Rudolf Steiners "Philosophy of Freedom" as the Foundation of Logic of Beholding Thinking, Religion of the Thinking Will, Organon of the New Cultural Epoch

Volume 2

Part V. The Religious-Ethical Character of the Thought-Metamorphoses

Chapter 3 – Thinking as a Means of gaining Knowledge of the World

Let us briefly recapitulate the way in which the Divine Tri-unity reveals itself as the plan and the fundamental law of our evolutionary cycle. The process of becoming arises from the eternal, and both of these are contained within the principle of universal all-unity. This can be described as follows in the language of philosophy: the Father-principle of All-unity is the universal consciousness in itself and for itself; in the hypostasis of the Son the All-unity is the all-encompassing being (life) of the universal consciousness in itself and for itself; in the hypostasis of the Holy Spirit the All-unity is the existence of the universal consciousness in itself and for itself. At the beginning we have a self-conditioned conscious All-consciousness, then movement, the being (life) of this consciousness, and finally its form (the being of the form). The universe also is structured in accordance with these three categories. The law of its form is the underlying idea of the world. Thus Goethe was of the opinion that the idea is one and eternal, and that the entire multiplicity of the ideas which are manifested in the phenomenal world can be traced back to it as their primal form. The primal idea is on a higher plane than the process of becoming and for this reason it is one and the same at the beginning and at the end of the world. But at the end it is separated from the beginning by the process of becoming. Becoming unites the idea of the world as form, as that which is conditioned, with the All-unity that is unconditioned. This is how freedom comes into being.

The idea in manifestation becomes the multiplicity of the forms of the world (cosmic, botanical, historical, spiritual etc. forms). In correspondence with the classification of the forms we can carry out the classification of the ideas of existence. The metamorphoses of the forms are, moreover, identical with those of the ideas and vice-versa. For this reason, our analogy between the seven-membered metamorphosis of the plant and that of the cycle of thinking which we arrived at in the course of our previous investigations, is quite legitimate. The spiritual affinity between Hegel and Goethe stems from the fact that one of them studied the pure idea in its manifestation, and the other the manifestation of the idea in things. Their movements converged. Thus, to express it in Rudolf Steiner’s words, “Goethe stands towards us as

the spiritual substance and Hegel as the spiritual form” (GA 113, 28.8.1909). In their time they had no connecting link which could join their world-views together. This lack was a result of the preceding evolutionary process of the world; but it is thanks to the same process that the link finally came into being, namely Rudolf Steiner’s theory of knowledge, through which the existence was objectively demonstrated of the living idea that is given in the world of perceptions. Its becoming in the human being is the process whereby he comes to freedom. This is also what the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ is about.

The world tri-unity expressed itself on the level of human self- conscious being in the tri-unity of experience, of theory (world-view) and their connecting link: the thinking ‘I’, which also has the capacity of introspection, of self-observation. This phenomenon – the latest to appear in world-evolution – can only be understood if knowledge is sought of the principles of the becoming of the world, and this we are striving to do with the help of spiritual science.

On the macro-level the idea of the world, or the existence of the universal consciousness in itself and for itself, is identical with the seven aeons of our evolutionary cycle. Their unity can be described as potential. In the second Logos world-unity bears a dynamic character, in the first Logos it is substantial. God is one, not only in and for Himself, but also in each of His hypostases. One can experience them as three absolute qualities, each one of which contains the two others within itself. In the realm of manifestation their relationships and the ordering of their activity change, and this comes to expression in the structural laws of the universe.

The Divine Tri-unity emerges from the world of the Great Pralaya as the plan of the new universe. This consists in the process whereby the primal impulse proceeding from the All-consciousness of the Father, reflected and endowed with life in the Son, and then attaining form in the Holy Spirit, returns to the Father (is reflected back), but in such a way that the unitary Divine consciousness engendered the multiplicity of existing forms of consciousness, filled them with itself, and, after it had transformed them, brought them together into a higher unity. It is not necessary to inquire after the reasons for the emergence of such a plan. Divine consciousness had no need to fill anything whatever with itself. “It has everything within itself,” says Rudolf Steiner. “But the Divine consciousness is not egoistic. It bestows upon an infinite number of beings the same content that it has itself” (GA 155, 24.5.1914). Of paramount importance for it are love and freedom. But through filling beings with itself, the Divine consciousness enters into a relationship with them – and now it has need of them and endeavours to raise them onto its level. This is why love and freedom form the foundation of the structural laws of the universe. The laws of natural development are derivative from them. The forces of the material world – magnetism, gravitation etc. – working in the human body are placed between the moral principles of good and evil. The world is governed by an ethical principle. Everything proceeds from this and returns to it again.

The transition of the Divine plan into the stage of realization is mediated by the beings of the First Hierarchy, above all by the Seraphim. The name itself, says Rudolf Steiner, means, if it is rightly understood in the spirit of ancient Hebrew esotericism, that they “have the task of receiving the highest ideas, the goals of a world-system, from the Trinity” (GA 110, 14.4.1909). The Seraphim are the highest beings of universal love. One level below them are the Cherubim, who are the beings of the highest wisdom which, in this lofty sphere, forms a unity with universal love. It is their task to ‘elaborate’ the goals which they have received from the Trinity. But the immediate realization in practice of the Divine plans is the task of the Thrones, the spirits of will. They possess the power to translate into an initial reality that which has been thought through by the Cherubim (ibid.). They accomplish this through the act of offering up their own substance in sacrifice ‘on the altar of creation’, out of a higher love for the deed.

Through the working of the beings of the First Hierarchy the Divine Trinity enters gradually into an immanent relation to the new configuration of the universe. This transition occurs through the hypostasis of the Holy Spirit, which stands closest to the world of the Divine Hierarchies. It is the countenance of this hypostasis which the Seraphim behold. It reveals to them the idea of the world, the plan of creation of the new evolutionary cycle. This idea (plan), when it becomes a possession of the Hierarchies, is then ‘thought through’ by the Hierarchy of the Cherubim, who thereby already endow it with life in the world of the Hierarchies; and in this the working of the hypostasis of the Son comes to expression. Finally, the Thrones, or spirits of will, mediating the impulse of the Father, sacrifice their own will-substance. Rudolf Steiner describes this process as follows: “First, the Holy Spirit worked down into the astral material. Then the Spirit, having united itself with the astral material, worked down into the etheric material, that is the Son; and then comes the Father who governs physical density. Thus the macrocosm is built up in three stages: Spirit, Son, Father...” (GA 93, 5.6.1905). The principle of creation thus described has a universal character and has already worked in the course of several aeons. “And the human being,” Rudolf Steiner adds, “as he works his way up again [through his own forces – G.A.B.], goes from the Spirit by way of the Son to the Father” (ibid.). He ‘goes’ in the Manvantara that is revealed to the senses, while the interrelation described above, between the Trinity and the Hierarchies takes place in the upper, spiritual conditions of the form of the Manvantara. And these conditions are preceded by the primal revelation of the Father towards the Son, and of the Son towards the Holy Spirit, this remaining unchanged in the world of the Great Pralaya for all seven aeons.

All of the three stages

we have indicated in the evolution of the world

stand in a close relationship to one another.

Once we have grasped this we will also

understand the capacity of the human spirit to

stand upon its own foundations. The

seven-membered lemniscate of thinking has as its

‘ur’-phenomenon the lemniscate of the working of

the world-principle. However, the first

beginning of its becoming is rooted in the world

of the Great Pralaya. If we try to draw up a

picture of these interrelationships, this will

illumine for us the extremely crucial

peculiarities of the path of the human being to

God, which passes by way of the sphere of

thinking.

