking is ego-centric and one-sided; only with the greatest caution should it be applied to the practical life. To characterize it, one could say: it lets itself be guided by individual sense-perception, and is able at the same time to discount the role this plays; it rejects the spirit and, in the end, reflects only what sense-perception arouses in us. In short, it is anthropomorphic, but in the negative sense of the word: it is conditioned to a large extent by what is instinctive. In its lack of substantiality it also contributes to the partial release of the ether-body (due to the dying of the nerve-cells), particularly in the head region. This is the second result, which can be made use of for positive purposes: When he thinks abstractly, the human being is engaged in a spiritual existence, even if he dismisses this fact.

Every thought, even the most abstract – says Rudolf Steiner – has its counterpart in the spirit as a spiritual being. This being also shapes the substance of the thought. In us, only its imprint appears, and this imprint of the spiritual being “is what we call an abstract thought” (GA 93a, 12.10.1905). Such a thought is, for example, “pure being”. For the philosopher it is “the imprint”, but in reality it is the being of the intelligible world, unrelated to the sense-world.

Indirectly, in images (imprints), there is given to human consciousness all the being of the world-consciousness which works in the evolution of the world as the totality of spiritual beings. The human being began to live consciously in abstractions during the epoch of the Old Testament. It was then called “living in the law” (see GA 186, 7.12.1918). This life in the law had a religious-social character and was still bound up to a greater extent with the rhythmic than with the head-system of man. In more recent times, particularly from the 15th century, abstract thinking took hold of the entire human being.

In antiquity the specific character of abstract thinking came to expression in a very marked way in Plato’s ‘Republic’. In our own time materialistic science, mathematical logic, computer “thinking” are developed with the help of abstract thinking. But also the entire sphere of social life, the structuring of society and production, are realms which the human being is striving to organize on the basis of abstract schemes of thought. A spirit of this kind does, indeed, have (in the Marxian sense) a “superstructure” character in the human being and merely reflects the laws of the inorganic world. The doors to the ‘ur’- phenomenal in the world, however, remain closed to him. He stands as a stranger towards the living realm.

* * *

World-consciousness is a reality. In one of Rudolf Steiner’s note- books there is an interesting thought concerning the principle of its working in the human being. It runs as follows: “The mental representations gained from the sense-world should not be applied to the inner human sphere, the spiritual. The spiritual beings should not come to the human being from outside .... One should only enter into a relation with the spiritual beings inwardly (in thoughts – G.A.B.) Spiritual beings who come from outside pursue their own, and not human aims” (let us say, in natural laws, in the evolution of species – G.A.B.).

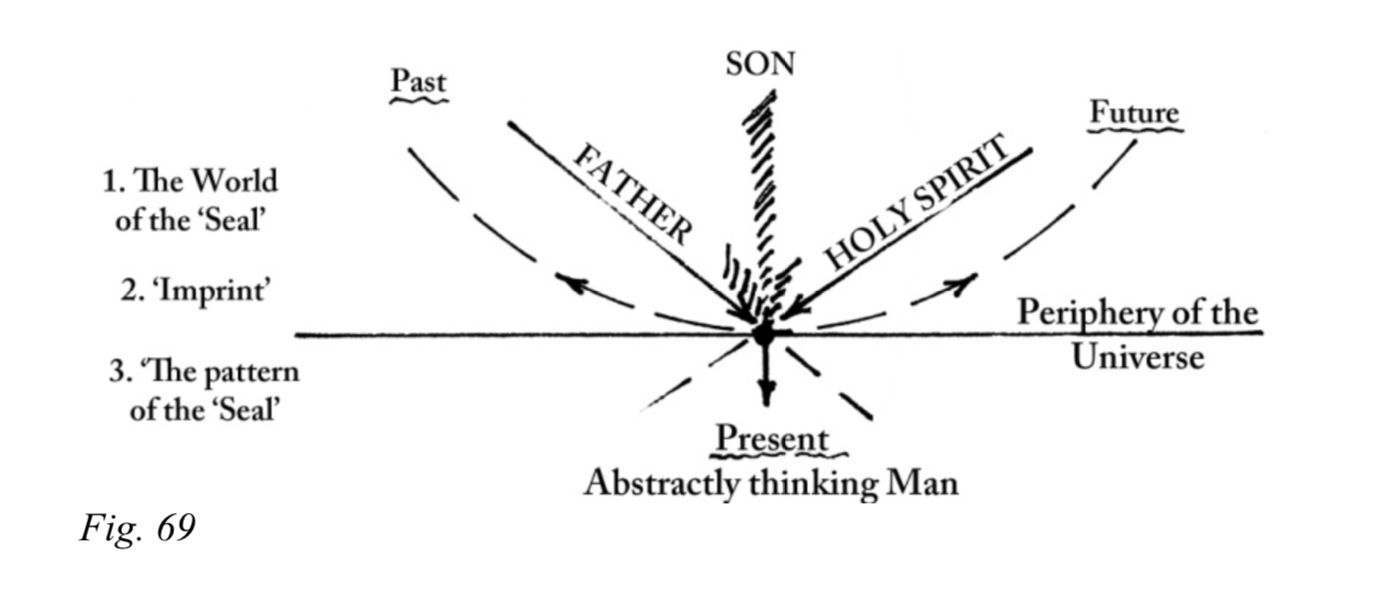

The theme of these

notes is actually the primary and secondary

qualities, and it harmonizes with what we said

in chapter 1 about the primal revelation of the

Father. When it has become evolutionary process,

this revelation works in the direction from the

past to the future. Working in the opposite

direction is the Holy Spirit, who reflects back

to the Father what has been received by the Son.

Out of the interrelation between Father and

Spirit arises the multiplicity of forms. They

densify to the material state and form a kind of

“funnel of evolution”, which the human being

also “slides down into” when he severs his ties

with the spirit but receives instead the

object-oriented consciousness (Fig.69).

At the periphery of the universe the human being is indeed approached from outside by the spiritual thought-beings whose aim it is to lead His revelation back to the Father – i.e. to bring the world to completion within the Divine Tri-unity. In their deeds, says Rudolf Steiner, “the self-revelation of Manas (i.e. the hypostasis of the Holy Spirit – G.A.B.) is ... the law”, and they do in fact have, in a certain sense, their “own” aim. Its imprints are known to us in the form of natural laws, which have nothing to do with the human being: “The law saves the world, but not the human being” (GA 343).

Spiritual beings guide the objective evolution of the world, bring about metamorphoses in it, densify and spiritualize aeons. In this activity of theirs the human being is, so to speak, a “by-product” – above all in the element of the lower ‘I’; this is why the materialists who regard the ‘I’ as a mere concept can also not understand what is the meaning of human existence. Its nature is twofold. As the fourth natural kingdom the human being is a component part of the system of nature. But as the fifth kingdom, the kingdom of the spirit, of freedom, of moral intuitions, the human being acquires his meaning in relation to the Christ. He begins already to develop this relation in the abstract sphere (a particularly striking example of this is Hegel’s ‘Philosophy of Religion’). The abstract thinker has the tendency to generalize (Ger. ‘universalize’). And as the laws of nature are immanent to the sense-world, their reflection in thinking consciousness brings about the universal immanence of thinking consciousness in the world of nature. But the abstractly thinking human being alienates himself from the essential being of what appears to the senses, and nature cannot give back to him this essential being. Christ alone can do this: He can give life to the consciousness that thinks in ‘beholding’, and together with this He can give a universal meaning to the human individuality. The human being, who has lost this meaning in accordance with the laws of development already known to us, was drawn by natural necessity to identify with the forms of being – right down to those in which the spirit dies. This shows itself in the fact that he focuses the entire force of his intellect on working upon sensory reality; and as he does not understand that, in the lower ‘I’, it is not yet granted to him to transform this reality in its essential nature, he places it in the service of his non-spiritual needs; he begins to consume with the fanaticism with which in earlier historical periods he prayed.

Rudolf Steiner says that the animal, too, is pervaded with abstract concepts. These work in it as a special instinct, thanks to which the wasps, for example, “invented” paper long before the human being. Out of the observation of a multiplicity of dogs, the human being crystallized out the general concept “dog”. But it is in the dog’s nature to be governed by this concept, and consequently he is unable to distinguish himself from other dogs. It should come as no surprise to us that the abstractly thinking human being increasingly has the wish to live like his “beloved animals” and only think of food. It was to this end that he transformed his abstractions into machines. For Hegel the individual human being who constructs objects for practical use – a carpenter, for example – is abstract.

In order to take complete command of his own reality, the human being must fill the reflective spirit of thinking with spiritual content. Before a true beholding arises, he must enrich the world of intellectual concepts with spiritual knowledge, knowledge of the fact that spiritual beings stand behind the forms of the sense-world. In order to be able to reach through to them the curtain of the outer senses must be overcome, and this requires metamorphosis of the instrument of cognition: from abstract to pure thought that is not dependent on the physical bodily nature.