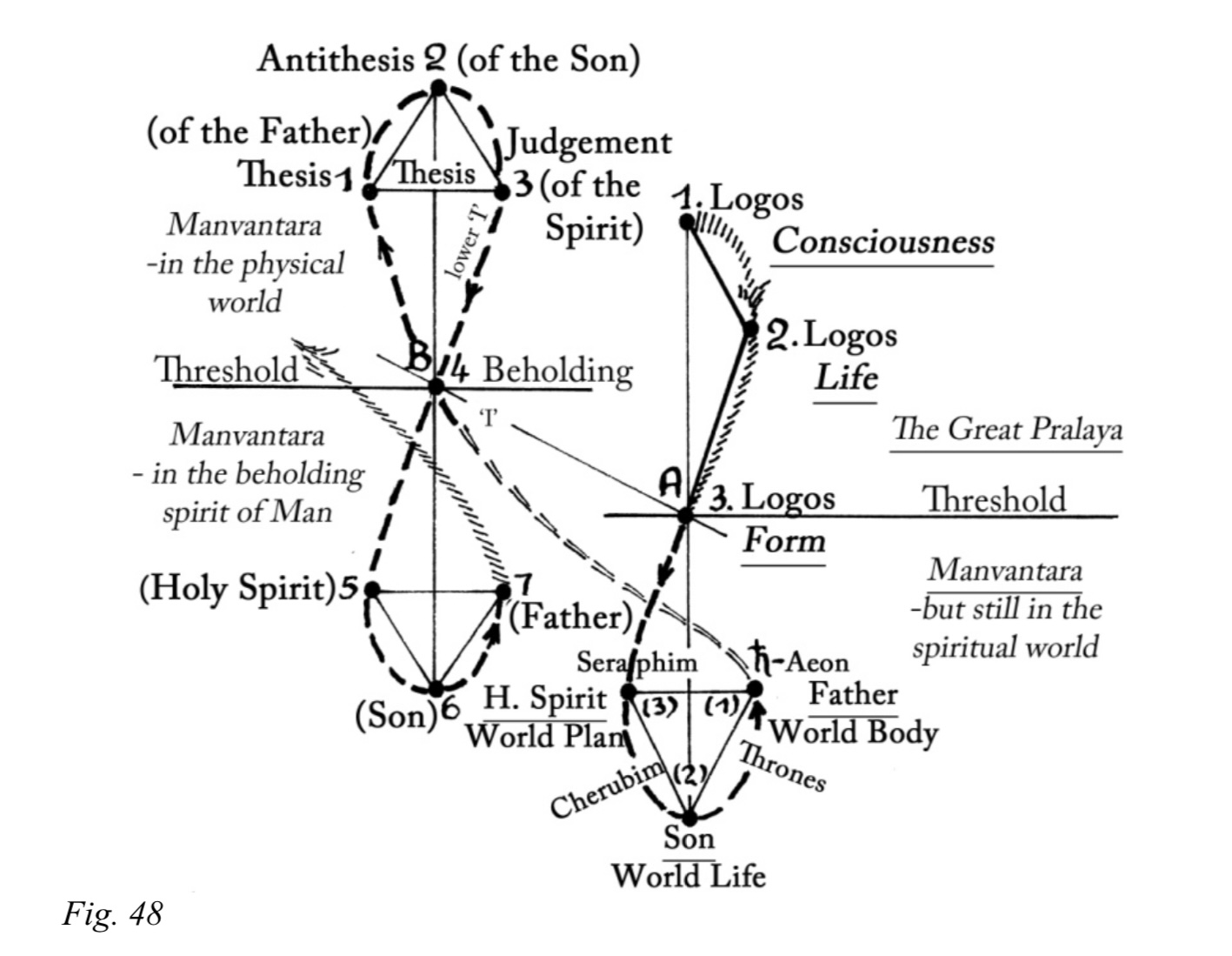

As we see from the new diagram, that which we described earlier in connection with Fig.9a and b represents the first beginning of the becoming of the lemniscate of world-development. At this beginning the third Logos brought about the crossing of the threshold separating the primal revelation from the process of creation. And he, the third Logos, the Holy Spirit, laid the foundation-stone of this creation by revealing to it its plan. Between these two manifestations of the Holy Spirit the Seraphim provide the basis for a relationship and act as a mediating element. Then the primal revelation unfolded once more, but in the re- verse order. Rudolf Steiner also speaks of this in the words we have quoted. The outcome of this was that the substantial-material beginning of the world’s becoming was established – in the Father on Old Saturn.

The further development of the Manvantara began to shift ever further into the world of otherness-of-being. On the threshold to it, where in the first instance the Holy Spirit stood (Fig.48, point A), there appear in sequence, from aeon to aeon, the beings of the Hierarchy (point B). At the end of this process there comes into being dialectically-thinking man. Behind the triads of his thinking stands, in a quite shadowy way, the Divine Tri-Unity. In dialectic the human being goes from the Father to the Spirit, to the individual judgments through which the lower ‘I’ lives. When it has grown sufficiently strong, it raises itself up and crosses, in beholding (element 4), the threshold of consciousness and metamorphoses into the higher ‘I’, which lives through the power of judgment in beholding. Thus begins the path of the human being from the Spirit, through the Son to the Father, who imbues the striving of all revelations of the world-idea, including those of an abstract nature, with the impulse towards All-unity. The human being must move many times on the lemniscate of morphological thinking before his sense of thought and his power of judgment in beholding attain their highest development. But when they become a possession of his individual spirit, what direction will he take then? He will move into the lower part of the world-lemniscate: to the Manas of the Holy Spirit, then to the Buddhi of the Son and to the Atma of the Father. After this he will stand as an individual, self-conscious spirit on the threshold of the Great Pralaya.*

* Fig.48 enables us to

understand that in the dialectical part of the

lemniscate we are dwelling, albeit

unconsciously, within the sphere of the first

tri-une revelation.

_______

Such are the

relationships between the phenomenon of the

thinking ‘I’ and its cosmic ‘ur’-phenomenon. The

difference between them is simply colossal. In

order that they may be able to unite again,

world- evolution unfolds as the seven-membered

system of the aeons (Fig.49). The Divine Trinity

enters into an immanent relation to this

evolution, but in such a way that, here too, the

subsistence, the self-conditioned existence of

universal consciousness, remains an absolute

unity, to begin with only in the spiritual

phenomenon which is borne by the Hierarchies.

But after this, the

Manvantara begins to unfold in time, and then in

space. In them is revealed the ‘other’ of

universal consciousness and of the entire Divine

Tri-unity. Rudolf Steiner says that the higher

relationships which take place within the

Trinity take on an opposite character in their

transition into the Manvantara which is

undergoing materialization (its higher aspect

‘tips over’, as it were, or finds its mirror-

reflection in the lower). Thus we have in the

first Logos a higher spiritual world, but its

mirror-reflection in the third Logos represents

the “reverse activity”, which is “the most

extreme spiritual darkness” (GA 89, 10.11.1904).

We find it in the realm of the minerals and also

in reflective thinking. The life in the first

Logos, which sacrifices itself, is at the same

time love. In the second Logos it is life that

has been ‘received’. In the third Logos, which

is of course active in the Manvantara, it

becomes ‘absolute desire’, ‘yearning’ for the

first Logos, the striving to return to its womb.

Finally, the third Logos becomes a single

‘reflection’ of the first Logos (ibid.). This is

the nature of its working in the human being. In

its form of thinking consciousness the human

being leads an existence that is spiritual, but

devoid of substance. There lives in him the

‘yearning’ for a consciousness that is filled

with life and light. It is by virtue of this

yearning that the movement takes place of the

dialectical negation, the setting aside

(Aufhebung) of the idea in its reflected form.

The subsistence of the universal consciousness

was changed, in the thinking form of human

consciousness, into darkness, but the descent

into spiritual darkness was (immediately after

the expulsion from Paradise) accompanied by the

birth of absolute desire in the astral body. It

gave rise, in otherness-of-being, to the

darkness of the lower desires, but the higher,

primal desire, as a yearning for the higher and

individual spirit, led the human being onto the

path of the development of the threefold soul.

After the Mystery of Golgotha the higher,

spiritual light shines directly into the

darkness of the soul- spiritual existence of the

human being, who therefore has no alternative

but to make an effort to receive it into

himself.

Everything that falls out of the light of universal all-consciousness sinks into the darkness of outer existence. It is in a condition of spiritual darkness that, in the aeon of Old Saturn, the sacrifice of the Thrones was transformed into external warmth. Absolute desire manifests in every moment of becoming as a transforming, renewing and ennobling force. In the human being it gives rise to the driving force of action. But desire has a reverse side, a counter-pole, where the power of the wish causes darkness to densify, thus leading also to a coarse materialization of the Earth. In the human being this extends into the processes of perception and thinking, when the living substance of the nerves is mineralized. This is the theme of the ninth chapter of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’, which we will be speaking about in due course – the theme of the ambivalence of the motives and driving forces to action. The basis for the life of soul and spirit in man lies in the triune body. Standing over against its darkness (the unconscious) is the formative power of the world of the triune spirit: Manas – Buddhi – Atma. The working of the second Logos in this tri-unity comes to expression as the unity of consciousness (light) and life. Christ raises, ennobles desire in the human being through the fact that he works in a unity with the Father, who offers up His life in the Son. This is why we say: God is love. In this unity with the Father, Christ can say: “I am come a light into the world ...” (John 12, 46), and: “I am the bread of life”; “I am the bread which came down from heaven”; “I am the living bread” (John 6; 35, 41, 51). The light of the Christ-’I’ shines into the ‘darkness’ of the small ‘I’ of the human being, and after the Mystery of Golgotha, where God sacrificed Himself, it can imbue the human being with life if he does as Christ did, and sacrifices this small ‘I’. After Golgotha the principle of universal love united with the Earth. But the human being achieves reunion with this principle through developing love for the object of cognition, whereby beholding begins.

All that happens to the human being in the way described has world-encompassing significance and is rooted in world evolution. Seven times the earthly aeon passes through seven form-conditions and gives rise to seven life-conditions. Out of the 7 x 7 form-conditions there emerges in otherness-of-being a certain form of consciousness – waking, object-oriented consciousness, which has its support in the experience of sense-perception and conceptual thinking. Its inner structure is threefold. Its first element is the inheritance from the sphere of the Father: picture-thinking; the second is the actual orientedness towards the object – analytical and pure thinking in concepts; the third element begins with the development of the power of judgment in beholding. The second element of consciousness must become Christ-filled in the human being, but in the present stage of development it is just in this element that the deepest fall of man from God takes place. The power of judgment in beholding remains, for the present, foreign to the human being. Its archetype is to be found in the Whitsun Festival which, it must be admitted, is also alien and incomprehensible.