When the human being thinks, not he but only his image exists. This gives the foundation for the principle of freedom. Freedom itself is attained in pure thought as transformed selfhood. The intellectual life of thinking is the life, now extinguished, of feelings and perceptions to which in ancient times, albeit ill-defined and unindividualized, vision of the intelligible beings was revealed. In our time the necessity has arisen to re-enliven dead thoughts with feeling – but now on an individual basis – transforming them into higher, pure feelings: and as the next step to identify them with the will. It is in this way that the Son leads the human being to the Father. Corresponding to this, the world-Spirit then reveals itself to us differently – not at the periphery and in reflection but, similarly, on the path to the Father, in that we receive teaching (as from Sophia) concerning the Son – the true Saviour who came from without, through the curtain of the outer senses, in order to enliven us from within.

* * *

The unity of man and world can be understood as the unity of man and God. This unity is dynamic and evolutionary. Actually, the process of cognition is also one of the stages of evolution – the last on its path leading from the spirit to matter. The law that dominates here consists in the fact – as described by Rudolf Steiner – that “it is in the life of the surrounding world that independent being is first separated out; then in the being thus separated the surrounding world imprints itself as though by a process of mirror-reflection (emphasis – G.A.B.), and then this separate being develops further independently” (GA 13). Also subject to this principle is the evolution of consciousness, which is already now taking place on an ascending stream moving from reflection to ‘beholding’. The mirroring character of thinking can also be seen as a method of separating oneself off, of severing oneself from the “surroundings”, which for the spiritual human being is the group form of consciousness. A genuinely independent development, however, is only possible for the human being when he has attained ideal perception.

‘Beholding-in-thinking’

once more acquires a pictorial character, as the

spiritual world which surrounds the human being

consists of thought-beings who possess a

‘Gestalt’ – i.e. form and image. Everything they

create has a picture quality. Rudolf Steiner

says: “For everything is created from pictures,

pictures are the true causes of things, pictures

lie behind all that surrounds us, and we dive

down into these pictures when we dive into the

ocean of thinking.... These pictures were

referred to by Plato.... Goethe was referring to

these pictures when he spoke of his archetypal

plant. These pictures are to be found in

imaginative thinking” (GA 157, 6.7.1913). In

imagination the human being has experiences

which in many respects resemble those arising

from sense-perception. In it there is a return

to the old principle of mirror-reflection as a

relation in which substantial

unity prevails.

A similar relation, albeit in a coarsely

materialized form, occurs in the assimilation of

food and in breathing. Sense-perceptions are a

refined form of breathing.

In the aeon of the Old Sun warmth-substance in their surroundings streamed into the human monads and out of them again, which was like a dim perceiving in which the breathing and nutritive processes were also contained in a germinal form. On the Old Moon breathing and nutrition are already separate, but they remain similar to one another. In the human astral body, which is not yet individualized, they give rise, in germinal form, to sensations and feelings. Through the relation to the surrounding world, the spiritual world also made its entry into the human monads, let its picture-forming activities stream into the human being and held them back in reflected form. Through these mirror-reflections of the spiritual pictures the human being was formed from within, whereby he himself became their mirror-reflection. This was how picture-consciousness arose in the human being. At that time the process of inner representation was close to that of reproduction. Later these two separated, when inner representations had begun to establish themselves supersensibly in the human being. And all these processes, which led gradually to the building up of homo sapiens in the totality of body, soul and spirit, are striving to undergo metamorphosis in the point of his individual ‘I’ and, as they cross over “to the other side”, to be repeated within the being of the thought-entities of the individual human spirit.

* * *

The world was not filled with pictures from the very beginning. At first the universal Being, which possessed the highest degree of selflessness, simply poured out its being into the world. This was the First Logos. In pictures, the Second Logos poured itself out into the world, filling it with pictures, colours, light. The Third Logos let its own being resound selflessly throughout the whole world, and the First and Second Logos resounded together with it (see GA 266/1). Of this, it says in Genesis: “The spirit of God moved upon the waters”, that is to say, pervaded with its rhythm the emerging world; then the following was spoken: “Let there be light: and there was light.” Thus the First Logos objectified itself, which for the hierarchical beings meant that they came into possession of the picture element. All this began to take place in the aeon of Old Saturn.