The temporary fall of man from God is due to the necessity that the human being should pass from natural, objective evolution to his own, ‘I’-evolution. In this too, we find a manifestation of the world-idea: on the level of the becoming of the human ‘I’-consciousness. For the sake of the latter, a special law of development is instilled by the world-idea into the entire fourth round – into its seven form-conditions, in the fourth of which we are now. Here the greatest materialization of the spirit takes place, the ‘groaning and travailing’ of the creation for the spirit reaches its climax, but at the same time “the light shineth in darkness” (John 1, 5). This is the living light of All-consciousness, which must be ‘comprehended’ by the darkness of human abstractions. And this it has the ability to do, because it shares with it the same primal source. Here we have to do with the poles of a single, unitary whole. The Holy Spirit in this mighty striving out of the future towards the Father-God has ‘perforated’, so to speak, all spheres of otherness-of- being, has rejected all forms of what has become, has eliminated the principle of life itself in man, has called forth in him the death of matter which is not the result of a natural process, thereby liberating the human being from it, but ... as a shadow of the spirit! For the Holy Spirit has accomplished this within the human being without the involvement of the Son. “Thinking,” says Rudolf Steiner, “is the latest element in the sequence of processes which build up nature” (GA 2). At the same time, it constitutes an exception within this sequence. In its essential nature thinking is the activity of the Holy Spirit in man; but in abstract thinking He is not present. This is Luciferized. For the Holy Spirit always works with the substance of the Father, endowing it with form, but now a form arises in which the Father substance is coming to an end, is dying. Thus the problem arises: how can one endow such a form with life? In one of his lectures held in 1920 Rudolf Steiner describes the process in the course of which the thinking that has lost its substance can regain it. He explains that the whole form (Gestalt) of the human being, right down to the physical body, is woven by universal forces which come from the twelve regions of the Zodiac. When we think, they enter into the sphere of the interaction between nerve processes and blood circulation, breathing and metabolism. In the distant past, before the Mystery of Golgotha, thinking, which was accompanied by the metabolism in the head, incarnated in us as it were through coming from outside and uniting with the material substance of the body. In other words, the wisdom of ancient times (which had a perceptual character) was a continuation in the human being of the universal process of the densification of the spirit to the material condition.

But from as early as the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. there has taken place a metamorphosis of the above-mentioned processes, as a result of which the thought-pictures are growing empty. The head activity is simply beginning to accumulate pictures and cast off the material element. This is how the transition to pure conceptual thinking took place. In it “everything of a material nature that was involved in the inner life of man” falls back into the organism, “and only the pictures remain.... Our soul lives in pictures. And these pictures are what remain of all that existed earlier. It is not the material, but the pictures which remain” (GA 201, 16.5.1920). The matter that, in this form of thinking, is cast off like debris, disappears out of three-dimensional space. Its atoms, Rudolf Steiner says in another connection, pass over into the realm of Ahriman, and he creates out of them a kind of anti-Jupiter, an aeon of empty pictures out of which in the aeon of Jupiter its companion planet will be condensed, as a terrible relic which preserves within itself the realm of the minerals. Thus the human being who persists in the abstract weaving of thoughts is unwittingly a creator of world-evil.

* * *

It is necessary at this point to digress somewhat from our theme and speak about the spiritual-scientific idea of the atom. In this question, too, one needs to go back a long way. Our (fourth) etheric-physical globe (the form-condition) is composed of four kinds of ether: warmth, light, chemical (tone) and life ether. Through their activity the densification occurred of the material substance of the planetary system, which is represented on the Earth by four elements: warmth, air, water and earth (at a later stage we will be looking at these more closely). The densification of the elements to the condition of coarse substance was predetermined from the beginning of the evolutionary cycle and was contained within the world-plan received by the Seraphim from the Divine Tri-unity. One can find an individualized relationship to this plan of world-evolution. This was at all times known to the great Initiates – semi-divine and human beings who were considerably in advance of the general development of humanity. In harmony with this knowledge they instituted, for example, the rituals of initiation in the Mysteries, where the human being, for the first time, began gradually to take hold of the individual ‘I’. In antiquity he achieved this by sinking into a lethargic condition in which the astral and etheric bodies were separated from the physical. And at that time the pupil imprinted everything of a lofty, individual nature that he was able to imprint into his astral body before initiation (after he had purified it of animal tendencies) into the etheric body, i.e. the life-body, imbued it with the Holy Spirit and ascended – as we said above – on a ‘reverse’ path from the Spirit by way of the Son to the Father. It was not possible for the wisdom of Manas – the ‘Word’, as it was called in those days – to enter the etheric body in any other way. Through undergoing the initiation process, the pupil was able to prevent his etheric body from being dissolved in the world-ether, and to ascend with it – in an individualized form – into the upper Devachan (see GA 93, 5.6.1905).

The ether-body of the Initiate that had been imbued with the Word had a special effect upon the physical body and implanted into it the plan of the coming aeon of Jupiter, where the physical will not densify to the mineral condition. Rudolf Steiner speaks of the highest Initiates of the Earth who, on their level, fulfill continually the work of the First Hierarchy, which perceives and works through the plan of the world, and “when our Earth has reached the end of its planetary development, then the Masters of Wisdom and the Harmony of Sentiments (this is the name of these Initiates in esotericism) will have completed the plan which they have been working upon for Jupiter. And now, at the end of such a planetary development something quite extraordinary occurs. Through a certain process this plan is at the same time reduced in size and multiplied, both to an infinite degree. So that there is an infinite number of copies of the entire Jupiter plan, but in miniature. So it was also on the Moon: the plan of Earth-development was there, infinitely reduced in size and infinitely multiplied.”

Rudolf Steiner continues as follows: “And do you know what this is, this miniaturized plan which has been elaborated in spiritual realms? These are the real atoms which form the basis of the Earth. And the atoms which will form the basis of Jupiter, will again be the plan – reduced to the smallest dimensions – which is now in process of development in the White Lodge (of humanity). Only if one knows this plan can one also know what an atom is”* (GA 93, 21.10.1905).

* Some scientific

phantasies are materialistic interpretations of

highly spiritual truths. For example, the

astronomical conception of the origin of the

universe as the result of an explosion of the

primeval atoms which became concentrated to an

infinite degree; and also the idea of the

“permanent” atom, which contains within it all

information about the living human being and

leads it over into a new earthly existence.

______

Such is the

working of Ahriman in the thinking consciousness

of man, where he strives to win control over the

atoms of dematerializing matter in opposition to

the work of the great Initiates. This is the

opposition between universal Good and universal

Evil.

The human being stands at its centre, at the meeting-point of Good and Evil, and has the task of helping to transform Evil into Good. Traditionally, he does this in the religious cult where the mystery is enacted of the transubstantiation of the earthly elements. (This mystery, too, cannot be understood if one does not acquire knowledge of the nature of the atom according to spiritual science.) But the cult alone is insufficient, since beyond its limits the human being engages in an intellectual, thinking activity. He must learn to worship God “in spirit and in truth”. The first step in this learning process is the development of morphological thinking, which is based on ideal perception. Thanks to it, the human being no longer needs the support of matter, in whose atoms the plan of the old universe, our own aeon, is exhausted.

On the other hand, Ahriman is striving with all his might to hold the human being imprisoned in the intellectual element and within the sphere of purely materialist conceptions. In these strivings he appeals to the past, to the world that ‘has become’, where the subsistence of the Father principle has become, finally, the dialectical subsistence of the consciousness that thinks in concepts. One should not reject this element that has come into being, one can only transform it, if one has first understood that thinking is able to work upon matter directly, but also that manipulations carried out on matter influence thinking. Conceptions of the quantum nature of thinking; of torsionary fields possessing only one property, namely the transmission of information; of neutrinos – photons which have neither charge nor mass nor magnetic properties, but nevertheless have infinite duration – create together with the thought-activity of man the Ahrimanic future of the Jupiter aeon, and within the Earthly aeon they lead human consciousness into a symbiosis with the electromagnetic fields.

In their true meaning and significance all the latest discoveries of physics serve as confirmation of the fact that there is nothing spiritual which does not come to manifestation in some way or other within the physical-etheric (in the phenomenon of the living) or the physical-mineral world. One must not arrive at thinking by starting from matter, as it is spiritual even in its abstract form; the materialization of the world was merely an – albeit inevitable – consequence of its coming into being.

* * *

In the lecture already quoted, of 16th May 1920 (GA 201), Rudolf Steiner speaks of Parzival as a soul who strove to instill “substantiality, inwardness, essential being” into the empty “picture-existence” of the human consciousness which can crystallize out when everything of a material nature has been ‘filtered off’ from pictorial thinking, from the pictorial, mythological conceptions of ancient times. Much is required of him for the attainment of this goal: He must stand in the centre where the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table experienced the workings of the twelve Zodiacal forces, within his own individual ‘I’, and unfold from this an activity of his own which streams in a direction counter to those cosmic forces. He attains this capacity through finding a relation to the Christ Mystery. Since that time every human individual is confronted by the problem which was solved by Parzival. Through carrying out a polar inversion of the spiritual (knightly) orientation of Arthur’s Round Table, Parzival anticipated on a Mystery level the great metamorphosis, as a result of which the work on the plan of world-development which had previously gone on in the hidden sanctuaries of the Mysteries pressed outward to the surface of cultural-historical life. Goethe and Hegel, already in the new culture-epoch, enter into that relation in which Parzival had stood towards Arthur’s circle. Hegel is now the bearer of the spiritual form. Goethe comes forward in the role of the new Parzival as the bearer of the spiritual substance. In contrast to Hegel, he wishes only to have to do with substantial, individual thinking which has the character of essential being. To this extent he is both a traditionalist and an innovator, as we are not dealing here with the old substance, which filled the thought-pictures in accordance with the (in the wider sense) natural laws which excluded an individual relation to the pan-Intelligence. He seeks for ways of filling the empty forms of pure thinking with new substance – the ether-substance of the risen Christ. There arises within the cultural process a mirror-reflection of what is referred to at the beginning of the St. John’s Gospel. The individualizing process from the trans-temporal world of essential being enters into the form prepared for it by cultural activity.

Hegel could have said in the words of John the Baptist: “He that cometh after me is preferred before me: For he was before me”. Finally, at the transition from the 19th to the 20th century, a cultural-historical polarization takes place of the old Mystery relationship: In the role of Parzival, Rudolf Steiner comes forward with the idea of freedom, and the entire form of the old civilization in a state of decline opposes him. As a means of rescuing civilization he points (after he has created the appropriate methodology for this) to the necessity to resurrect subjectively in thinking, thereby paving the way for that great resurrection which Christ has shown to the world.

In thinking, the possibility is opened up to the human being for the first time, of a deed that is pregnant with destiny and, in the fullest sense of the word, his own: to set himself aside as a thinking subject and become conscious as a subject that is capable of ideal perception. This means that, of reflection, only the will-element must remain, which enables one to behold the dialectical movement of ideas. A purely willed state of consciousness is possible only if it has been completely freed of all sensuality, of all – figuratively speaking – ‘hirsuteness’ of the brain, i.e. from the proclivity to the animal life of the passions and desires which manipulate the thinking. When thinking attains pure subsistence,* favourable opportunities are created for the will to set aside its reflective character and fill the pure form of the individual spirit with the ether substance of the pan-Intelligence.

* Subsistence in the

philosophical sense is what exists through

itself, and is founded upon itself.

______

If we have grasped this, we arrive at the following insight: “Anyone who grants to thinking a capacity of perception that extends beyond the realm of the senses must, of necessity, also concede to it objects that lie beyond the sphere of mere sense-perceptible reality. But the objects of thinking are the ideas. When thinking takes hold of the idea, it merges into one with the primal ground of world-existence; that which works outside him enters into the spirit of man which becomes one with objective reality in its highest potency. The act of becoming aware of the idea in reality is the true communion of man” (GA 1, p.125). When we ‘behold’ the movement of pure thinking, we can experience its identity with the will. And to do this is our task and ours alone, as it is revealed to our beholding spirit, the ‘I’, even beyond the realm of the sense- world, that “the living idea, the idea as percept ... is only given to human self-observation” (GA 6, p.206). In such a process of self-observation the apparatus of thinking becomes the organ of ideal perception. And because everything occurs on a super-individual basis, the ‘I’ reveals a creative character; it fills thinking – following already the laws of the future world – with ether-substance, and calls into being those laws according to which the resurrection of matter takes place: Its atoms are spiritualized by means of the thought-willed creative activity of the subject. The individual human Manas comes into effect, through which the Holy Spirit proclaims His message of blessing. He proclaims the Christ in the individual ‘I’ of the human being. Christ therefore says: “But the hour cometh, and now is, when the true worshippers shall worship the Father in spirit and in truth; for the Father seeketh such to worship him” (John 4, 23). Their ‘worship’ consists in the real salvation of the substance of the Father from Ahriman, from the descent beyond that limit where the primal plan of world creation is distorted.

If we approach our work with thinking out of such an understanding and with such an inner attitude, that of which Heinrich Leiste rightly speaks does, indeed, begin to happen: “A friend of Anthroposophy, who has studied it earnestly for a longer period of time suddenly awakens to the insight which moves him deeply, that he stands towards Anthroposophy in a Mystery situation. This is the moment when he enters the outer precincts of esotericism, of the new Mysteries. He knows now that his inner existence must be completely rooted in the spiritual ground of the ‘Philosophy of Spiritual Activity’. And he clearly senses that his nature as a free being requires of him that, even in his work with Anthroposophy, he should be free, that is to say creative. And the fact that Anthroposophy was brought down by its founder to the level of a ‘philosophy concerning the human being’ takes on significance with regard to method. Thus, as its pupil, he had initially to do with something that is highly spiritual, but still no more than a philosophy. He must try, with the help of this philosophy and through the light it sheds, to come ever closer to Anthroposophy as a being, but creatively. And in the course of this soul-journey he fashions within his heart a developing philosophy of his own: Anthroposophical philosophy.... The method whereby Anthroposophical philosophy is attained is the ‘Philosophy of Spiritual Activity’.”131

Anthroposophical philosophy is a doctrine of science (Wissen- schaftslehre) which unites within itself gnoseology with the science of initiation on the basis of a new teaching regarding the soul – psychosophy. This is in the final analysis the philosophy of the Holy Spirit, or the Christianity of the Holy Spirit, of which Christ speaks as follows: “But when the Comforter is come, whom I will send unto you from the Father, even the Spirit of truth, which proceedeth from the Father, he shall testify of me” (John 15,24). He proceeds from the Father out of the trans-temporal heights, where all seven aeons exist simultaneously, where the Saturn of the past and the Vulcan of the future form a single whole (see Fig.40). In evolution He gives to the Father-impulse the forms of which the last is the abstract logical form of thinking. This has to be overcome. Christ therefore continues by saying: “Nevertheless I tell you the truth; it is expedient for you that I go away (a reference to Resurrection and Ascension – G.A.B.). For if I go not away, the Comforter will not come unto you; but if I depart, I will send him unto you” (John 16, 7). In the future He will ‘not come’ on the general path of evolution to the human being in order to contribute to his individual evolution; therefore the Holy Spirit, under the new conditions, must ‘come’ from the risen Christ, in order to free the human being from the objective evolution proceeding from the Father, which is exhausted for the human spirit. Then the human being, too, will be resurrected in his thinking.

In order to elaborate the ‘I’ on the Earth, says Rudolf Steiner, the human being had to receive a decaying body – this is the price of individual evolution. But so long as the human being is ‘involuting’ in his lower ‘I’, he is not able to take into his own hands the activity of nature within him and compensate for the damage inflicted upon it (also in his environment) through his individualization.

As we have already said: The individual ‘I’ is a possession of the hierarchical beings. They acquired it from the Father-principle of the world. The ‘I’ as such is the antagonist of the entire realm of otherness- of-being. For this reason, participants in the Mysteries of antiquity came into possession of the ‘I’ through leaving behind their physical body. In this condition, the Father-principle poured itself into the one undergoing initiation and endowed him with the ‘I’-experience. The Initiates of the Mysteries did not become hierarchical Beings, but nor were they simply human beings. In them were united the earthly and the heavenly nature; whereby the heavenly nature worked into the earthly just as the hierarchical beings work in the development of the physical plane of existence: namely, from above and indirectly.

But in the course of evolution the human being was approaching a condition where he would be able to remain in the physical body, but nevertheless develop an individual ‘I’. In order not to come, in this process, into contradiction with the laws of the universe, it would be necessary for him in the realm of otherness-of-being to take upon himself the work of the Hierarchies on the physical-material world. But because in the human being there first emerges the lower ‘I’ which, although it is a being of Divine nature, is as yet unable to fulfill this task in a higher sense, the realm of otherness-of-being simply rejects it, with the consequence that the world-plan contained within the human corporeality, begins to pass over to the Lord of Matter – Ahriman. The human being is not able, by himself, to resolve these contradictions. For this reason, God Himself came directly to his aid under the conditions of material existence.

Through the Mystery of Golgotha, Rudolf Steiner tells us, it came about that “human souls could now say to themselves, after they had passed through the portal of death: Yes, we have borne it on the Earth, this decaying physical body; to it we owe the possibility of developing a freer ‘I’ within our human nature. But the Christ has, through His in-dwelling in Jesus of Nazareth, healed this physical body, so that it is not harmful to Earth-existence, so that we can look down into Earth-existence with peace of mind, knowing that after the Mystery of Golgotha a wrongful seed is not falling into this Earth-existence through the body which the human being needs for the use of his ‘I’. Thus the Christ went through the Mystery of Golgotha in order to sanctify the human physical body for Earth-existence” (GA 214, 30.7.1922).

Such is the help given by God to man on the path of the development of the ‘I’ in the world of otherness-of-being. But the human being must not receive this help passively, since the ‘I’ and passivity, in their essential nature, are mutually exclusive. For the human being it is not enough for Christ simply to work in him. If he is reliant on the help of Christ, the human being must take a further step independently: like the Initiates of antiquity he must take upon himself the task of rescuing his own body, but in contrast to them he must undertake this entirely within this world. In order not to ‘disturb’ the human being in this work, Christ became invisible, ascended to Heaven and sent the Holy Spirit to help man, who must now, in his ‘I’, ascend to the latter on the path of beholding. In his development of the power of judgment in be- holding, which neither uses the support of the physical body nor has a deadening effect upon it, the human being says to himself, “With the Holy Spirit we will rise again.” This is the true nature of the resurrection in thinking, which is the first step on the path of the coming resurrection of the flesh.