At the present stage of development the highest processes and phenomena of the past have led to the situation where the human being – the “image of God” – has entered into a relation with coarse matter by way of nourishment and breathing. On a finer level he breathes and feeds himself with spiritual air and nourishment: namely, when he forms inner representations and has religious and aesthetic experiences. And it was only in abstract thinking that he stopped breathing in any way at all; thus it was that his individual spirit acquired an outer boundary. On the other side of it there is no longer anything to be found – no pictures with which it would be possible to enter into any kind of connection. This condition recalls, in fact, that of the unitary God be- fore the primal revelation, while being, admittedly, diametrically op- posed to it at the same time.

A kind of shadow of picture quality does, indeed, come to expression in abstract thinking, but without actually belonging to it. It belongs to the thought-being who lives in the union of percept and thinking. Eduard von Hartmann was right to say that in every act of thinking something is preserved of the sensory experiences of colour, sound etc. We will be discussing this question in more detail later, and will examine it from the aspect of the esotericism of the thought-process. For the present, we would refer to a number of statements of Rudolf Steiner, where he says that in response to every sense-perception a counter- movement of ideas takes place from within the inner sphere of the human being. When we are given over to the senses – and thus also to the pictures – we are living in the etheric world. The movement from this world passes into our ether-body, then into our physical body, where it undergoes a “blockage” as it meets with the counter-thrust of the ideas. Thus the living, etheric movement – this comes to expression in the circulation of the blood – is “paralyzed”, so to speak, and deadened by the physical organism of the nerves. The consequence of this is that we see physically: we see physical instead of spiritual pictures (cf. GA 198, 10.7.1920; GA 206, 12.8.1921).

The process we have described also brings the astral body into activity (as was the case in the aeon of the Old Moon): the processes of breathing, of taking in nourishment and, finally, of perception are accompanied in our astral body by desires, sympathies and antipathies; this is also where instincts arise; impulses to action emerge. All this leads in gradual stages to a permeation of a part of the astral body with human consciousness, and out of this the sentient soul is formed. All the processes active in it take on a picture character and form us from within. The true cause underlying them – the influence coming from without – is the coarse sense-reality to which the human being should not surrender himself completely. It works in him with a deadening effect, arousing in us antipathy, which comes to expression in the form of reflection and abstract thinking.

If the breathing-process is not encumbered with coarse desires, more oxygen is retained in the blood; the threat to the human body diminishes and sympathy arises in the astral body. The physical body then offers less resistance to the stream of perceptions, and picture-thinking begins to gain the upper hand in us. The human being now finds in his heart the capacity to enliven the abstractions with experiences. It is not a sensory form of vision that is meant here, but a process of spiritual enlivening, where in the initial stages spiritual symbols can be of help to the seeker for knowledge. It is possible with their help to rise from the sentient soul to the higher soul-regions.

The life of the senses in the human being has a dual nature: the lower, which gives rise to abstractions (those of materialism, of consumerism etc.); and the higher, which has been purified. Both the former and the latter continually form pictures in the astral body which separate off from our experiences and remain within the soul, whereby they build up its organs. Hence, the soul is the body of the pictures, in which our ‘I’ is active. On the other – spiritual – side, the exalted hierarchy of the Spirits of Form, who are actually the creators of the earthly aeon, also give shape to their intentions – today as they did in the past – in the form of pictures. Their revelation is the hierarchy of the Angels, thanks to whom the pictures of the Elohim are carried into our astral body. This came to expression with great force and spirituality in the Christian icon paintings, through which the self-proclamation takes place, of the imaginative cosmos of the God who has descended to earth.

The human being of today who cultivates pictorial thinking, begins to participate in the creation of the future. His task is to rise from the pictures of outer perception and of the lower life of the senses, to the higher picture-thinking of imagination. Where half the journey has been completed, ideal beholding arises.

5. The Pure Actuality of Thinking

Let us summarize the conclusions we have come to in the course of this chapter. The primordial world-Being, the pictureless beginning of the world, the “immovable Mover”, acquires in the process of creation a form, a picture, and reveals Himself as a multiplicity of pictures: creative thought-beings. Their deeds of sacrifice in the world create an object: the material world – the picture of the creative hierarchical subjects.

Within the material

world the Divine primordial Being, the Absolute,

inwardizes itself, and finally assumes

the character of conceptual systems

(world-views) in the human being. As a

consequence of this inwardization there arose a

relation between the unbounded World-‘I’, and

the point-like ego-centre in man, the centre of

his lower ‘I’, which is the fruit of

sense-perception and thoughts (Fig.70).