Now that we have seen

more clearly in what the religious-ethical

character of the development of man to freedom

consists, we will consider how it stands in

harmony with the logic of beholding in thinking.

Let us again call to mind the fact that the

seven-membered lemniscate of morphological

thinking is the last, the concluding expression

of the seven-membered evolutionary cycle. The

same laws are at work in both. In the course of

evolution a descent takes place of the higher

spiritual impulses through the stages of the

sevenfoldnesses, each one of which overlies the

next in succession: rounds, globes, root races,

cultural epochs. The last in this sequence is

the sevenfoldness of thinking; in it the higher

impulse begins to free itself from the

otherness-of-being and to reascend: through the

human ‘I’. (For the present the situation is

different, as to the kingdoms of nature.) In the

sevenfoldness of the evolutionary cycle the

activity of the Divine Tri-unity is manifested

in different ways. It is also present in the

sevenfoldness of the thought-cycle. For

clarification see Fig.50. This leads our

research up to the following stage.

The sevenfoldness of ‘beholding in thinking’ is the fruit of the high- est revelation; for this reason God Himself is present within it in His three hypostases. With their help the individual ‘I’ can accomplish the same as that which happens in the sacraments of the Church. The worship of God “in spirit and in truth” does not mean a rejection of sense-reality or the acceptance of truths that come, ready-made, from outside. Christianity is the religion of freedom and not of the renunciation of individuality. It will not be understood “until it pervades all our cognition right down to the realm of physics” (GA 201, 16.5.1920). However, cognition begins with the theory of knowledge, and for this reason Anthroposophical philosophy also begins with it, but in so doing Christianizes it.

The human being can now say: In me is active the Father-Principle. He helped the Initiates attain the individual ‘I’. Now He has confronted me with the luciferized dialectic; but He Himself holds Himself back, behind this dialectic. Though conceptual thinking is lacking in substance, I was nevertheless born within it out of God, as an individuality. Now I see myself faced with two alternatives: Through thinking to die also in the lower ‘I’, as matter is subject to degradation under the influence of its negative force, or to die in Christ. In the latter case I must transform death into a process which gives new life to the corpse of thinking. Then I attain a new consciousness, and I will resurrect with the Holy Spirit – in the higher ‘I’. “The Father is the unbegotten Begetter,” says Rudolf Steiner, “who brings down the Son into the physical world. But at the same time the Father avails Himself of the Holy Spirit to communicate to humanity that the supersensible can be grasped in the spirit, even if this spirit is not directly beheld, but if this spirit works inwardly upon its own abstract spiritual element, raising it up to the living sphere; if it awakens to life the corpse of thinking, through the Christ who dwells within it” (GA 214, 30.7.1922).

In these words of Rudolf Steiner we find a description of the inner, spiritual, Divine side of what we are studying externally, in this world, as the seven-membered cycle, the unity of morphological thinking. In Fig.50 we have represented both sides simultaneously. And we can now say that, as a mirror reflection of the complicated interaction within the Divine Tri-unity, the seven-membered metamorphosis of thinking arises, in which the intellectual element is able, before super-sensible experience arises, to work its way into the living realm of the spirit. The Father Principle is dominant in the dialectical part of the metamorphosis, but (as in evolution) it extends to its conclusion, in that it functions as the foundation of the conceptual principle. The Holy Spirit is dominant in the final, beholding triad of the metamorphosis, but (as in evolution) it extends back to its beginning, expressing itself in the forms of its elements, in the form of the thinking that changes from element to element – i.e. it also works in the connection of the elements as the laws of their metamorphoses. From the very beginning of its evolution the Son is led into the world by the Father. Within the system of the seven aeons the Son acts as the Regent of three of them – of those which play a key part in the becoming of man: those of the Sun, Earth and Venus. Thus, the Christ reveals within the evolutionary cycle the entire fullness of the Divine Tri-unity. This is predominantly His evolutionary cycle. In the thought-cycle this finds its expression in the fact that the Christ-impulse within it directs the second, the fourth and the sixth element, those elements whose nature stands close to the nature of the connections of the elements – i.e. of the laws of metamorphosis. But such are, on the macro-level, the three aeons we have mentioned. Christ reveals to the world the absolute ‘I’. It is dynamic, and is active in all metamorphoses. The elements we have named also form an identity with the working of the thinking ‘I’, which passes from trans- formation to transformation. In the dialectical triad the ‘I’ negates that which has become, by identifying with the antithesis; in beholding (element 4) it tries to negate itself in order to be reborn as higher ‘I’ in the world of intelligible beings, the individualized thought-beings. This is the meaning of the process whereby one works one’s way, through the Christ who lives in man, into living spirituality. All these three elements form a unity in the same measure as the higher ‘I’ is created. As the ‘ur’-phenomenon of this tri-unity there arises within the totality of the seven-membered being of man the triune spirit: Manas, Buddhi and Atma. In the morphological system of thinking it needs to be Christianized. And this comes about when the Manas in the antithesis negates the ‘Fall into sin’ of the idea which is expressed in the thesis that ‘has become’ and remains static. The Buddhi negates, in beholding, the en- tire nerve-sense, material basis of the human subject, a process that can only bear fruit if it takes place according to the principle: We die in Christ. Then the thinking human spirit resurrects, after passing through a series of negations as an intelligible being, and as such it can return, raise itself up, to the Father foundation of the world. Here, Atma begins to work in us: the higher ‘I’ starts to transform our corporeality.

Thus Christ emerges through the thinking activity in His role as sav- iour, as a force which helps the human being to overcome original sin. Rudolf Steiner says: “Whoever beholds the Cross on Golgotha must at the same time behold the Trinity, for Christ reveals in reality, in the whole of his involvement with the development of mankind on Earth, the Trinity” (ibid.). In the thought-cycle this comes to expression in the interwovenness of the said three elements (2, 4 and 6) with the other four. The first two of them are rooted in the manifoldness of the content of the created world (elements 1 and 3); the last two weave the content of the future world of human thought-beings (elements 5 and 7). In the seven-membered nature of man these four elements are rooted in his triune corporeality and the conceptually thinking ‘I’ which arises upon this bodily foundation. The ‘ur’-phenomenon of these four elements can be seen in the Cross of Golgotha. For this is the World-cross on which, according to Plato, the World-soul is crucified, but also the individual, consciously awakened, triune flesh of every human being, which is woven of the elements fire, air, water and earth.

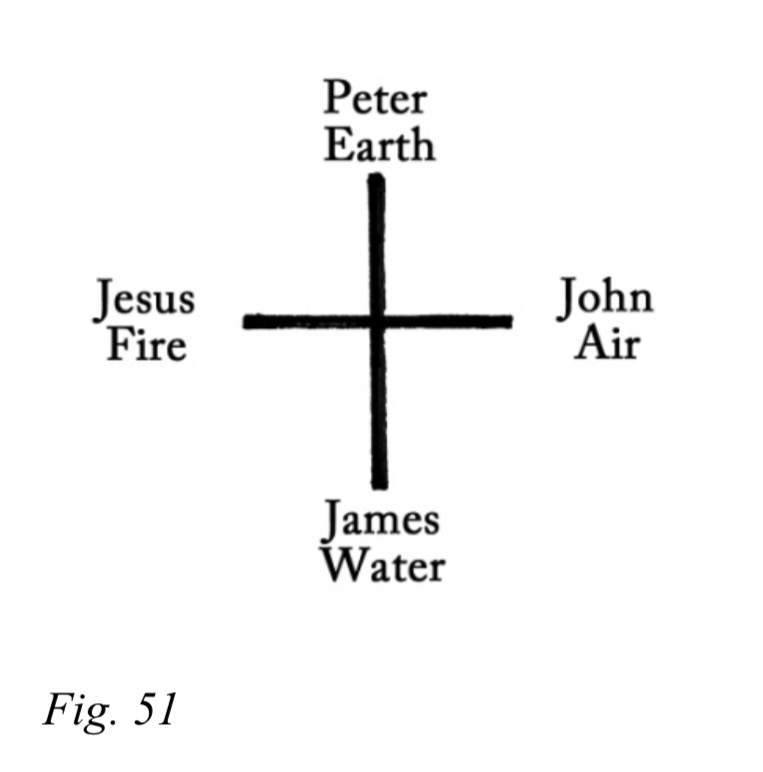

On Mount Tabor, says Rudolf Steiner, this cross

was represented by three Apostles and Jesus

Himself; His element was fire – the element of the ‘I’ (Fig.51).

* * *

Thus we find in the hierarchy of the seven-membered metamor- phoses the evolution of the world unfolding according to the same prin- ciples on both the macro and the microcosmic levels. The outermost limits of these levels – i.e. the boundaries of the manifested universe – are formed by the seven-membered units of the evolutionary cycle and the logic of beholding in thinking. The basis on which they reunite is sevenfold man – a spiritual-organic whole, a system. In it world- development, as regards its principal being, the ‘I’, fell into a state of crisis, which can only be resolved with participation of the human being himself. Help was given to him by God Himself in the form of a special prayer, which is able to imbue his entire seven-membered being with the forces of rebirth, of transfiguration. We refer to the Lord’s Prayer. Rudolf Steiner reveals its esoteric meaning, whereby its effectiveness is considerably enhanced.

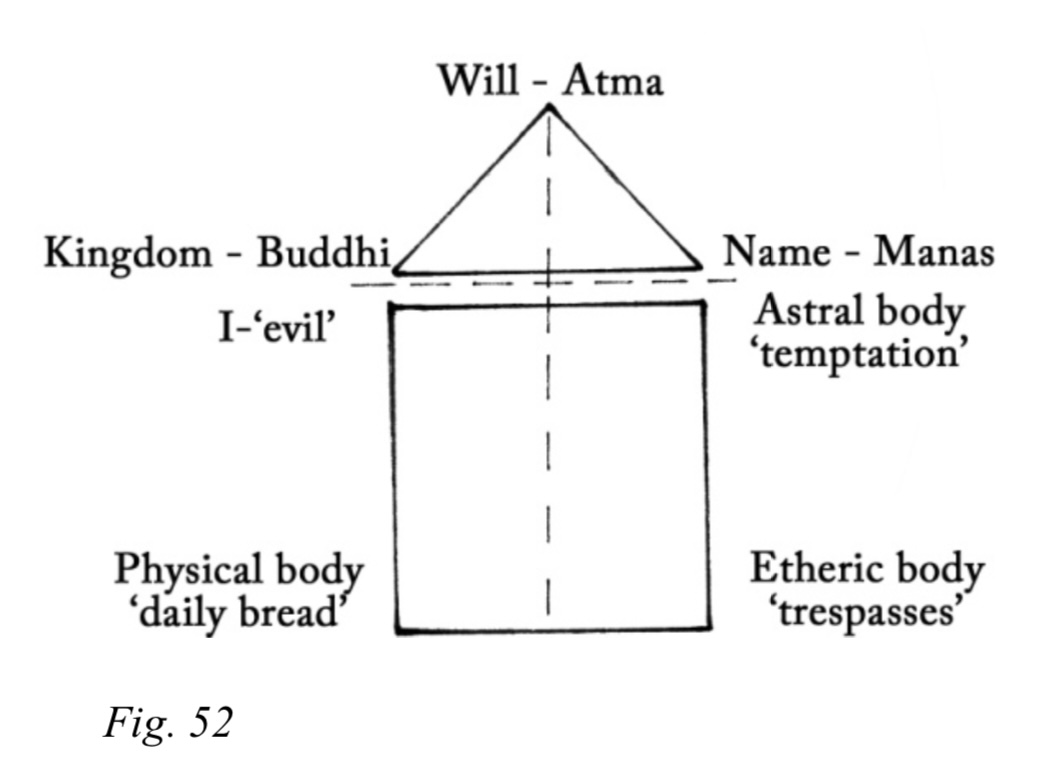

Structurally, the prayer consists of two geometrical figures (God geometrizes!), which have especially deep significance in the esotericism of numbers and symbols.* Both the figures and the elements of the prayer were given by Rudolf Steiner in the form of a diagram, shown here in Fig.52. The concluding words of the prayer contribute to the ascent of the seven-membered being of man into the spheres of the life-conditions (rounds), consciousness-conditions (aeons) and form-conditions (globes): “For Thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory” (see Fig.24) – i.e. to ascent on the stages of evolution (see GA 93a, 27.10.1905).

* They were also known in

the ancient Pythagorean school.

_____

Once we are aware of this, we begin to grasp more deeply why the Lord’s Prayer is the most important prayer and the cornerstone of the most important sacrament of the Church – the Mass, in which the trans- formation of earthly substances and the Communion take place. The triune, higher spirit of man unites the four parts of the Mass, thus bringing about the transfiguration, the spiritualization, the raising onto a higher level of the ‘foursquare’ nature of the human being.

In the course of his earthly incarnation the human being passes through two Mysteries: the Mystery of birth and that of death. Each of these has four parts. The Mystery of birth begins with the descent of the human being from his shared existence in the spirit into the earthly body. Then follows his entry into a relation with matter. The third step is his adaptation to the Earth, to its centripetal forces. Finally the human being acquires the capacity of speech.

Rudolf Steiner tells us that we approach the Mystery of death, the other pole of life, if we follow the ‘reverse’ path, beginning with the gift of speech. For this is also the first part of the Mass: the reading of the Gospel. To this a sermon is sometimes added, which must not be intellectualized, as contradiction (in accordance with the laws of dialectic) will otherwise arise in the listeners. The sermon must contain within it the substance of the genius of language (a supersensible, hierarchical Being).

In the ritual of the Mass a bloodless sacrifice is then offered up – the burning of incense. Thus a counterweight to the centripetal forces of the Earth is created, which helps the human being to adapt to the ‘periphery of the spirit’ – to being within the material world (but also within intellectualism), without becoming totally subjected to it. Here a polar inversion of birth and resurrection takes place. Out of the spiritual centre of the world the human being is born and descends to its material periphery. But in becoming an ‘I’-centre here, he experiences the far spiritual distances of the world (the realm of the spiritual Zodiac, and even what is higher than this) as a kind of sphere which is infinitely remote from him. The offering up of the sacrifice takes place in such a way that the smoke rising with the burning of the incense is imbued with the form of the words that are spoken. Thus the human being contributes to the glory of the world.

In the third part of

the Mass the transformation of matter, its

spiritualization, takes place. What is the force

that brings this about? “....just as the

peripheral forces are working towards the

centre, when we speak of birth, so now, in

offering, the forces which we have already

invoked work outwards (away from us – G.A.B.)

into the universe. They work, because we have

entrusted our word to the smoke. They now work

outwards from the centre and carry the

dematerialized word outwards through the power

of speech itself, and this makes it possible for

us to accomplish the fourth, the opposite of the

descent (to Earth – G.A.B): namely, the union

with the higher, communion” (GA 343, p.178 f.).

Both Mysteries together form a seven-membered unity since they unite within the human being, and he is sevenfold. In addition, they fit into the seven-membered ‘chalice’ of evolution which, for the human being who participates consciously in the sacrament of development, is the Cup of the Grail, which contains within it the host of the Last Supper – the life of Christ Himself. The process described here can also be illustrated by means of a diagram (Fig.53).

The surface, the form

of the Grail Cup (the chalice of the Last

Supper)* is the Divine Glory;

the wine (the water) of the Last Supper

contained within it is the heavenly Kingdom, or

the Life; the oblation is the power of the

heavenly Kingdom, which unites within it the

Life and the Glory. In it holds good the truth:

“I and the Father are one.” As an outcome of the

union of the two Mysteries, the human being

involutes, out of his objective development

which has led him into the ‘darkness’ of the

material world, the spiritual force which raises

him anew into the higher spheres of being. This

brings with it a sanctification of nature, which

is pervaded (as it formerly was) by the spirit,

which descends from the heights. In this process

the human being functions merely as a mediator –

as a priest or a sacrificial priest. The

Christianity of the future with its worship of

God “in spirit and in truth” transforms the

individual human being into both altar and

priest; and the substances to be transformed are

drawn from the soul of man himself. It is not by

chance that the highest activity of the medieval

alchemist-Rosicrucians in their work with the

elements was the reading of the Mass (cf. GA

343, p.122). In the individual cult, which is

oriented towards the future, what serves as an

altar is the etheric centre emerging in the head

region – the ‘etheric heart’, and what serves as

theurgy is the ascent from reflection to the

beholding spirit and to imaginative

consciousness. The realization in practice of a

Christianity of this kind has become possible

for many people since the beginning of the epoch

of the Archangel Michael (from 1879). It means

that one must learn to think, not abstractly,

but in the Trinity, where the Christ acts as the

connecting link between all opposites (see

Fig.50). He, as the Life-spirit incarnate on

Earth, must assume the dominant position in our

triune spirit, He must become the higher law

which calls forth the metamorphosis of the

‘square’ of body and lower ‘I’ with the help of

the ‘triangle’ of the spirit, which is present

in the entire sevenfoldness of thinking. The

apex of this ‘triangle’ must point downwards,

and as it is involved in the dynamic of

development it will, with the progressive

transfiguration of the ‘square’, gradually

assume, under the influence of the higher ‘I’ of

man, a position in which the apex points upwards

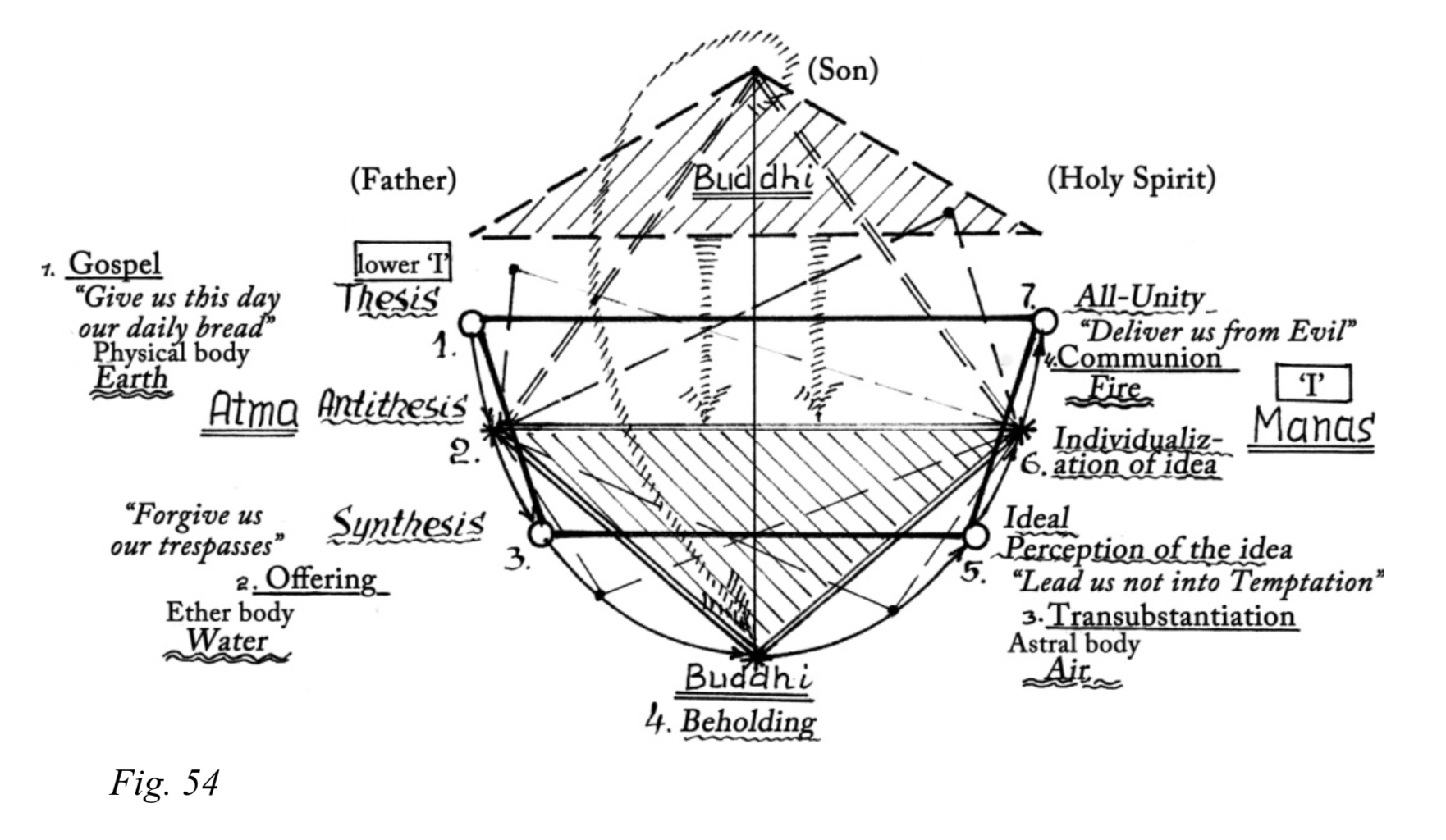

(see Fig.54).

* We recall that this was

the cup of the Last Supper and that Joseph of

Arimathea collected the blood of the Saviour on

Golgotha.

____

As this activity of the spirit in us is the continuation of the objective world-evolutionary process, the structure of seven-membered man undergoes metamorphosis. It assumes a different aspect from that shown in the diagram of Rudolf Steiner’s represented by us in Fig.52. What we see there is the constellation of the creation in relation to the Creator. It is, so one might say, the basic structure from which the process of the development of man proceeds and to which it returns. However, the evolutionary process itself is conditioned by a different position and relation of the Divine Trinity to the creation. This position and this relation are represented in Figs. 26, 27 and 30, and we have already described their process of becoming. In this way the working of the triune spirit in the four constituent members of man and in the sevenfold-nesses of the thought-cycles corresponds fully and completely to the process of world-evolution. Reciprocal relations of this kind have a decidedly religious character. The goal of development, as also of religion, consists in the union of the human being with God. If we can experience the new thinking-process, it is like a Mass which we celebrate within ourselves. The reading of the Gospel corresponds, in such a case, to the setting up of the initial thesis. This we set up as we take our start from the tasks of cognition which is, for us, cognition of the Divine and of ourselves. It is the fruit of our (lower) ‘I’ and, at the same time, the herald of the spirit – the shadowy image of intelligible Being. Then the synthesis can be experienced as the burning of the incense, as the offering. As a judgment it belongs to us, and we strive to integrate it (the synthesis as a phenomenon of the earthly spirit), to ‘think it into’ the world-ether, to free the thinking-process from the physical body, and thus to begin the ‘repayment’ of ‘our debts’, the overcoming of original sin.

As we move on from the third to the fifth element of the thought-cycle, the process of transubstantiation of the lower ‘I’ begins, and the Goethean ‘dying and becoming’ takes place in us. As a result of this process the astral body must be purified and both inner and outer temptations must be overcome, so that pure love for the object of cognition enables us to merge into One with it, and reveals its idea to us in ideal perception. It is at this stage that transubstantiation takes place, the transformation of the entire human being, and the highest fruit of this is the ‘etheric heart’ (see Fig.45). This is actually the Cup of the Grail which we acquire within ourselves. In it we find the Host: the conceptual and moral intuitions referred to in the second part of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. This does not stand in contradiction to our earlier assertion that the etheric heart is an altar of the cult of spiritual thinking. In a cult of this kind the situation is spiritualized to such a degree that that which serves as an altar for the one performing the cult, is at the same time the chalice for the higher gifts of spirit. Someone who does his utmost to receive intuitions cannot, however, force them to appear to him. Rudolf Steiner says: “Whoever knows that the human being allows, with every thought, a Divine stream to flow into him, whoever is conscious of this fact receives, as a consequence, the gifts of higher cognition. Whoever knows that cognition is communion knows also that it.... is symbolized in the Last Supper. ... (one) must make oneself worthy and capable of cognition” (GA 266/1, p.48).

In the process of the new transformation the structure of our thinking begins to resemble the chalice of evolution. And it is worthy of note (as seen in Fig.54) that in such a case it is “sculpted through”, “formed through and through” by the activity of the highest point of the Divine Triangle – i.e. through the activity of the Christ (see also Figs. 26, 27). Such is the working of the ‘Lord’s Prayer’ in the human being if one approaches it in order to serve God “in spirit and in truth”. We find the esoteric structure of this prayer (as represented in Fig.54) different from that given by Rudolf Steiner. The explanation for this is that in the latter case its task is to bring the human being into a relation to the Father of the world who reigns in all Eternity, with his first revelation (Fig.52). For this reason the Divine Manas is, in this structure, brought close to the astral body of man and the lower ‘I’. We, for our part, are considering the prayer within the dynamic of an individual develop- ment in which, not our lower ‘I’, but the I of Christ, the Lord of the Kingdom, transfigures us, beginning with the physical body and abstract thinking, and we are striving with all the forces of our consciousness to draw near to Him.

The Divine Tri-unity works within us as our own higher, tri-une spirit, which we will consciously possess in the future. In the seven-membered cycle of thought it works in the elements of negation, of beholding and of the individualization of the idea: on the axis of our ascent from the lower to the higher ‘I’. This is the triangle of self-creation. When we metamorphose thinking, the Divine Triangle, which was previously supported on our physical body and the higher ‘I’, descends into the depths of our being and begins to rest upon the support of the ether and astral bodies: in the one case (antithesis) according to the principle “I and the Father are one”; and in the other (element 6) according to the principle “I send you the Spirit, the Comforter”. It is in this constellation that the Divine leads us upwards with it into spiritual heights; we begin to worship God “in spirit and in truth”, and this leads us to acquisition of individual Manas – i.e. to the coming into being of the tenth Hierarchy. The metamorphoses of the thinking we have described permeate the human being right through to his organic structures and functions. For, when we free ourselves from thinking in the body, the relation between blue and red blood in it must also change, the relation between breathing and blood circulation. The overcoming of original sin means that the Biblical ‘Tree of Life’ and the ‘Tree of Knowledge’ are reunited within us. And it is, actually, upon these that the triangle of self-transformation is supported in us. But these questions will only be dealt with in the final chapters, as we must first go through the necessary preparation.

The union of the two Trees of Paradise, which separated after the Fall into sin, means that individual consciousness is endowed with genuine being. So far can the logic of beholding in thinking lead us. Its acquisition takes place initially on the conceptual level, but it leads us to higher cognition, which is accompanied by a transformation of soul and spirit, to individual freedom.

At the close of this

chapter we should recall that in the world of

the Great Pralaya the Triune God is revealed as

a fivefoldness (cf. Fig.40), and that the latter

is the higher ‘ur’-phenomenon of the human

being, the macro-anthropos. He it is who, in the

Manvantara, ‘places’ himself as though on two

columns, on the ‘Tree of Life’ (red blood) and

the ‘Tree of Knowledge’ (blue blood). In

cultural history two especially notable

representatives of these two ‘columns’ are

Goethe and Hegel. The spiritual science of

Rudolf Steiner unites them with the help of the

pentagram of the micro-anthropos, who thinks

according to the logic of beholding in thinking.