Within the sense-perceptible universe a further inwardization takes place as the being of man unfolds. This time, so we could say, there is a repetition of the great lemniscate of the world expressing the relation Nature – Man. The sensory universe inwardizes itself in the soul-spiritual world of the human being. In this way it cancels itself, because the inner being of man can objectify itself directly in the “outer sphere” of the spiritual universe. Thus it would be true to say that from now on the spiritualization of nature must also take place. But the lower, lesser ‘I’ is not able to fulfill this task. It must itself be cancelled (aufgehoben) to make way for the higher ‘I’.

An immature person who cancels his lesser ‘I’ loses himself, and it is therefore his task to strengthen and metamorphose it. Strengthening lies in evolving further, whereby the human being follows the same path as that through which he finally became a personality. This is precisely the path of development suggested by the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. The recommendation is made that, to begin with, one should devote oneself to a fundamental grasping in cognition of the sense-world, which is condensed spirit, given to us in sense-perception. The task is to unite with the world of percepts the spirit – pure, but lacking in substance – of concepts, while at the same time it is necessary to instill into this spirit one’s knowledge of the spiritual foundation of the world. We thus create for the Divine primal Ground of the world – which, in its working, had been mediated by the hierarchy of pictures which are at the same time beings, and again assumed within us a pictureless, non-substantial character – the possibility of reuniting with its inwardized part: namely, with the sensory pictures of nature. Nature contains within it the Divine substance; this is given to us in our perceptions. And if we unite with it no more than a shadow of the true world-Spirit, we restore the original unity of the world and thereby sanctify the world of Being.

The science of nature must become ethical, and will unavoidably take this direction at some point in the future; the research scientist of great learning will experience his laboratory table as something like an altar – or as an altar. Goetheanism does this already, by bringing the supersensible into the inner representations of nature. Then the human being, as he advances towards the supersensible, takes nature with him, and does so increasingly, the more he overcomes sense-perceptions. Thinking then becomes pure. Following Aristotle, we can call it “pure actuality”. As opposed to the unconscious, it can be given form by the human being, thanks to the identification of thinking with pure will, which is directed exclusively towards itself. Just as one can reflect back towards oneself, so it is possible to direct the will towards itself. In this will is revealed, not the world-Spirit, but the world-Will, the will of the Father, by whom was created all that is.

Already at the stage of abstract thinking one must try to engage the will. In the case of a good dialectician, the thinking frees itself from the object and draws living movement from the self-perception of its own dynamic, whereby the need for the physical-material body as a support for self-consciousness is gradually overcome. The value of abstract pure thinking lies in the fact that we bring it about actively. But dialectics can be upheld ideally as the autonomous movement of the world-Idea. For this reason, Hegel was a universalist in the realm of logic.

Abstract thinking is bound up with the astral body. In the first stages of abstract thinking, certain fine threads of our spiritual sense-organ extend themselves outwards. When we think about pure Being we have, in feeling, a very fine and subtle experience of the life of the world. Within our sense, the “overtones” of different levels of being merge together momentarily into a general “tone”. We are breathing out astrally. When this has been overcome, we breathe in astrally, and then the pure will comes into action. The process which unfolds in this way spiritually goes hand in hand with a process in the body. We breathe out carbon dioxide – the more so, the more abstractly we think – and we breathe in oxygen, which renews the metabolic processes in which the unconscious will is active. The act of pure thinking stands in connection with the holding of the breath when one has breathed out to the greatest possible extent.

The pure actuality of thinking allows us to retain consciousness when it has been emptied of all content. In its highest expression this is a state of intuitive consciousness in which “All in All” is experienced. This is the state of Nirvana. But in the initial stages the lesser ‘I’ is strengthened through the – merely sporadic – experience of pure thinking. This allows us to begin the process of the observation of thinking, which passes over gradually into an intuitive process when we enter into the stage of pure beholding. “In the observation of thinking,” says Rudolf Steiner, “the world-process becomes transparent to the human being. He has no need to seek for an idea of this process, as this process is the idea itself” (GA 6). And it is also the higher self of the human being.

When the human being transforms his own thinking into experience, percept, and when he continues to work with it as an object of thought, he creates a higher nature within himself. His thinking begins to rest upon the support of the etheric brain; but it is in the etheric world that true picture thinking lives. Through pure thinking we ascend to the individualized pictures, to the pictures of essential being. But where are these first experienced by our ‘I’, which arrives at a state of identification with them? It experiences them as the outer aspect of the objects given to us in perception as the secondary qualities of things. There takes place in thinking, when we make it into an object of observation, the transition from the primary to the secondary qualities; which goes hand in hand with a profound and far-reaching metamorphosis of the entire human being. In pure thinking, our ‘I’ also becomes picture (cf. A.7, 1929).