This in its realization is the religion of the

thinking will, since in this case thinking must

be sanctified, and must become pure will

(Fig.55).

Chapter 3 – Thinking as a Means of gaining Knowledge of the World

Rudolf Steiner characterized the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ in two ways, which are especially important for an understanding of our present study. He said that this book is, in the last resort, “only a kind of musical score, and one must read this score in inner thought-activity” (GA 322, 3.10.1920). In his ‘Outline of Occult Science’ Rudolf Steiner says in the chapter “Knowledge of Higher Worlds” that in works such as the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’ or ‘Outline of a Theory of Knowledge of the Goethean World-View’ we are shown what can be attained by thinking when it “is engaged not with the impressions of the physical, sense-perceptible outer world, but only with itself .... They [these writings] show what thinking can attain when it raises itself above sense- observation, but still avoids entry into the realm of spiritual research. Whoever lets these writings work upon his soul in the fullest sense is already standing within the spiritual world; it is merely that the latter is showing itself to him as a world of thought” (GA 13, p.343f).

It is thus the practice of the path of Initiation that is offered to the reader of these books, and in its character this path has an affinity with creative artistic activity. For this, too, raises itself above sense- observation and, while it remains a phenomenon within this world of appearance, it reveals through itself a supersensible reality. But it can also fail to reveal this. If, for example, a conductor has the score of a symphony before him, he can place a metronome in front of the musicians and tell them to play in strict accordance with its ‘instructions’. The sheets of music in front of them, he adds, show all they need to know about when and with what instruments they need to come in. It is quite obvious that in such a performance of the symphony a work of art can never arise.

The same must be said of work with the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. Even when we have resolved the riddle of its structure and of the character of the thought-movement in it, we gain nothing if we remain bound to the ‘metronome’ of intellectual thinking. Its ‘score’ can only be read by the power of judgment in beholding: this alone leads us into the supersensible before supersensible perceptions begin to arise.

The reality of the intelligible world is opened up to earthly man by way of thinking and also in ethical and aesthetic experiences. If we wish to come into an immediate relation to that world, we must draw together into one all three modes of its manifestation. Only then does thinking become a beholding. The artistic cannot be strictly formalized. On the other hand, it also has certain limits. In connection with what we said about Fig.23 – namely, that the all-determining working of the Divine Trinity comes to expression in the becoming of the world – it can also be said with regard to the work of art that the artist, at the beginning of his creative work, already has a sense of its conclusion, a kind of limit. This is purely aesthetic in nature; it can be extremely far removed from all that is sense-perceptible, and possibly not completely expressible, yet it exists. Every so often it is overcome; it changes and then a new direction arises in art. The poverty of Pop-Art with its ethical and aesthetic relativism bears witness to the truth of what we have described.

The advantages of the logic of beholding in thinking lie in the fact that there are within it formally fixed elements and, at the same time, space for what we would call organized phantasy. This is different in every human being. For this reason we refrain from prescribing, in our structural analysis, a single interpretation as the only possible way of reading the score of the ‘Philosophie der Freiheit’. Our task is to show how it can be read. A work of art is something objective, and the experiencing subject is an integral part of it.

When these preliminary remarks have been taken to heart, we can move on to the third chapter. This is pervaded through and through with the principle of the synthesis. All of its elements press towards the judgment, the assertion. For this reason it will be very difficult to experience in it elements of beholding. But also in the world of nature the objects of beholding behave differently. To behold a plant is one thing, and to behold an animal or a human being is different. Something similar could also be said about the difference between the forms of beholding in the first, second and third chapters. The entire content of the chapter, but its Cycle I in particular, unfolds in the spirit of the final conclusion of the preceding chapter, namely: for us it is important how consciousness lives and experiences itself in everyday existence. As we have mentioned a number of times, however, it is torn apart by the dichotomy between idea and perception. In chapter 3 the attempt is finally made to build a first bridge across the chasm that divides these two, and thus to draw them together to a provisional synthesis. To be- gin with this is done in a very measured way, in beholding, so that the manifest character of certain facts can become apparent to the reader in the way it should. In Cycle I observation appears as the thesis, while the antithesis is reflection upon the object of observation. The initial synthesis seems a rather modest one, but only at a first glance; it is well worth the trouble to ponder it very deeply, and it will show itself to have universal significance: there exist two worlds, one of which the human being himself creates.

CYCLE I

1.

If I observe how one billiard ball, when struck,

transmits its move- ment to another, I do not

and cannot have

any influence whatever

on the course followed by this observed process.

The direction and speed of the second

ball when it comes into

movement is determined by the direction and

speed of the first. So long as my role is

merely that of an

observer I can only say something about the

movement of the second ball when it is already

happening.

2.

The situation is different if I start to reflect

upon the content of my observation. The aim of

my reflection is to

form concepts of the

process. I bring the concept of an elastic ball

into connection with certain other concepts of

mechanics and take into

account the special circumstances which obtain

in the case in question. Thus I try to add

to the process which

takes place with no involvement on my part, a

second process which takes place in the

conceptual sphere. The

second depends on me. This is evident from the

fact that if I do not feel the need I can

rest content with the

observation and refrain altogether from seeking

concepts. If I do feel the need, however,

then I am not satisfied

until I have brought the concepts ‘spherical

body’, ‘movement’, ‘impact’, ‘speed’ etc. into a

connection to which the

observed process stands in a certain relation.

3.

That the observed process takes place

independently of me is beyond all doubt; equally

beyond doubt is the

fact that the

conceptual process cannot take place without my

active involvement.

The element of beholding is sevenfold; it is given in the form of a sub-cycle, which heightens its inner activity. The object of this beholding is man himself. It is essential to accustom oneself to experiencing beholding differently, depending on the nature of its object. Goethe, too, was confronted by this task when, after his study of the plant world, he shifted over to that of the animal world.

In element 4 the activity is not intellectual. It is merely focussed on ‘paring away’ what, at the moment, we do not wish to behold. Thus what we have remaining when we separate the essential from the inessential, or rather, when we look inwardly into this process, is simply the most essential point; this then constitutes element 5.

4.

‡ Whether

this activity of mine is really the expression

of my independent being, ‡ or whether

the

(1.)

modern

physiologists are right, who say that we cannot

think as we wish, but are obliged to

think (2)

according to the

dictates of the thoughts and thought-connections

which happen to be present in our

consciousness

(cf. Ziehen, Leitfaden der physiologischen

Psychologie, Jena 1893, p.171), ‡ will

be

(3)

the subject of a

later discussion.

‡ For the moment we would merely register the

fact that we continually feel compelled to

search

(4)

for

concepts and conceptual connections which stand

in a certain relation to the objects and

processes

that are

given to us without our active involvement. ‡

Whether this is really our

own doing,

or whether.

(5)

it is carried out by

us in accordance with an unbending necessity, is

a question we will leave aside for

the

present. ‡ That it appears, on the surface, to

be our own, is undeniable. We know beyond a

doubt

(6)

that the

concepts belonging to them are not given to us

together with the objects. That I am myself the

active

agent may rest upon an illusion; at all events,

this is how the situation presents itself to

direct

observation.

5.

‡ The question now is this: what do we gain by

finding a conceptual counterpart to a given

process? (7)

The individualizing of the idea leads us back to the thesis and antithesis. Here, they come into ever sharper relief, because the thinking subject takes them into himself and examines them closely. When the thinking ‘I’ unites so actively with the process of observation, their unity also starts to become apparent here, as we see in element 7.

6.

There is a

profound difference between the way in which,

for me, the various parts of a process relate to

one another

before and after the discovery of the

corresponding concepts. Mere observation can

follow the

parts of a

given process as they unfold in time; but until

I have sought the help of concepts their

connection

remains

obscure. I see the first billiard ball moving

towards the second in a certain direction and at

a certain

speed; I

must wait and see what happens after the impact

has taken place, and can still now only follow

it

with my

eyes. Let us assume that, at the moment of

impact, someone prevents me from seeing the area

within

which the process is unfolding, then – as a mere

observer – I have no knowledge of what happens

next. The

situation is different if, before the process is

concealed from me, I have found the concepts

which

correspond

to the constellation of events taking place. In

this case, I can tell what is happening even

when

observation

is no longer possible.

7.

A process or

object that is merely observed reveals, of

itself, nothing about its connection with other

processes

or objects. This connection only becomes

apparent when observation combines with

thinking.

The second Cycle is brief and has a lively dynamic. In chapter 2 we examined in great detail the way the antithesis functions. A reader with an insufficiently acute sense of thought might have the impression that elements 1-2 of Cycle II are simply the continuation of element 7 of Cycle I. But we need only reflect a little longer on these elements and we will feel very distinctly the difference in their character. Elements 1-2 raise Cycle I to an octave and are the new beginning. One could say that they are marked by a new style, if one compares them with element 7 which fully corresponds, as regards style, to all that has laid the ground for it in Cycle I. The dialectical triad of Cycle II recalls the one in Cycle I of chapter I.

CYCLE II

1-2.

Observation and thinking are the two points of